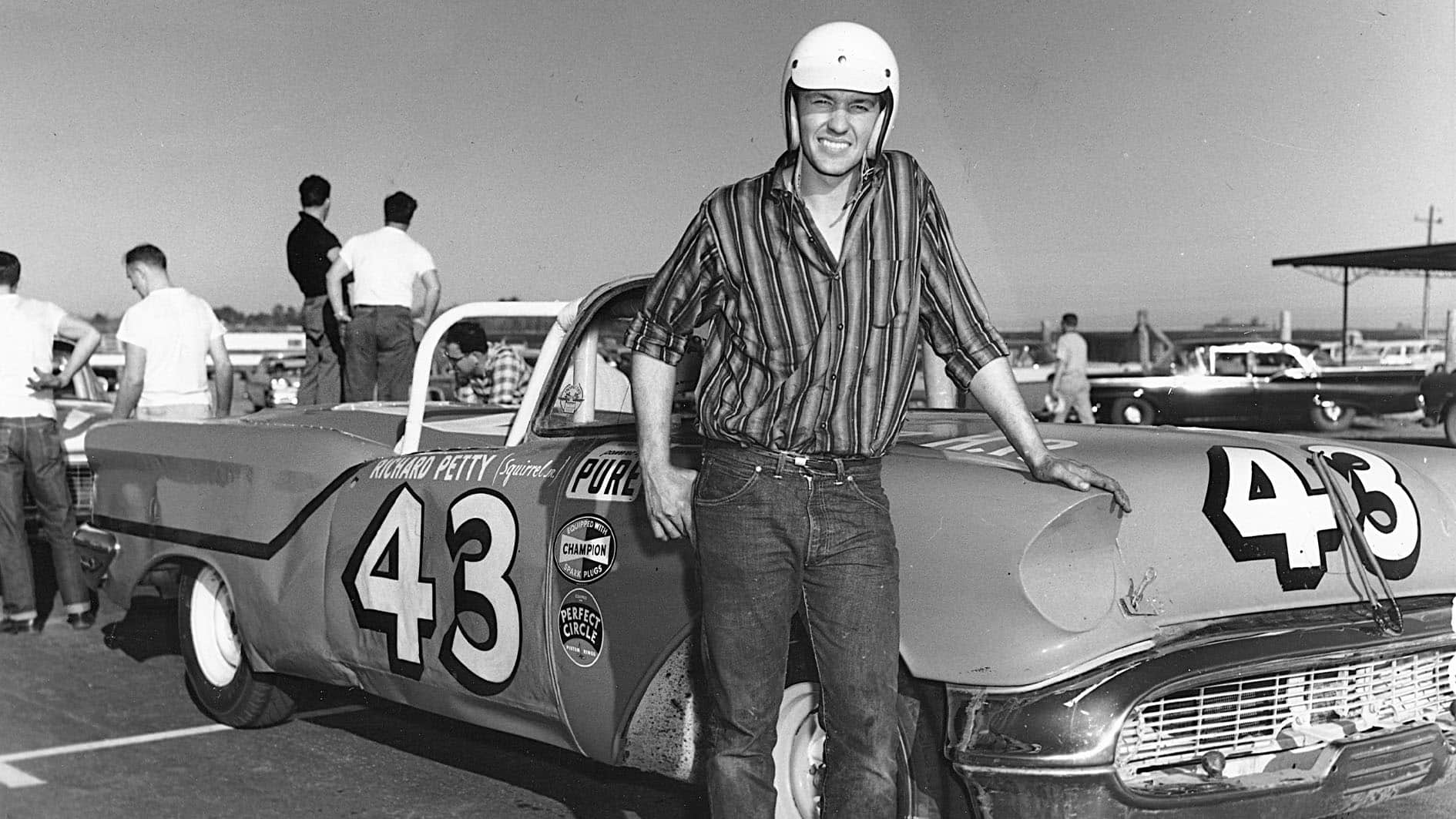

It was, of course, inevitable that Richard would race too. “I just fell into it,” he says. “I waited until I was 21 before I asked and Dad said, ‘There’s a car over there. Get it ready and you can drive it.’” It wasn’t so much a father’s indulgence, more that Lee reasoned if the boy was good he’d bring in more money than it cost to run him.

“When I started in ’58-59 I was still learning and Dad was still winning. In ’60 I got to win three races and then I raced him quite a bit.” In fact, he almost won four but after taking the flag first at Lakewood, he was overtaken on the slow-down lap by Lee, still charging flat-out for a further lap. After the race Petty Snr insisted the officials had hung out the flag a lap early and demanded they check. He was right, Richard’s win was removed and handed to Lee. Says Richard, “It was a lesson that you have to earn things, you don’t get them given.” What he’d earned, in fact, was a yearly prize money total of $35,180, well up on the previous year’s $7,630. Most went into the business, with Richard taking a salary of $100 per week and a percentage of the winnings. When he suggested he might have his salary raised. Lee told him that was fine…so long as he paid for every car he wrecked.

1960 was, in fact, a big year for Richard; his wife Lynda gave birth to their first child, Kyle.

