The Motor Sport interview: Jochen Mass

The German multidisciplinarian on La Sarthe success in a Sauber, his reasons for exiting Formula 1 and why he can’t keep away from the Goodwood Revival

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

Jochen Mass, grand prix winner, Le Mans winner and still racing historic cars, is a man who can look back on a career that has seen him on the grid for almost every category of the sport. A versatile all-rounder, yes, but also a man who is as happy on the sea (he’s a former merchant seaman) as he is on the track, who thinks and speaks deeply about life, about the highs and lows of such an eclectic career. Despite his success in so many categories he is too often referred to as the ‘other driver’ involved in Gilles Villeneuve’s fatal accident at the Belgian Grand Prix in 1982. More about that later.

Having climbed the ladder all the way to Formula 1, Mass raced for Surtees, McLaren, ATS, Arrows and March between 1973 and 1982, winning the Spanish GP in 1975. After Formula 1 he raced sports cars through the ’80s and early ’90s, winning Le Mans for Sauber-Mercedes in 1989 and standing on the top step at Sebring, Mugello and Salzburg for Porsche. His success in endurance racing with Porsche and Mercedes re-established his credentials and allowed his talent to shine.

Today, age 78 and living in southern France, he retains his connections with Mercedes and races in historic events.

German Formula 3, 1971, with Jochen Mass on one of his favourite tracks – the Nürburgring

McKlein

Motor Sport: Let’s start with the bizarre social media news that you had died. How did you deal with that, bearing in mind you are one of the sport’s great survivors?

JM: First I called my wife because a friend had told her about this stupid ‘news’ that had appeared on social media. I mean, how do you deal with these idiots? Most people just ignored such a crazy piece of fake news, which seems to occur on social media these days. Anyway, as you know, I am very much alive and well – and still racing historic cars.

You grew up in Germany immediately after the war and your father died when you were just eight years old. This was surely a tough start to life in war-ravaged Munich?

JM: It was tough, yes. On the one hand I felt the sadness and shock of losing my father but, and this may seem cynical, I felt liberated, free from the pressures of him pushing me in directions I didn’t want to go. So in that sense there was relief. He enjoyed his cars, always had a nice car, and he’d got me a pedal car which I drove around the rubble in the streets, but he had no interest in racing. That all came later for me.

On the ’Ring again, this time heading for the podium in the 1974 ETCC racing a Ford Escort RS 1600

LAT

After school you joined the merchant navy and went away to sea for years. What did you learn from that experience?

JM: It made me grow up pretty quickly in a small community floating on the ocean. I loved being at sea, being on watch at night, just the flying fish and the whales for company during those long dark shifts. That’s why, when I became a professional driver, I had my own sailing yacht, a wonderful old top-sail schooner, where I would relax between races. We sailed it across the Atlantic, went down to South America, all over. They were good days. You have to be very disciplined on a boat at sea. You learn to make the best of things, deal with the challenges of storms, look after that space that is your home from home, away from the pressures of racing.

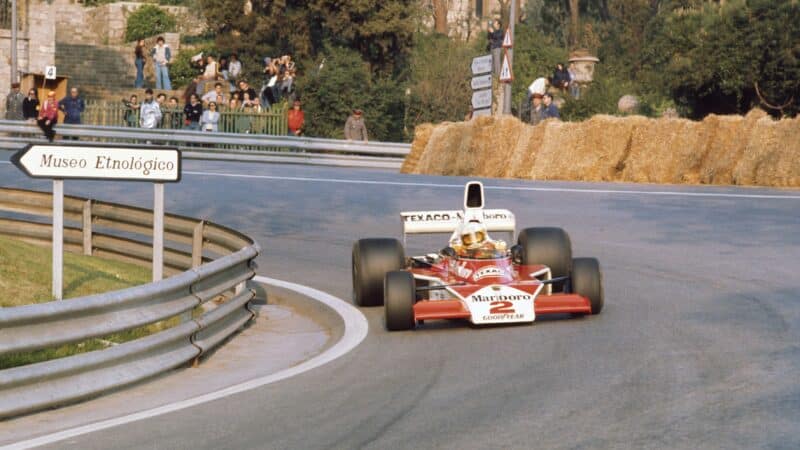

Mass has fond memories of the McLaren M23 in the mid-1970s, but did other drivers have superior Cosworth engines?

Your career began in hillclimbs – a notoriously dangerous activity in those days.

JM: Yes it was dangerous but I did it because I loved it – we all did. You knew you could have a big accident but you had no fear, you tried not to be reckless, and I just loved the racing. I did well, I was fast, and Ford came to me with a contract in 1970, and suddenly I was a professional race driver.

