Snapshots of Senna

Only a small number of journalists were allowed into Ayrton Senna’s world. Here, one of the favoured few recalls his early friendship – and final falling out – with the great Brazilian

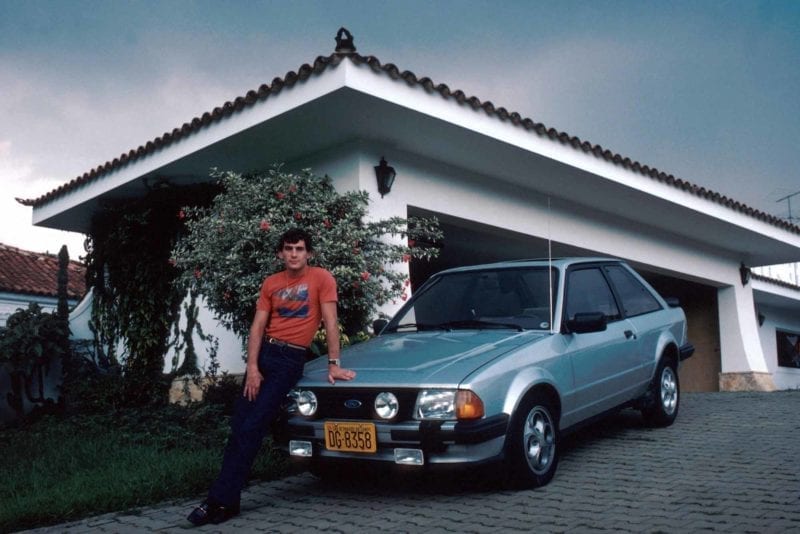

Ayrton Senna outside his family home in Brazil 1984

Motorsport Images

One day, somebody will write a great full-length biography of Ayrton Senna da Silva. Let’s hope it won’t take the couple of centuries for that someone to compile the balanced, well-informed assessment of the Brazilian’s 34-year life that the world had to wait for military heroes like Horatio Nelson. This is not to say that there aren’t already a handful of good or long works on Senna, just that the good ones aren’t long enough and the long ones fail, without exception, to do him justice. The reason for this is that the hacks who knew him best (or at all) are either still too busy writing about current racing or have not yet been able to extract the unvarnished recollections from the Brazilian’s closest associates and family that would be required to do the job properly.

The parallel with Admiral Lord Nelson is perhaps more apt than it first appears, and not just because their deaths convulsed their countries in a way that their achievements in life had never done. Both men combined a passion for improving the technique of their respective professions with an unflinching belief, come what may, that they were right. Along the way, each of them astonished and outraged his contemporaries, making enemies of many. Ultimately, each was openly convinced that he had a date with destiny. Or at least, in Senna’s case, that appears to be the verdict of the biographers who have committed themselves to print since May 1, 1994.

I’m happy to leave the final assessment on Senna to others. Nevertheless, because I had the good fortune to be on reasonably close terms to him during the first four or five years of his career in the big time, I’ve been asked by the editor to write a personal reminiscence. It is a happy coincidence that back in the day I used to carry a camera when reporting on Formula 1 races and events. Having recently turned out some of my old colour slides, memories have been revived of half-remembered encounters. These are they, with illustrations.

I first met Senna when he was racing in F3 with West Surrey Racing, under the care of Dick Bennetts, the canny New Zealander who arrived in England as a mechanic and went on to nurse the careers of numerous future F1 champions. In the year that Senna was racing F3 cars, 1983, I had gone freelance and also got married. With the Macau Grand Prix coming up, and a couple of sponsors’ jobs on offer at the race, it seemed like a great opportunity legitimately to claim part of the cost of our honeymoon from the taxman.

Although this was to be Senna’s last F3 outing, the weekend started inauspiciously. After testing an F1 Brabham at Paul Ricard on the Tuesday before, he’d arrived in Hong Kong thoroughly jet-lagged and headed down to the ferry for the trip over the Pearl estuary to the Portuguese enclave. On Friday, despite a wheel-bending moment on a kerb, he quickly got the measure of the scruffy street circuit and put his Ralt on pole. Knowing that Saturday was a rest day, that night he went on a bender with his team for an ill-advised vodka-drinking contest.

