Like many others I had bought the line that it was all about reducing frontal area, but a quick chat with its designer, Derek Gardner, soon set me straight on that. “We found ourselves in a straitjacket. Almost everyone had the same engine, gearbox and tyres; we needed an unfair advantage, and the six-wheeler was it. But it was never about frontal area: that was determined by the width of the rear tyres.”

Instead it was about grip. Four small wheels put more rubber on the road than two conventional wheels; you also gain a greater swept area of brake disc. Better, because a wheel and tyre exposed to a moving flow of air will generate a force at right angles to its cylindrical axis, and the size of that force is directly related to the size of wheel and tyre, so the smaller the wheels the lower that force will be. In short, small wheels meant less lift, which meant more grip. It was pure genius.

The driving forces behind the car were not just Tyrrell and Gardner, but Depailler too. While Scheckter was and remains to this day dismissive of the P34 – he told me he thought the car was rubbish, except his language was a little more colourful than that – it was Depailler, a lover of all things mechanical and experimental, who urged it on. The fact that it was known merely by its project number, rather than as the next in the line of ’00’ racers, demonstrates how unsure Tyrrell was about its viability, and Jenks cites Depailler as the man who provided the ‘real impetus’ to go racing with it.

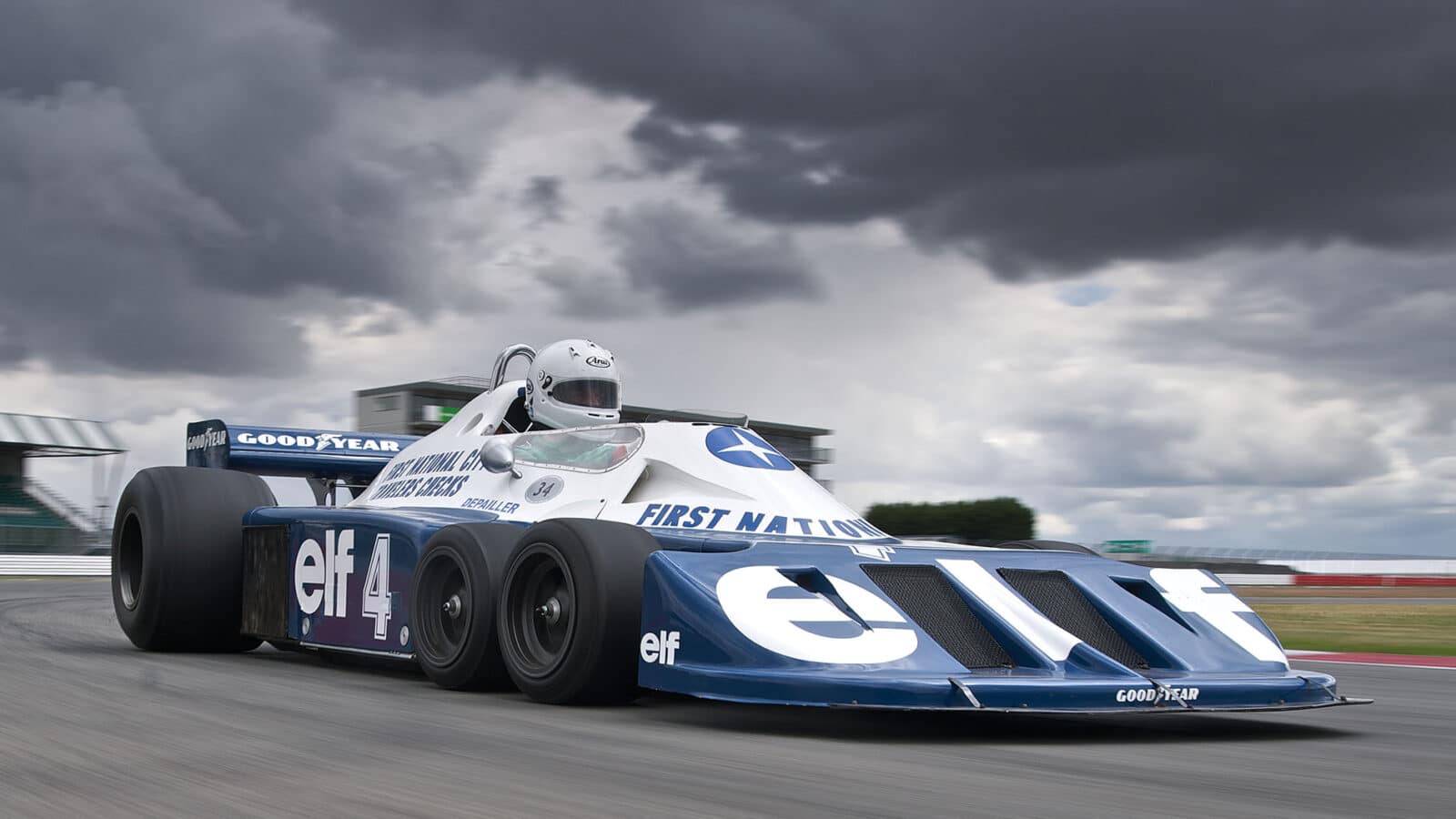

Only P34/2’s tyres were fresh at Silverstone – the rest were as Depailler left it in ’77

Stuart Collins

It’s such a shame Patrick is no longer with us, and not just because his broken Alfa Romeo at Hockenheim deprived the world of a driver who, if greatness was measured by how good a driver was to watch, would have been up there with the best in the world. With his 1977 team-mate Ronnie Peterson gone too, and Scheckter indifferent to the point that it and the dreadful Ferrari 312T5 are the only significant cars from his Formula 1 career which he doesn’t own, there is no one who drove it in anger in period to speak on its behalf.

