The new car, the Vanwall Special, made its debut driven by Alan Brown at Silverstone on May 15, 1954; the inexperienced driver managed fifth fastest in practice and sixth in the first heat, but retired in the final with a broken oil pipe. The next stage was to increase the capacity of the new engine to an interim 2.3-litres. The car appeared next in July at the British GP with Peter Collins at the wheel. Eleventh on the grid was promising, but a gasket blew on lap 16. Another outing at the Italian GP, the last at this capacity, produced an excellent seventh for Collins; better still, he beat the entire Maserati 250F field home.

As a shake-down, 1954 had been instructive. Clearly, there were teething troubles with many of the 2 1/2-litre machines, even the Mercedes at times, but the car had, by and large, become reasonably competitive (at least with the non-Mercedes cars) and so Vandervell decided that 1955 would be the year when he went motor racing properly. The car was no longer a slightly apologetic Vanwall Special, but simply a Vanwall.

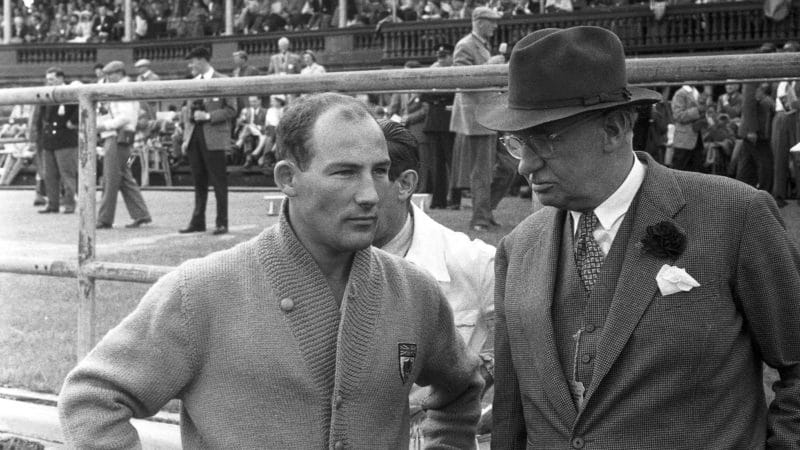

The surreptitious introduction of the marque paid dividends in PR terms; there were no massive public expectations of this merely promising car, as Vandervell had avoided the trap which Raymond Mays had devised for himself and BRM, so development could go ahead logically and at its own pace. Despite the attempts of the fourth estate to conjure up a huge rivalry between BRM’s Alfred Owen and Vandervell, the truth was rather different. Owen was as unlike Vandervell as a man could be; he was patient to the point of saintliness, modest in his private life, and tolerant of others. He was neither profane nor vulgar and there was not an ounce of side in his personality. He respected Vandervell’s flair at risk-taking and, reciprocally, Vandervell thought well of him. As John Cooper put it: “At one end of the paddock would be old Vandervell dispensing caviar and champagne to all his friends from his vast caravan, with the Thin Wall Special looking proud and defiant, and at the other end of the paddock would be Alfred Owen with his BRMs and a packet of sandwiches.”