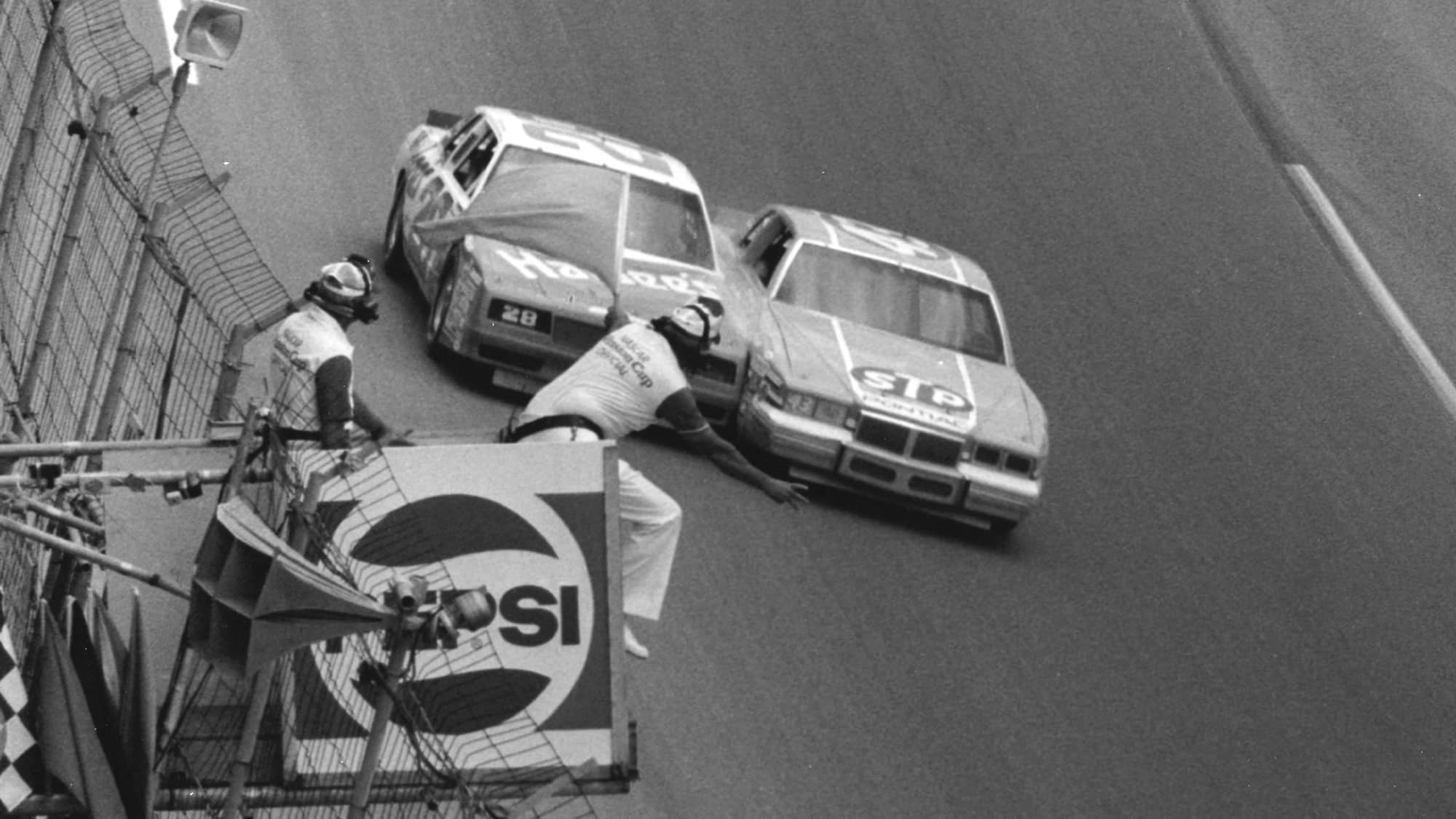

Lee’s career came to a dramatic end the following year at Daytona. Richard had just returned from a hospital check-up, unhurt, remarkably, from an accident in which he crashed through fencing and landed in a car park below. He arrived back just in time to see Lee get shunted through the fence from behind. He was badly hurt and though he briefly returned, he called it a day soon after.

Petty at first ever Daytona 500 in 1959

Getty Images

Not long after, Lee handed over the running of the entire team to Richard, with Maurice and cousin Dale Inman crewing for him. Lee took to playing golf, a pastime he pursues to this day. Interviews, however, are out. He evidently enjoys playing the role of curmudgeon. Richard: “Oh, he still comes in every once in a while, tells us how to set the car up, what we’re doing wrong, how they did it in his day.”

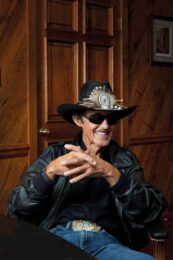

The Petty lineage was more than safe in Richard’s hands. As well as building up a prodigious winning record on the track, he was Mr Charisma off it, in complete contrast to his father, and was soon idol to an ever-increasing army of fans. STP car number 43 became the most widely recognised racing car of all and, out of it, Petty became an American stereotype; long lean figure draped in denim, snakeskin cowboy boots, stetson, wrap-round shades, cigar, all illuminated by a flashing white-teeth smile as wide as the Mississippi.

The King nickname was hard to argue with; he took 101 wins in the ’60s alone. Even a switch from his beloved Plymouth to GM in the late ’70s didn’t hurt his form. He didn’t retire until ’92, though the famed speed and aggression were long-gone. “I always felt that the Good Lord gave me 25 years of good luck and I was trying to stretch it to 35,” he says.”I knew I weren’t as good as what I was but I couldn’t figure why I couldn’t still win a race now and then. Finally I woke up one day and thought, ‘you know we’re going to need to get out of here while we’ve still got everything intact.”