Morgan remembers the Penske arriving: “It was the most ambitious rebuild we’ve ever taken on. When it got here it was just the tub and bodywork with some scrap wishbones. There was no engine, no gearbox and no electronics.”

The PC26 is also a fiendishly complex racing car, particularly on the electronics side, with one particularly irksome complication thrown in that would not have troubled its engineers at the time. “Not only do you need 1990s computer software to run it,” says Morgan, “but hardware too.” Put another way, unless you have a mid-90s laptop running Windows 95, it won’t even deign to talk to you. Simply extracting the data recorded and sending it to this magazine so we could publish it took Patrick several hours’ hard work and head-scratching.

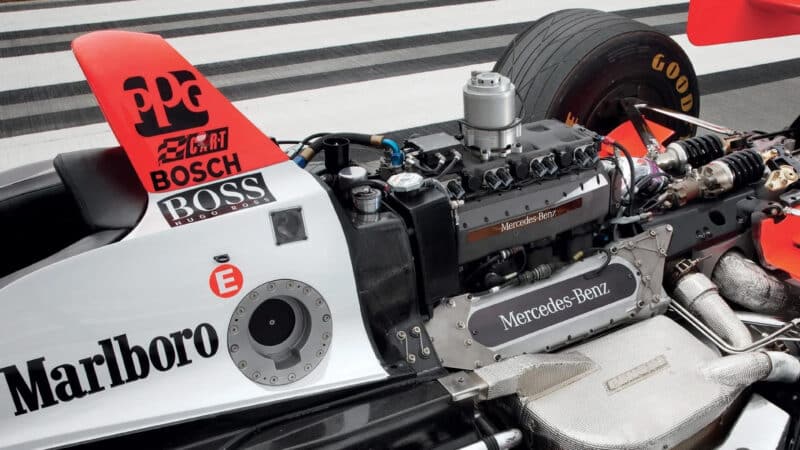

The car was designed by Nigel Bennett for the 1997 season, but was, in fact, the ultimate iteration of an earlier concept. “It really dates back to the PC21 of 1992,” says Nigel Beresford, technical director of Penske Cars at that time. “Nigel [Bennett] is an evolutionary designer, developing one concept over a number of seasons. So just as the PC17-PC20 can be seen as one series of cars, so can the PC21-PC26.”

In fact, while Bennett was the chief designer responsible for the chassis and aerodynamics of the car, as he was going into semi-retirement he had been joined at Penske that year by John Travis, who’d been employed to come up with a clean-sheet design for 1998 but also heavily influenced the design of the PC26’s rear suspension. At first, it seemed Penske had performed a miracle with the car.

Such is the finish of every component, from tiny joints to the carbon tub, that it becomes a thing of pure engineering beauty as well.

Beresford: “We always liked to finish a new car early and have a pre-Christmas test at Phoenix to try and get our heads around its issues. But when we took the PC26 there, Paul Tracy went out in it, went super fast and came back saying, ‘there’s nothing you can do to improve this car – let’s start tyre testing’.”

In fact what was less understood at the time was that while the PC26 was indeed brilliant around short ovals like Phoenix, its talents did not extend to the other types of course on which Champ Cars competed.

“It actually had a very narrow performance envelope and all three of its victories came on short ovals. On superspeedways and road courses, it was nothing like so competitive,” says Beresford. It is possible that these deficiencies could have been addressed, but with Bennett ramping down his involvement and Travis concentrating on the clean-sheet PC27, the PC26 did not perhaps receive the refinement and development attention its raw talent deserved.

Runway is a nod to Cleveland airport circuit

Greg Pajo