“It’s a three-cornered track and as I came off of 3 I had a run at Rahal and was committed. As I pulled out round him he pulled out to go around Brayton, so I had to watch him and I saw a guy, Corrado Fabi, warming up down on the apron. I stayed as close to Rahal as I could because I was already committed, going through there like that as this car was coming out of the pits. As we went through I’m watching Rahal’s corner because I gotta stay right on him to make sure I miss Corrado. As you go by you watch him out of your peripheral vision, watch him go by, you know how fast you’re going by, how long it takes before you’re gonna clear him. So I was watching Fabi going by and watching Rahal and I thought okay, it’s clear, we’re gonna make it. But Fabi was warming up and just as I went by him he stood on the throttle and picked up speed. So instead of me going by, he started staying with us. I thought we were clear but we hit as I pulled on to my line, and I went under the guardrail. So it was a combination of me being over-anxious and putting myself in a bad position. In a race, obviously you don’t have guys warming up, but in practice you do.”

The Penske March dug its nose under the inside guardrail, tearing off the front bulkhead and smashing both of his feet. It would be five months before he drove again.

“I was in the hospital, basically, for three months, two months in Indianapolis, another month in California, then in a wheelchair another month or so after that. I’d still use the wheelchair or crutches to kinda hobble around at the end of five months, and we went to Phoenix to test and they basically had to pick me up and sit me in the car.

“At that time I had everything just padded up. My ankles were bad and I just couldn’t use them very hard. They were tender. Fortunately you don’t have to brake much on an oval, and I left foot brake everywhere. Matter of fact, I didn’t use the clutch before the accident either, so that was a plus. It was one less thing I had to worry about.

“Anyhow, we did the test and I ended up running quicker than Sullivan, so that was worth six months’ therapy, to get back in the car and run that good. First time out I went out and warmed the car up, came in and stopped, then I went out and started leaning on it a little. When I came in the guys leaned over and said, ‘How is it?’ and I said, ‘It’s pushing a little bit in Three and Four but it’s neutral in One and Two’, and they just cracked up and started rolling on the ground. I’d forgotten about my feet already and was thinking about the car, and they were wanting to know what my feet were like. It felt good to be back in it, to take my mind off everything else.

“I didn’t have a problem getting back in the car after the accident, because I knew what caused it. If I had done something that I didn’t know, something had happened where I’d made a mistake and didn’t realise it or what ever, yeah it would make me think about it. But if something happens and I know what caused it, okay. Every time I’ve ever spun a car, I’ve known exactly what caused it. Either I ran it in too deep, jerked it or got on it too soon. You know, I screwed up. It’d drive me nuts if I didn’t know what caused it. I couldn’t get back in the car. But by knowing, either what I did or what broke, it’s one hell of an incentive not to do the same again!”

The same sentiments were evident at Indy in 1991 when, after crashing in qualifying when a wheel worked loose (and breaking another bone in those damaged feet), he quietly stepped into the spare Penske and stood it on its ear to take the pole. It had been the first time in his 13 years at Indy that he’d ever spun, but within only six laps he had recorded 226mph. Afterwards, predictably, he was more concerned that the mechanics on the spare Penske got their due share of credit.

“It took a long time. A long time,” he said of his recuperation after Sanair. “I’ve still got pain, every day. I broke every bone in my right foot, half of them more than once, and half the bones in the left foot.”

In 1985 he missed all of the road events, not because he couldn’t shift gear because in any case he wasn’t using the clutch anyway, but because he just couldn’t push the brake pedal hard enough. When Johnny Herbert had a similar problem with Benetton in 1989 he was sacked; Penske valued its star rather more highly and spent a lot of time experimenting on his behalf with different brakes, master cylinders and power assistance to help him out. Gradually he built up his strength, and though he had to use a different size master cylinder to his team-mates, one with greater pedal travel which he confesses he didn’t like, he finally got back to the point where he could use a standard configuration. You sense he took great pride in that, although he’d never put it into words. Sadly, though, street circuits in particular would ever after take a toll on him.