A sporty XR3 was Senna’s mode of transport at home

Motorsport Images

While this was not the first heavy drinking session in which Senna got involved – and it would not be the last – it was certainly the only time he went boozing before a race. He failed to turn up for a couple of sponsor events on Saturday, admitting later that he’d been hungover all day. He was still feeling groggy on Sunday morning, when he did a couple of sighting laps, and disappeared back to the hotel. After a couple of hours’ sleep and a soak in the shower, he was relieved to find that he felt much fresher. Back in his car, he waltzed off with the race.

Having promised a Senna interview to a magazine back in England, I resolved to stick to him on Monday, before he caught the return flight to Europe. Most of the day was spent shopping in Hong Kong (he proved to be a ferocious bargain-hunter) but eventually I got half an hour with him. Being well aware that the image which British people would have of him depended on this piece, he thought hard about most of the questions and (as was his way in interviews) hardly ever looked at me. Although I had been determined in my pursuit of him, I hadn’t been as pushy as a Brazilian journalist would have been. I like to think I made a good impression.

“We flew to São Paulo together, got his Ford Escort XR3 and set off for the family home”

Our next encounter would be in Brazil, only a couple of months later. There was an F1 test scheduled for the Jacarepaguá circuit in Rio de Janeiro, and I was there to cover it for the pioneering magazine Grand Prix International. It was Senna’s first official outing as a Toleman driver, and he was firmly concentrated on that. If I wanted an interview, he scoffed, I would have to wait until after the Rio test and come down to São Paulo. He seemed quite surprised when I agreed. A patient journalist? This was a phenomenon that he hadn’t yet encountered.

After the track had been closed down on Toleman’s first day of testing, I was wandering round the back of the garages when I heard an animated conversation in Italian. It was Senna debriefing with the Pirelli engineers, and from the look of shocked amazement on the face of Pirelli boss Mario Mezzanotte it was clear the new driver had taken charge. It must have been hard for the Pirelli men to absorb the newcomer’s observations about the shortcomings of their tyres, but they were about to learn that he knew what he was talking about.

For his part, Senna wasn’t grandstanding: he was in search of F1 know-how, not show-off lap times. In six days at Jacarepaguá he covered 1600kms without a spin or an engine blow-up. “We were not very quick,” he said, “they have to get the car better. But considering the tyres, for me – a new driver – I think it was good.”

Senna works on his fitness

Motorsport Images

His major preoccupation was his own physical condition. It took only a comparatively short run of 20 or 30 laps to send his head lolling during the Rio test, and with barely eight weeks to go before the F1 circus returned to Brazil for the first race of the new season he had to work hard to get into shape.

Fortunately for me, he had not forgotten the promise of an interview. We flew to São Paulo together, got his Ford Escort XR3 out of the parking lot at Congonhas airport and set off for the family home. I was expecting to have to find myself a hotel room nearby, but after introducing me to his mother Neide (“Dona Zaza”) and his younger brother Leonardo (see previous page), my host said I would sleep in his room while he bunked down with Leonardo. While Senhora Senna da Silva prepared lunch, he showed me round the garage, where he still had several karts and where he kept his collection of radio-controlled model cars and planes.

We spent the afternoon chatting in the living room, not all the time about motor racing and not always with the tape recorder running. He was fascinated that I had actually managed to pick up some Portuguese and was punctilious about making sure I got my vocabulary correct. In return, he was desperately anxious to get his English word-perfect. I remember having to demonstrate the exact (and, when you think about it, very important) pronunciation of ‘can’ and ‘can’t’ – especially when he asked for an explanation of the short ‘a’ used in American English.

He was gratifyingly fascinated by racing history and was astonished to learn that I had actually met Jim Clark, whom he clearly revered. In fact Jim and I had only exchanged a few words while queuing together for sandwiches at an Oulton Park club function on the night before the Gold Cup race in 1965, an F2 event at which I was working as a flag marshal. I was also a Clark fan, although I had seen him crash twice in F1 (at Aintree and Brands Hatch) and again – at my corner, Cascades! – in the ’65 Gold Cup. I put forward my theory that Clark’s weak point was racing in traffic (not a common situation for him) but Senna seemed unwilling to believe that the great Scotsman was anything other than superhuman.

He was also slightly obsessed with a couple of disco hits by the pop singer Gloria Gaynor, which he played at maximum volume on the car’s cassette system. He obviously liked discos because that night, while I set about my various deadlines, he put on a smart shirt and headed off somewhere for an evening’s dancing. I woke up when he returned. It was past three o’clock.

