He’d married American actress Louise King after a whirlwind romance early in 1957. She was older and divorced and his parents didn’t approve. Neither did Enzo Ferrari. Friends recall the pair being very much in love. Ferrari painted a different picture, one that probably said more about Enzo than Peter.

After Dino’s passing in 1956, Ferrari’s paternal attitude towards Collins was stronger than ever. He even gave him Dino’s former apartment so he could live near the factory and would often visit him. Mrs Ferrari even used to do his laundry. When Collins married and the small apartment was no longer appropriate, the old man lent the couple one of his villas. He was displeased when they moved out to go and live on a yacht in Monte Carlo.

Enzo’s take was as follows: “He still persevered with his old enthusiasm and skill, was still outstanding, but a change nevertheless became evident in his happy character. He became irritable. Friends whispered that America had robbed him of his sleep. My last memory of him is when I shook his hand before he left for the Nürburgring; looking at him, I was suddenly seized by a strange feeling of infinite sadness. As I went back to my office I could not help wondering if it was some sort of presentiment.”

At the ’Ring the 26-year-old made a fatal error while trying to stay in touch with Tony Brooks’s race-leading Vanwall. Was he pushing himself as he never used to do, determined to prove an old man wrong? MH

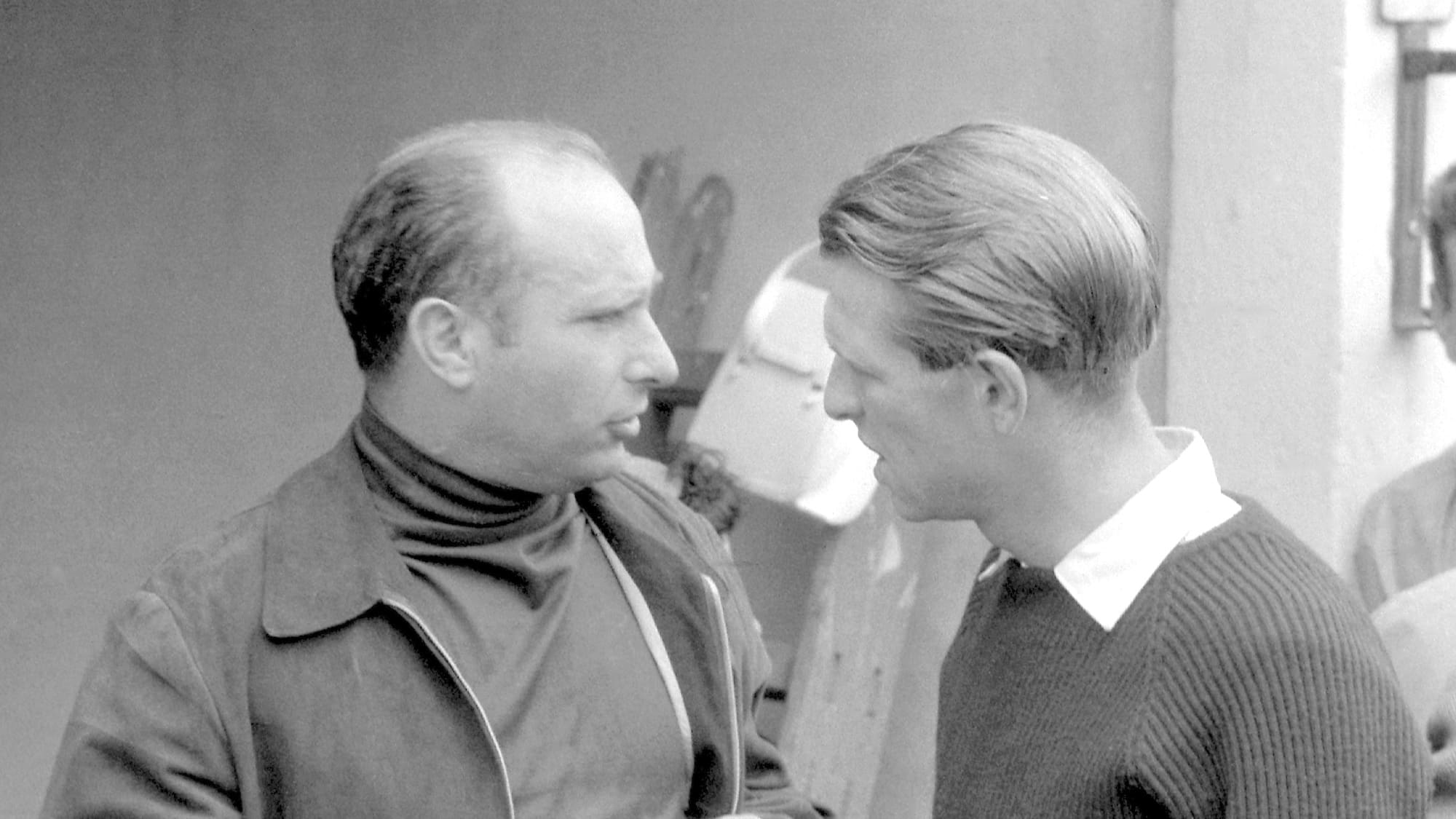

Collins at the Nurburgring for the 1958 German Grand Prix

Grand Prix Photo

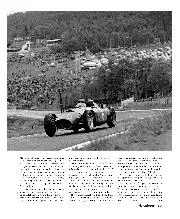

I remember the period when young British drivers would race go-karts or 500cc racing cars for fun, and some would become sufficiently proficient to be offered contracts with F1 teams. Such was the case with Peter Collins. He was a close friend of a similarly inspired and competent young man named Mike Hawthorn. The lively disposition of them both, and Mike’s pranks and practical jokes, certainly made a notable feature of racing in those days.

Both had the advantage of fathers who owned motor businesses, Collins’s in Kidderminster, Hawthorn’s in Mexborough until Leslie Hawthorn moved to Farnham in Surrey and opened the TT Garage there. It was then that I got to know them both, being allowed to drive the TT Alfa Romeo, and I persuaded my wife to present Mike with the Brooklands Memorial Trophy for his Goodwood results in his father’s Riley. Hence my special interest in the later race achievements of both these talented drivers.

Peter Collins came up the harder way, perhaps, in starting with a F3 500cc Cooper-Norton at the age of 17 in 1949. Mike Hawthorn began a year later, aged 21, with the two Rileys prepared at the TT Garage.

