As a concept it was brilliant and one that, in reality, had some interesting and positive by-products. These included massively reduced brake pad wear and, thanks to the vastly higher speeds at which the front wheels turned, much better brake cooling too.

At first, all went splendidly. Gaining the bespoke components needed for the P34 (suspension, brakes, shock absorbers) was easy enough and Gardner was amazed by just how eager Goodyear was to develop and supply the tiny 10-inch front tyres. Developing the car, however, took an age.

“When we first announced the car,” Gardner remembers, “it was the end of 1975, it hadn’t turned a wheel and, while we had confidence in it, we told everyone it was a concept for research purposes which might or might not have racing applications.”

The problems, some of which were more perceived than real, were these. First, the driver could not see the front tyres which at first made Gardner sufficiently worried about the P34 pilots being able to place the car accurately in the corners that he cut portholes into the bodywork; this way a driver could also keep an eye on tyre condition. In fact, the portholes soon became covered in dirt and the drivers, once used to the car, never had trouble aiming it into the apex.

Scheckter described the P34 as “rubbish”

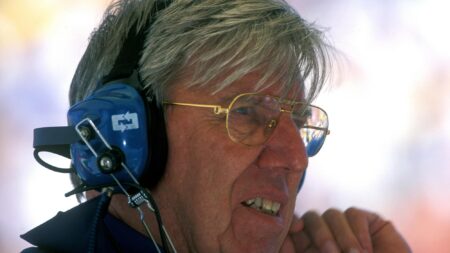

Grand Prix Photo

A more thorny issue was brake balance, since it not only had to be achieved between the front and rear, but also between the four front wheels. If one axle locked before the other, it would have the effect of either shortening or lengthening the wheelbase. This would, of course, introduce rather unwelcome characteristics into the handling. Scheckter, despite winning the 1976 Swedish GP in it, is scathing about the P34. “It was a rubbish car. I never agreed with the two fundamental concepts behind it, reducing frontal area and improving braking. Frontal area is determined by the rear tyres, and as for the brakes, as soon as one set locked you had to lift off. It only really worked on very smooth surfaces and, back then, there just weren’t many of those around.”

Even so, as the winter drew on and ’75 turned to ’76, it did become abundantly clear that the Project 34 was nothing if not swift. The team tested almost non-stop, not simply ironing the bugs out of the six-wheeler but also doing comparative tests against its still-extant predecessor, the 007. “And soon,” Gardner says, “on any circuit and with either driver, the P34 was quicker.”

To an extent it would have been rather concerning had it not been. The 007 had made its debut in 1974 and while it had proved itself more than capable then — Jody and Patrick came first and second in Sweden just as they would two years later — the game had rather moved on. Even so, the 1976 season would be already four races old before the concept became reality at the Spanish Grand Prix. In the heat of Jarama, a lone P34 was provided for Depailler who duly qualified it ahead of everyone save Hunt and Lauda. The 007-borne Scheckter could manage just 14th.