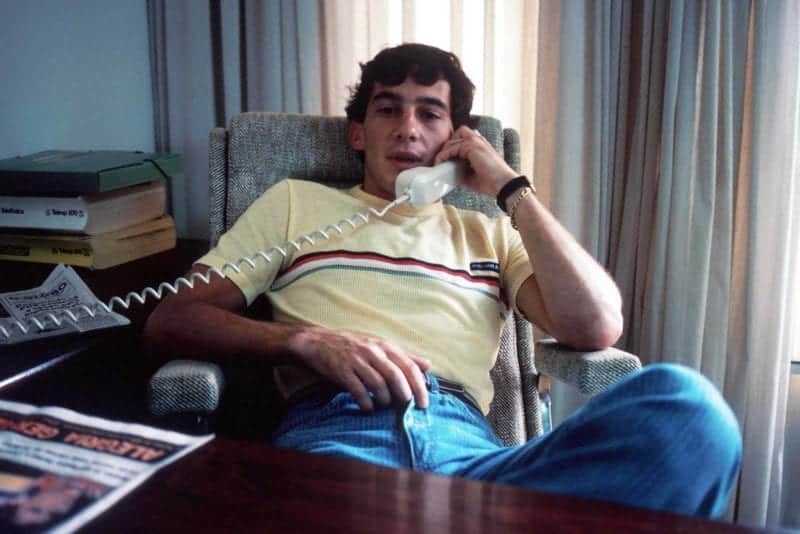

Senna makes a business call

Motorsport Images

The following morning, Senna was determined to get down to his training programme. He’d been in touch with the manager of the national volleyball team, who had created a series of exercises which he practised by the side of the family pool. It didn’t look particularly strenuous to me, but he also swam dozens of lengths. This gave me a chance to get to work with my Canon, some of the results of which are published here. Sorry about the distortion. Having discovered that a wide-angle lens is super-tolerant of poor focusing, I was using a cheap but effective 20mm…

Although the Senna home was spacious and luxurious, it was located in what appeared to be a fairly rough neighbourhood. Security was guaranteed by high walls topped with broken glass, and there was a ferocious guard dog. I got the impression that the family was proud of its humble origins (Senna’s grandfather had been a chauffeur) and had no ambitions to move somewhere more glamorous.

“He asked me to write down the words of Gloria Gaynor’s I Will Survive song and let him have the transcript”

In the afternoon, as I packed my bag, he refused to let me get a taxi and insisted on driving me to the airport. On the way, he asked me to write down the words of a Gloria Gaynor song and let him have the transcript. I have to confess that I never did so. The song was I Will Survive.

It would be a couple of years before Senna started to take physical training as seriously as he should have done, and there were several races in his first year, 1984, when exhaustion intervened and he only just managed to struggle to the finish. But his unending search to improve himself prompted him to tackle a sports car race. The invitation came through his friend Domingos Piedade, the well-connected Portuguese businessman who was running Reinhold Joest’s team of Porsche 956s. It was an opportunity to learn the recently opened new Nürburgring, and in mixed conditions the crew of Pescarolo/Johansson/Senna finished the 1000km race in eighth.

Soon afterwards, Piedade told me that Senna had promised to give his impressions of the car, but had been unable to do so immediately after the race. In the absence of a mobile phone, he recorded everything, in Portuguese, on a tape recorder while driving in England and later mailed the tape to his friend. It now seems that he had been driving to Hethel, where he had started the secret negotiations with Lotus for 1985 which would get him into legal hot water with Toleman.

Lunch is served by mother Neide

Motorsport Images

Piedade said the taped debrief had taken at least an hour. Senna not only remembered every little feature of the car’s engine and handling but also offered tips on how to make it easier for the driver. “When I told Joest,” Piedade recalled, “he got so excited that he demanded to know when he could get Senna back in one of his cars. I told him there was no question of Senna ever driving a sports car again.

“What I had to explain to him was that Senna hadn’t driven the 956 for the team’s benefit, but for his own. He was looking for a new experience and he’d found it. But it was a one-off and Reinhold should count himself lucky to have had Senna in one of his cars.”

The scene, in May 1986, was the neatly groomed pitch in front of the Esher Cricket Club’s pavilion, where Ayrton Senna was devoting himself to the one passion outside racing to which he was willing to admit. He fired up the engine of a model helicopter and prepared to fly it off the greensward via eight channels of radio operated from the console beside him. He’d never flown the thing before, but after only one hard landing he mastered the technique.

Beside him was his best friend outside his family, Maurício Gugelmin. They met when they were both racing karts in Brazil. Gugelmin had a truck with enough room to carry Senna’s karts, too. They buddied up and never had a hard word. Needless to say, they were racing in different categories.

