Walker’s 1951 Le Mans win was certainly a great achievement, but arguably less so than his exploits with the much-mocked V16 BRM, which Stirling Moss once described as ‘The worst car I ever drove’. Judged by any standards, the V16 was a difficult car to conduct at both low and high speeds, but the gentlemanly pilotes of the early 1950s did not complain, even when Reg Parnell and Peter Walker brought their recalcitrant mounts home in fifth and seventh positions on the occasion of the 1951 British Grand Prix at Silverstone, their legs so badly burnt by heat from the engines and exhaust systems that even walking was painful.

Gregor Grant reported: “Reg Parnell and Peter Walker saved the day for British motor racing. Their heroism in sticking to their task whilst suffering from agonising burns will enable the BRM designers to go ahead and modify the cars to make them completely raceworthy.” Still nursing his burns, but dismissing them as little more than “a bit of a nuisance”, Walker turned up at Dundrod to drive the C-Type in the TT. Jaguar cleaned up. Moss won at an average speed of 83.55mph, Walker came in a dutiful second at 82.57mph and the Johnson/Rolt car finished a creditable third at 81.31mph.

At the end of the season, Peter Walker returned to Herefordshire to attend to his farm, but son Tim remembers that there was always time for fun. “Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton were great friends and they used to come and stay with us,” he says. “They had famous parties, of course, and sometimes they seemed to go on for ever. On one occasion, after a particularly long night out, the police arrived to ask my mother if they could open the boot of father’s Bentley; they had ‘reason to believe’ that the signboard belonging to The Trumpet pub near Ledbury lay within. Mother assured them that they must have been mistaken, but they insisted on looking anyway. Sure enough, the pub sign was in the boot of the Bentley and the police made their displeasure felt in polite, but not uncertain terms. The sign was duly returned.

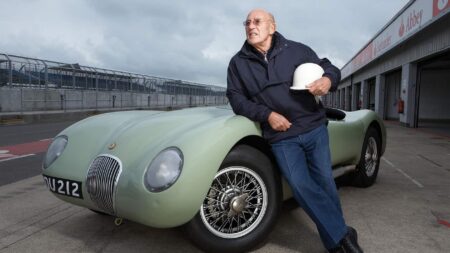

Walker driving the BRM V16 to a painful 7th place at the 1951 British GP

GP Library via Getty Images

“Stirling Moss and Peter Whitehead came to stay occasionally too, but although they enjoyed a laugh and a joke, neither were drinkers, unlike father, Tony and Duncan, and didn’t therefore get up to the same sort of pranks. I recall Peter Whitehead trying desperately to straighten a pig’s tail on one occasion, though.”

Duncan Hamilton’s widow Angela recently recalled another occasion when the Walkers and the Hamiltons met at a restaurant after a race meeting at Goodwood. “Not content with sitting down to eat and drink, Peter brought a large number of chickens with him and let them loose in the restaurant,” she laughs. “He was a great chap, always joking and clowning around, but deadly serious when he was driving. Peter was very skilful, fast and brave; he told me once that he could have gone a lot faster during the night practice for the 1951 Le Mans, but had forgotten to take his sunglasses off and couldn’t see very well. A super chap; we all loved him very much.”

“He was fast in the car and easy to get along with – a regular guy – which is why I always preferred him as a co-driver” Stirling Moss

Stirling Moss who, at that time was Jaguar’s number-one driver, rated Walker very highly indeed. “He was fast in the car and easy to get along with – a regular guy – which is why I always preferred him as a co-driver,” he says. For 1952, Jaguar appeared at Le Mans with the ill-fated long-nose, long-tail C-Types, The restyling exercise was not a good idea as it turned out, and engine overheating problems saw that years’s French classic fall to Daimler-Benz, whose new 300SL ‘Gullwings’ heralded the German company’s return to international motor sport for the first time since before the War.

There was, however, one high point during this season for Jaguar when Peter Walker took a C-Type (chassis number XKC 001) to Shelsley Walsh and smashed the sports car record with a formidable time of 41. 14sec. Later in the year he took the record at Prescott with a remarkable best of 47.53sec. For many, this was the first time they had seen a C-Type Jaguar, and at both hillclimb venues, Walker’s performance in the car with his inimitable spectacular style caused a sensation, and brightened up the lives of a good few motoring enthusiasts who were still recovering from the dreary aftermath of the War.

By 1953, Peter Walker was clearly enjoying his motor racing, but his private life was beginning to change. Patsy, a “sensible, charming girl,” according to Angela Hamilton, was quickly tiring of her husband’s lifestyle. Being a tall, dashing, good-looking chap, Walker was rarely short of female company either. After the breakdown of his marriage, he sold his farm, imbibed a little more from time to time and carried on racing.