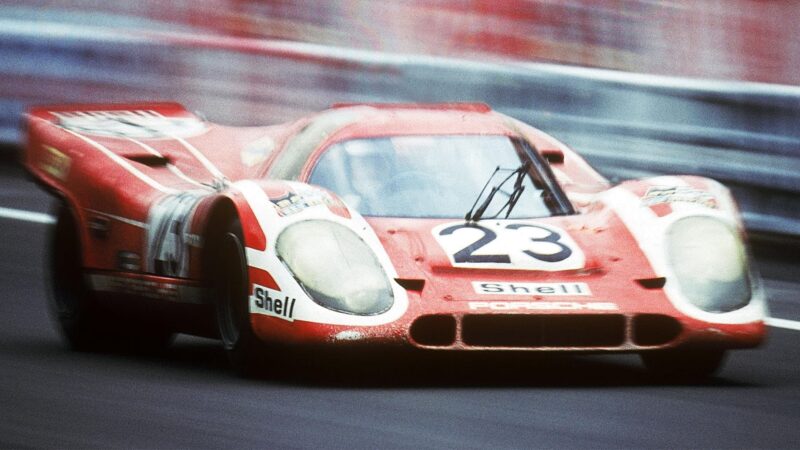

Attwood’s first meeting with the white monster came at Le Mans, just a few weeks later. “I wasn’t particularly keen, but someone said: ‘You, Herr Attwood, will be driving the 917 with Vic Elford’, and there wasn’t much more to be said. There was a hell of a row that year, because the car was fitted with these little movable wing flippers and there was a big protest. Eventually, Rico Steinemann talked to the organisers and threatened to withdraw every Porsche from the race which was about half the field, so we were given the go-ahead. The funny thing is that those flippers were totally ineffective anyway. I doubt if it would have made a scrap of difference if we’d taken them off.”

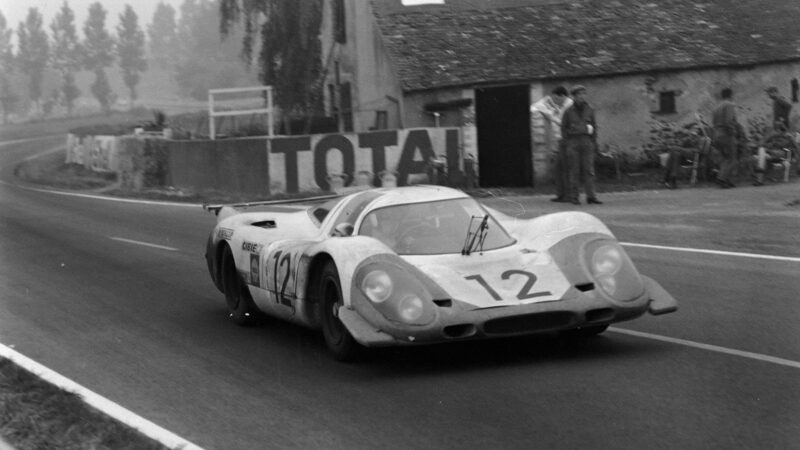

Practice confirmed all of Attwood’s worst fears. “The further you went clown the Mulsanne Straight, the less you could see through the rear-view mirror, because the back of the car was just coming off the ground. At the kink, you had to brake and downshift, things you wouldn’t dream of doing in a decent car. The other problem we had was these new Goodyear tyres on very narrow wheel rims, which started chunking at speed. That was fortunate from my point of view because it meant we had to slow down a bit on the straights… which is exactly what wanted to do.”