If you go onto YouTube and look at the on-board footage of Depailler hoofing it around places as diverse as Monaco and the original Kyalami, flinging this very car into extravagant drifts at ludicrous speeds just because he could and, I suspect, because he knew there was a camera on the car, you’ll know man and machine rarely achieved a more harmonious union than this. He once told editor-in-chief Nigel Roebuck: “I run all the time at the limit. I like to run at the limit, to push things as far as I can. I am the same at everything. If I decide to do something, I give it everything. All the time.” See that footage of him and the P34 together and you won’t doubt his word.

But today, some 35 years after it was first unveiled to a disbelieving Jenks on the lawn of Tyrrell’s house in West Clandon, and despite the fact that I still own a rather battered die-cast model bought as a child, it remains a strange beast. It’s sitting in a garage full of other period racing F1 cars, but so far as the attention they’re getting from onlookers relative to the P34 goes, they might as well not have been there. If you hold up your hand and block off the front at the cockpit, it seems conventional, less pretty in its 1977 First National Travelers Checks (sic) livery than simple 1976 Elf blue, but normal enough. But move your hand to obscure the rear and reveal the front and wha you’re looking at might not even be a racing car, but something as likely to be designed to function on the moon, or the seabed. No wonder words failed our intrepid Continental Correspondent all those years ago.

Original Cosworth DFV is on song

Stuart Collins

Those diminutive 10-inch front wheels, the same diameter as those used on a 1959 Mini, are nothing like so interesting as the miniature double wishbone suspension system behind each one and the tiny ventilated discs they carry. I’ve not seen the data but for all they brought in terms of mechanical and aerodynamic grip, the price was paid in mechanical complexity and, surely, unsprung weight.

It’s a surprisingly and, some might say, needlessly spacious car. No modern aerodynamicist would allow such a wide aperture for accommodating a component as easily adaptable as a driver, even if he was the size of Ronnie Peterson. But as someone used to driving such cars in agony, if at all, it’s a blessed relief. We need to remove Patrick’s seat (how strange it is to write that…) but once installed on the bare aluminium tub there’s room aplenty for my shoulders, feet and elbows. Even his now somewhat threadbare belts fit.