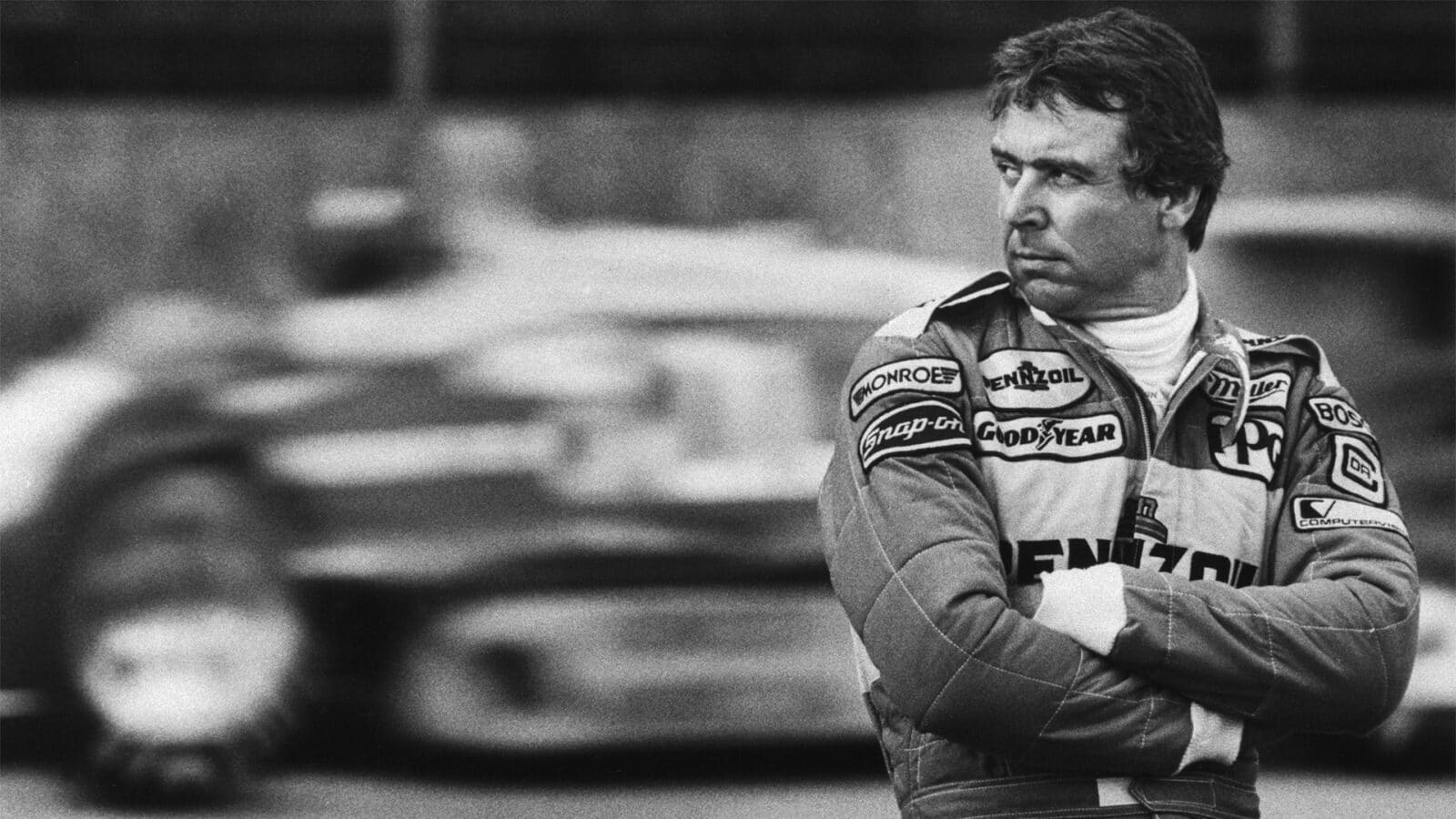

Rick Mears was forever a oval specialist — but his 1984 injury scuppered his road-running hopes

Getty Images

As he recovered he concentrated on developing the new Ilmor Chevrolet engine, and to prove that the fire still burned he took the pole at Indy and again, at a record 223.401 mph, at Pocono. He led more laps than anyone at the Brickyard, and finished only two seconds behind Rahal and Kevin Cogan. He stuck with Penske throughout the drought of ’86 and ’87, and his loyalty was rewarded with his third Indianapolis victory in 1988. Immediately after that he won again at Milwaukee, and he took the poles at Pocono and Michigan too. Well and truly, he was back. In 1989 he was second only to team-mate Emerson Fittipaldi in the national title, winning again at Phoenix and Milwaukee, and finishing tops at Laguna Seca.

It was the year that took him right back to the frontline, and the Californian success was his first road course victory for eight years. He backed it with another, the Marlboro Challenge, at Nazareth in 1990, which supplemented another Phoenix success despite a tangle with clumsy backmarker Randy Lewis. In 1991 it was one of my career highlights to watch him win at Indy. There, in the closing stages, Michael Andretti went round the outside of him to lead after a restart under the yellow. A lap later, at full racing speed, Mears pulled the same trick on Michael and sped away for his fourth triumph. Sitting in the bleachers between Turns 1 and 2, with his father Bill and mother Squib, and sons Clint and Cole right in front of us, keeping us informed by radio of his tactics and progress, I was conscious of watching history being made. But somehow I always thought he’d be the first man to win five Indys…

Now, of course, the F1 exodus to IndyCars has aroused great interest, but back in 1980 things were still happening the other way round, and Mears came close to a deal to run with Brabham as Nelson Piquet‘s team-mate. He tested a BT49 at Paul Ricard and Riverside, and he was fast. “I felt good about it, and I satisfied my own ego,” he told me at Milwaukee in 1990. “I knew I could make up time and I was taking it easy, I didn’t want to make any mistakes and look like an idiot. It took a little time to get used to it, it’s just like anything you jump into.

“We did the two tests at Ricard and then we went to Riverside which was a track I knew, although it wasn’t really the same because we had chicanes put up in about three different places so we could test the Weissmann gearbox. We ended up about three seconds a lap quicker than Nelson. I know where the time was made up. After the run Gordon Murray said, ‘I can see where you’re working out most of the time, around Turn 9’. It was my favourite corner on the whole race track. Nelson didn’t like that one. It’s slightly banked and right up against a wall. The chicanes really changed the track from what I knew, though, so when we ran quicker than him there, that really satisfied my ego that I could do it if I wanted to. That we could be competitive without a problem.”