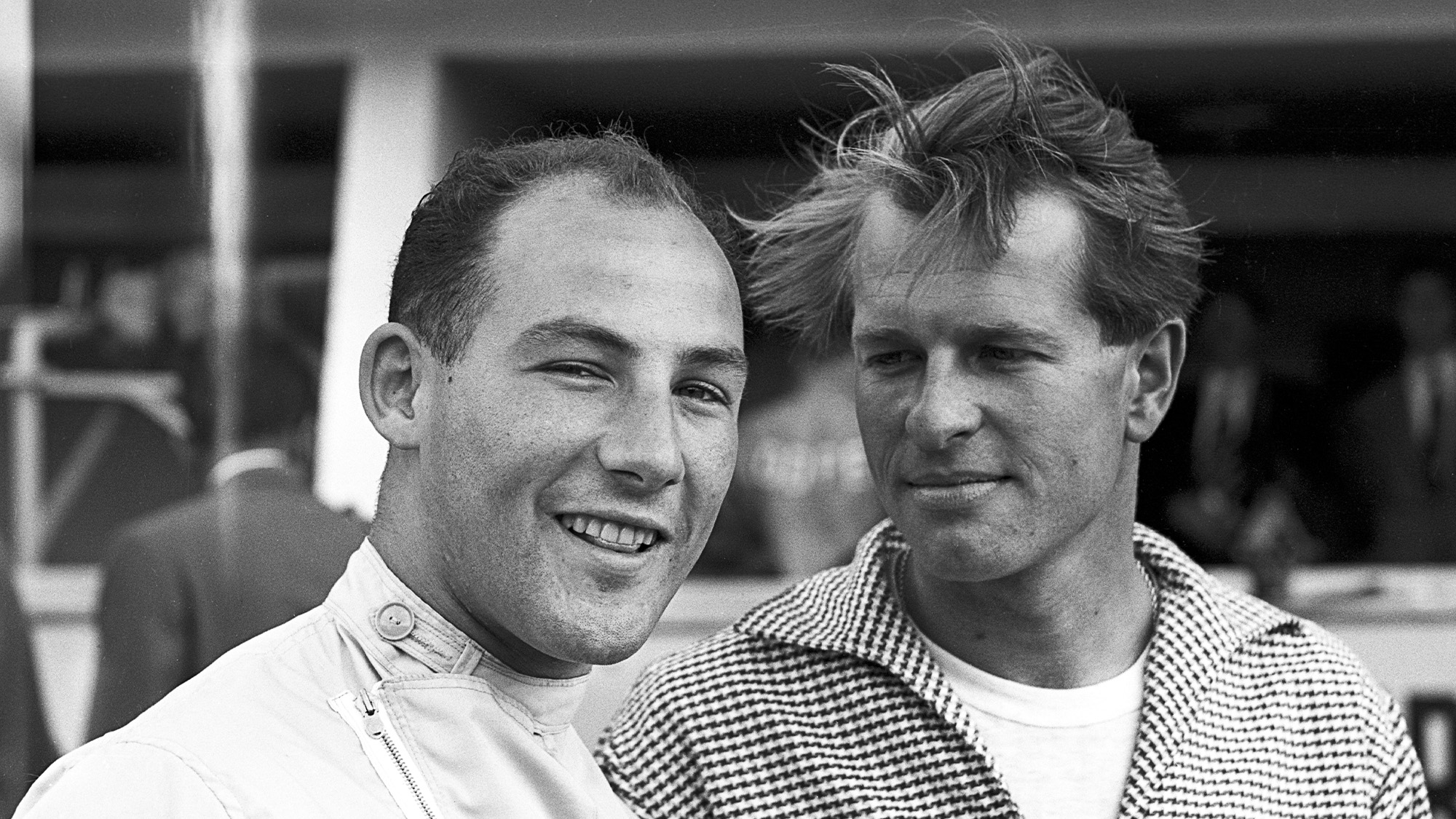

Collins shared an Aston with Moss at Le Mans, ’56, finishing second

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Peter scored immediate successes. He won at Goodwood and in a 100-mile Silverstone race in 1949, and was driving a Cooper-JAP in 1950 hillclimbs. Teaming up with Frank Aitken, Alf Bottoms and R Dryden, Collins then raced the JBS-Nortons, until 1951 when Bottoms and Dryden were killed. Peter then changed from 500cc-class to competing with John Heath’s F2 HWMs; Stirling Moss and Lance Macklin were also involved. Collins then bought a JTX Cadillac-Allard which he entered for the 1951 Dundrod TT, but the diff broke.

By 1952 Collins was the winner (with Pat Griffiths) of the News of the World BARC Goodwood Nine-Hours sports car race – the first British night race – having been signed up by John Wyer on Reg Parnell’s advice to drive for the official Aston Martin team. The two young drivers fully justified this, averaging 75.42mph, covering two and five laps more than the two Ferraris which were second and third.

In the 1952 Belgian Grand Prix at Spa, Collins drove the No. 52 Alta-engined HWM but retired when a driveshaft broke. He finished sixth in the French GP at Rouen but in the British GP at Silverstone his HWM retired with engine trouble. In the German GP at the Nürburgring, the crankshaft broke before the race and he was a non-starter. In 1953 Collins’s only races for the HWM company were in the Belgian GP at Spa, where clutch failure resulted in retirement, and at the British GP at Silverstone when an accident eliminated him.