Gugelmin, four years younger than Senna, followed his friend to England and had encouraging successes in the lower formulae, including a win at Macau. With Gugelmin’s pretty wife Stella they shared homes in Norfolk and Reading. Now they all lived in a comfortable suburban house on an exclusive estate just around the corner, which Senna’s first year at Lotus helped to buy. It turned out to be a perfect arrangement, allowing a homely Brazilian atmosphere and the opportunity for each to bounce ideas and projects off the other.

Gugelmin held Senna’s driving ability in an awe which is unknown between people who have to consider themselves the best. He told of a Formula Ford 2000 race at Snetterton in 1982 when someone spun in front of his friend on the first lap. Senna was forced to drive over a kerb, which flattened a brake pipe. In spite of the total lack of brakes he won the race, overtaking several good men on the way.

Senna masters a radio-controlled helicopter at Esher Cricket Club – next to racing, model planes and cars were his passion

Motorsport Images

“When Ayrton came into the pits he was waving at me frantically to get out of the way because he couldn’t stop,” remembered Gugelmin. “I checked the front brake discs and they were cold. He really had no brakes…”

Gugelmin was a capable, dedicated driver who went on to contest 74 F1 races over five years. He only ever got onto the podium once and subsequently lowered his sights to race in America. His closeness to Senna enabled him to provide me with insights that I would not otherwise have had, and it was to him I turned when Brazilian newspapers started to raise questions about Senna’s sexuality.

Gugelmin said that his friend was actively heterosexual. He went further, recounting the story of how, when one of Senna’s girlfriends had fallen pregnant, he had been asked to help out. Senna had agreed to pay for the woman to have a termination but he had been too busy to accompany her to the clinic. He had therefore called Gugelmin to drive her there.

As Gugelmin rather disapprovingly noted, while the incident left nothing to doubt about Senna’s sexuality, it strongly suggested that his on-track ruthlessness sometimes overflowed into his ‘civilian’ life.

Monte Carlo, July 1988. The Houston Palace was a new residential building on the smart eastern side of town, one of the many concrete boxes which sprang up in the Principality to accommodate the wealthy new European classes – sportsmen, entertainers, arms dealers and suchlike – who craved the virtual taxation immunity which Prince Rainier could offer in his pocket handkerchief fiefdom. Senna rented an apartment on the ninth floor.

I was here for a rather prosaic reason. A week earlier, I’d arranged to interview Senna at a test that took place at Paul Ricard. Arriving at the circuit mid-morning, I had commandeered a chair and sat waiting for him to find a moment. Between runs, he greeted me with a handshake. But as the day wore on he became immersed in his thoughts.

When the track was closed for the day, I expected my moment had come. Senna packed up his things, snapped his briefcase shut and turned to me. “Did you come here for anything?” he asked. He had, of course, completely forgotten our interview – and I should have guessed as much hours before.

He had another appointment, he explained. Since I was already in France for the forthcoming French GP, he generously offered to reschedule our appointment for the day after the race. This was perhaps fortunate, because I learned over the weekend that he had been quoted in the Brazilian press about his spiritual beliefs.

Two months earlier, Senna had crashed out of the Monaco GP while leading by half a minute. He had immediately walked out of the circuit and headed for the Houston, barely 200 yards away from Portier, the corner where he had crashed. Sitting here at home on the sofa, he was telling me that he crashed because he had slowed down and lost concentration.