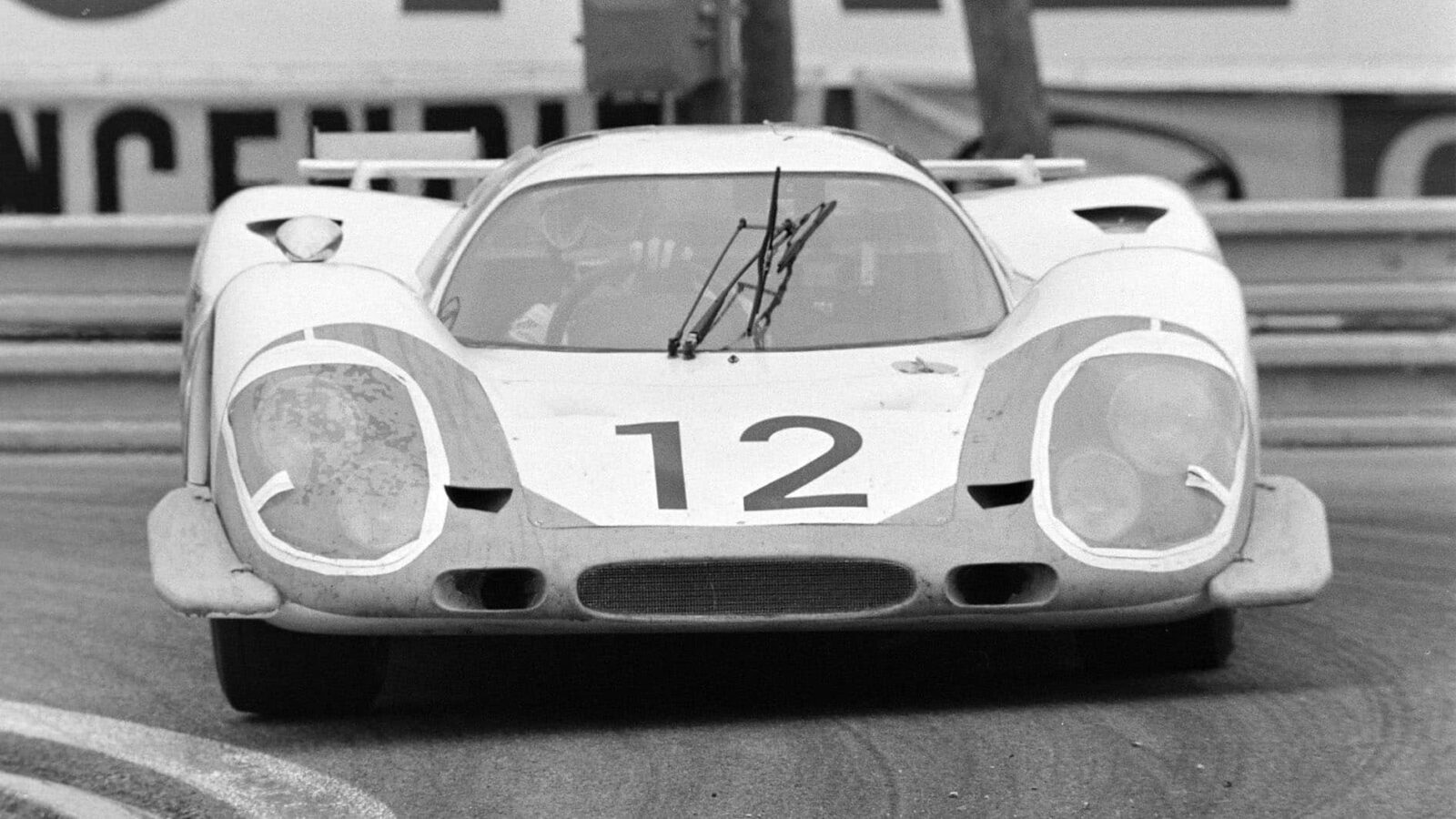

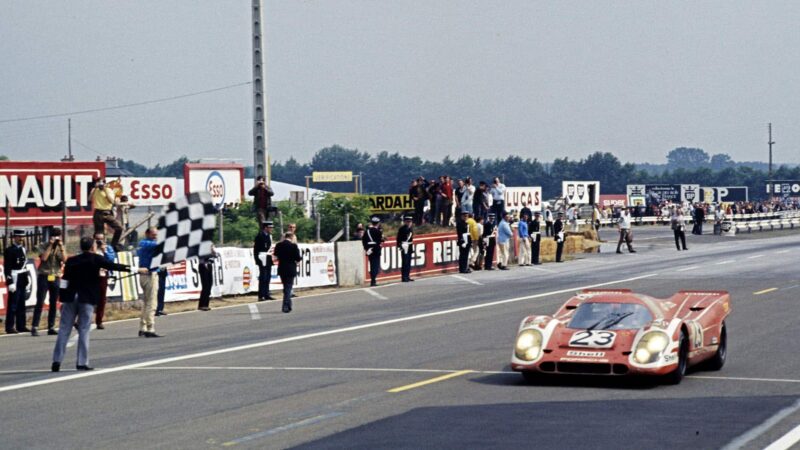

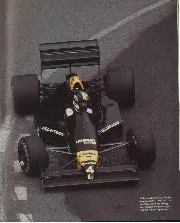

Much improved 917 dominated in 1970

Getty Images

Despite all the problems, though, the new Porsche was clearly in a class of its own. Two works cars were entered one for Rolf Stommelen and Kurt Ahrens, the other for Attwood and Elford, and they dominated practice. Stommelen qualified on pole with a lap that was 13 seconds quicker than the pole-winning time from the year before. It was quicker even than the 7-litre Ford Mk4s managed in ’67, even though the circuit had been lengthened and slowed down considerably with a new chicane before the pit straight.

“There’s no doubt about it, it was massively quick,” remembers Attwood. “They timed one car at 235mph on the Mulsanne Straight, which was 20-30mph faster than anything they had ever clone before. Looking back, we could probably have stroked it, like Gardner and Piper had done at the Nürburgring, and we would have won so easily.” But, as Attwood also recalls wryly, drivers like Stommelen, Ahrens and, particularly, Elford, were not likely to do much stroking. “They would just take the bull by the horns and go for it,” he says. “And you can’t afford to be a laggard so you have to go along with it as well.”