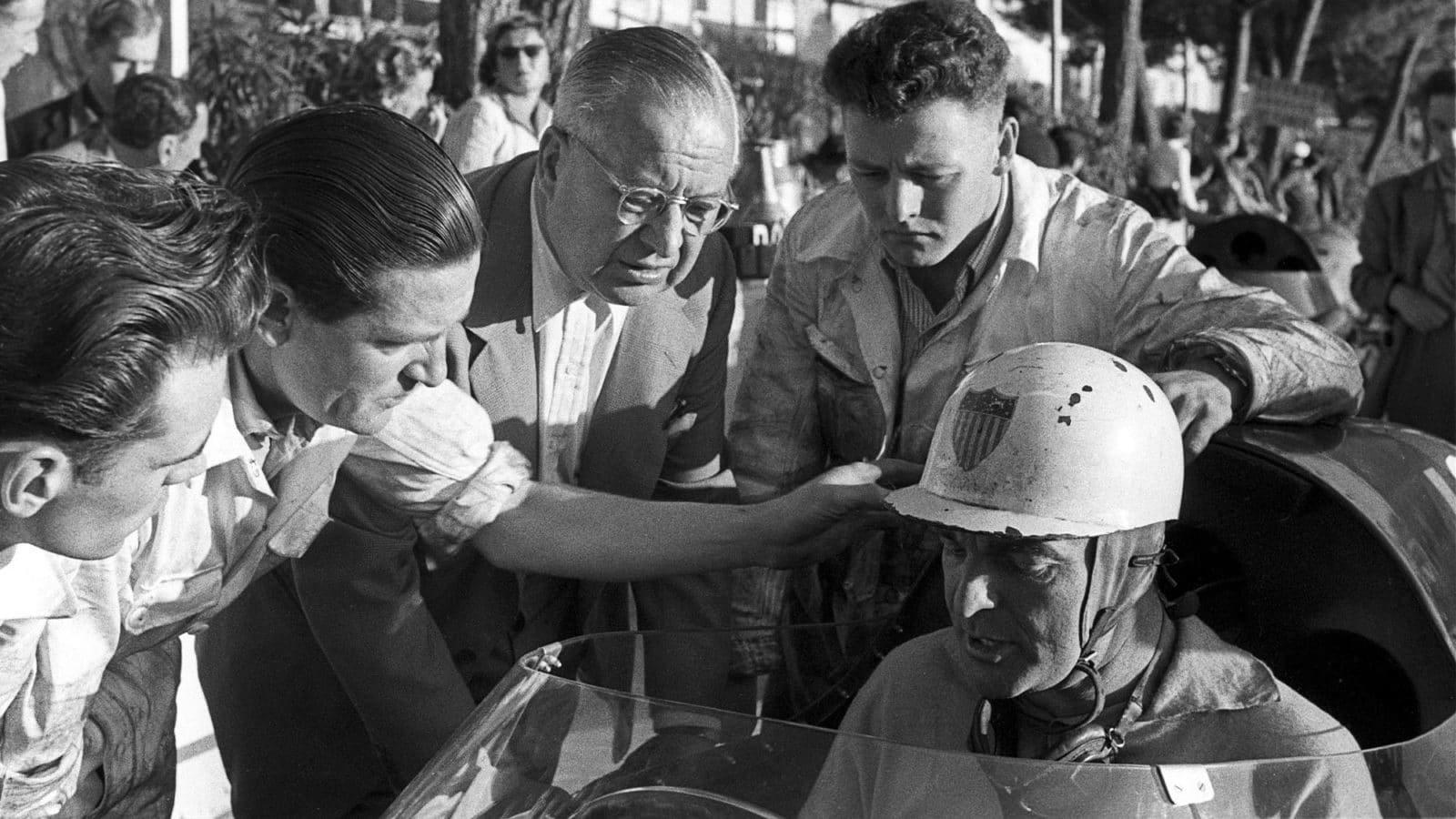

Mike Hawthorn driving for Vanwall in the 1955 Monaco GP – he would soon be back at Ferrari

Getty Images

So, 1955 would be the start of a serious and (crucially) public effort; no longer was there room to be casually disingenuous for whatever reason. As a driver commits to a difficult corner so Vandervell was now committing to Formula 1. Every gruff utterance, every dismissive shrug, every bitten-back profanity at embarrassing failure would henceforth be public property and therefore subject to endless speculation and dissection by both the informed and uninformed alike. It would be hard work and on many levels…

Vandervell was 56 now; he had not yet reached that age, whenever it is, after which a man starts to look into his past rather than his future and, perhaps bolstered by the experience of Enzo Ferrari, for whom he had a profound respect, even though it was roughened by acquaintance, he buckled to.

One of the most troubled years in the history of any sport was to be another shakedown period for the Vanwall team; for in 1955 there was no serious hope of anyone actually beating the awesome Mercedes factory effort. One man who might come close was Mike Hawthorn, who, amid much media attention, was signed in January. To support him, Vandervell hired Ken Wharton, who had struggled manfully with the V16 BRM.

“Vandervell had already wrecked the clutch driving the car to the circuit – Hawthorn was not impressed”

The season did not start well. May’s International Trophy at Silventone saw Hawthorn retire on lap 15 and Wharton crash on lap 23; the car caught fire and Wharton’s burns put him out of racing for two months. At Monaco, Hawthorn, the sole entry, retired with a broken throttle linkage. At Spa in June, Hawthorn retired again, but Vandervell, exercising his customary droit de seigneur, had already wrecked the clutch when driving the car to the circuit which had impressed Hawthorn not at all, and while drowning his sorrows after the race he rather impulsively quit the team. He was back on Ferrari’s F1 books within the week.

He was replaced by Harry Schell who, while not a driver of the calibre of Hawthorn, threw himself into the task with typical enthusiasm. Schell was to win four races that year, sadly none of them a championship event.