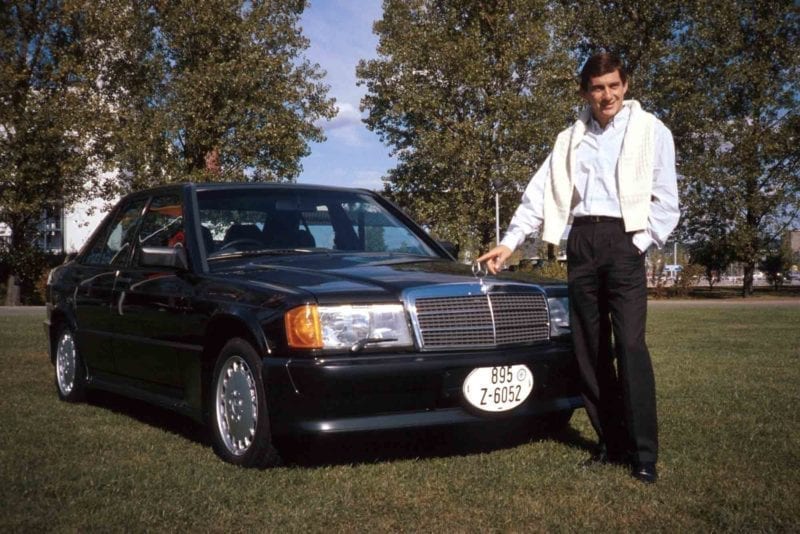

The Brazilian poses with an upgrade on his Ford Escort

Motorsport Images

The TV had caught the moment when he got out of the McLaren and removed his balaclava. No emotion at all on that impassive, finely-chiselled face. “There was nothing to gain and nothing to lose from going apeshit,” he said. He didn’t even call up his pitcrew on the radio. Just turned on his heel and left.

I knew, though, that his explanation did not match with facts from the team, especially his claim to have slowed down. Was it possible, I asked, that there was a spiritual element to the crash? Had a higher power intervened?

Without looking at me, he just said, “F*** off, Mike.”

One year later, with his first world title in the bag, Senna told a different story in an extensive interview with the Brazilian edition of Playboy magazine. At Monaco, he admitted, he had been in a sort of trance. Coming down to Portier he had seen a light shining from out in the sea, which he interpreted as a divine command to sacrifice his race.

“It was chilling – he would not talk to me”

He went further. At Suzuka, where he won the title, he had seen a vision of Christ as he went round the Spoon Curve on his victory lap. The figure (“dressed in ordinary clothes”) had slowly risen to the heavens as he passed.

I subsequently wrote a piece about these revelations which displeased him. It is my belief that while a man’s faith should guide him in his daily life, there is no place in sport for God-botherers. We choose to compete in sports (I wrote) for any number of reasons, most of which are entirely selfish. One of the basic precepts of Christianity, I had been taught, is that God loves all men equally. It is therefore hypocritical and irreligious to ask Him to favour anyone – especially oneself – in a sporting contest.

From this point onwards, Senna made it clear that I was no longer on the list of his favoured journalists. It was a chilling experience. Nobody at McLaren could tell me what had stirred his anger and he was not prepared to talk to me.

It was at least two years before I had a chance to confront him privately. It happened in Hungary, where we were booked into the same hotel, and one evening we found ourselves in the same lift. When he stepped out, I followed him. He knew it was me, but only when he got to his room would he acknowledge my presence.

I asked him politely what it was that I had done wrong. A look of resignation came over his face. “It’s very complicated, Mike, and I’m not prepared to discuss it now,” he said.

Was there no way we could resume the friendly relations we’d had? “No,” he said. “Never.”

That was the last private conversation I would ever have with him.

Senna in the McLaren colours he was synonymous with

Motorsport Images

DSJ on…

A remarkable race to pole at the 1990 Italian Grand Prix

During Saturday morning practice Senna had barely set off from the pits when his engine telemetry told the Honda engineers that all was not well. He was instantly back and as the trouble was not of a simple nature the decision was taken to change the engine.

The spare McLaren was for the priority use of Berger for this meeting, only available to Senna in an emergency, so it was prepared for the Austrian’s size and driving style. Before Senna could use it many things had to be changed, so while one group of mechanics was taking the engine out of Senna’s car another was altering the spare.

Final qualifying began at 1pm. Senna’s race car was still being finished off and the Brazilian was standing at the back of the workshop calm and composed. Just before the Ferraris went out Senna’s car was finished and he did one quiet warming-up lap and returned to the pits for minor adjustments.

Prost, at his brilliant best, did a lap in 1min 22.935sec to claim pole by mere hundredths of a second. Senna went out for another ‘test’ lap, returning to the pits without completing a timed lap, and sat waiting, confident all was well. Less than four minutes before the session ended his McLaren trickled quietly down the pitlane. As he began his flying lap the chequered was being unfurled. Next time Senna went across the line the timer stopped at 1min 22.333sec and an air of incredulity wafted up and down the pitlane.

Not only had Senna snatched pole back with seconds to spare, he had done so by nearly half a second, and with only one flying lap for the whole session. But what a lap! Personally I could have packed my bag there and then and returned home, for anything else was going to be an anti-climax…

The Italian GP gave Senna his first win at Monza, his 26th GP victory, his 49th pole position and he set a new lap record and race record for the present-day circuit and led from start to finish. Not a bad weekend’s work in spite of a certain amount of trouble.