“Watching as a youngster gave me the burning desire to race at the ’Ring”

With Ford Cologne we had good cars. They put me on hillclimbs at first and then we won the German touring car series. Ford had taken a group of drivers to Zandvoort for a test; I’d never driven the Escort before, never seen Zandvoort. Helmut Marko was there. He was quick – he would have been another Austrian world champion had he not lost an eye at Clermont-Ferrand.

I was within tenths of his times, was given a contract, and they asked me how much money I wanted to race the Cologne Capri. You can’t answer that question. How much is enough? Will I ask for too much or too little? They came up with a figure, 70,000 marks, a company car and expenses. I nearly fell of my chair – until then I had earned peanuts as a mechanic and I’d been racing borrowed cars. It was unbelievable. Now I could have three meals a day and live like a professional race driver.

A smile at Interlagos in 1976 (the McLaren man would finish sixth), but the dangers of F1 started to weigh heavily for Mass

You forged a reputation for being exceptionally fast around the Nürburgring. What was it about that circuit that gave you so much success?

JM: It was simply a magic circuit. I’d spent a day learning it in a friend’s car, and I had a special feeling for the place. For me it had this tremendous atmosphere, both as a driver and a spectator. Watching the cars there as a youngster, seeing the drivers at work through all those corners, gave me the burning desire to race at the ’Ring and conquer its challenges. You could make a difference there, over such a long lap, through the forest, up and down the hills, all those twists and turns to memorise. We beat the BMWs there with the Ford touring cars, and I won an F2 race there. Maybe my best performance was in ’76 in the McLaren M23, which was a very good car. I started the grand prix on slicks, when everyone else was on wets, and I had a 50sec lead when Niki Lauda crashed. When the race restarted after Niki’s accident I came in third.

The frustrating problem was that the other Cosworth runners like Andretti, Hunt and Scheckter, they had much stronger engines and I only discovered that in the ’90s when Keith Duckworth told me what was going on. I was really angry when he told me that I’d never had a chance against them with my engines. James [Hunt] always had the best engine. He was a big star in Britain, and yes, things could have been different if I’d had better engines but maybe I was too docile, too complacent, at the time.

Mass, right, sharing the steps with, from left, Jody Scheckter and James Hunt, German GP ’76

Your first, and only, F1 victory came in Spain in ’75 under tragic circumstances when Rolf Stommelen crashed on a terrible weekend for the sport at Montjuich.

JM: We all wanted to go on strike at the time. The guardrails were not fixed in place properly, no nuts on the bolts, and the FIA had not inspected the track in time for the race, and of course they should have done something about it. We all agreed we would take it slowly, pretend to race. Fittipaldi withdrew and went home, but it was all agreed. When the flag dropped that was all forgotten. Andretti tangled with Brambilla and ran into the back of Lauda, who then hit the other Ferrari of Regazzoni.

“I was dazed but otherwise I had no other injuries. A miracle”

On lap 25 the rear wing broke on Stommelen’s Embassy Hill. The car flew over the barrier. Four people were killed and Stommelen was injured. The race went on for another four laps. I overtook Ickx and had the lead when the race was stopped. It was crazy. The FIA should never have allowed that race to be run without proper guardrails in place, and I took no pleasure in my first F1 victory, believing I would win more in the future. It wasn’t really a race win, with half points, but I know there’s a stone plaque in Montjuich Park with my name on it because my children sent me a photo of it years later.

Mass’s sole F1 victory came in the 1975 Spanish GP, but the day ended in tragedy

You’ve always lived with people talking about your involvement in Gilles Villeneuve’s fatal accident in qualifying at the Belgian GP in 1982. How did you deal with that and how did it effect your career at the time?

JM: It didn’t really change my life because nobody ever blamed me for what happened to Gilles. Niki [Lauda] had said something about what I should have done after the race but he came to see me at the next race and told me that he never meant to suggest I was to blame. Many years later Jacques told me that he and his family had never said, or considered, that any blame should be put on me, and I had always felt the same.

I was on my way back to the pits, saw him coming up fast behind me and moved to the right. The quick line there was on the left, but his left front wheel touched my right rear. Next day, in the race, my engine blew up at the very same place where the accident had happened and I stood there at the side of the track and saw it all again in my mind, which was a sad and sombre moment.

Mass, left, with Manuel Reuter and Stanley Dickens – Le Mans 1989.

You had two very big accidents, in the ATS and in the March – accidents that were potentially fatal, but you survived.

JM: Yes, the commentators at the time said I could not have survived those accidents, that I must be dead, and that’s why I am sometimes known as the ‘great survivor’ from such a dangerous era. The worst, the one that persuaded me to retire, was the collision with Mauro Baldi going through Signes corner at Paul Ricard in ’82. My wife was watching on TV with Pam Scheckter and the commentator said I must either be badly hurt or dead. I went through the catch fencing, into the tyre wall, then the car catapulted into a spectator area and caught fire.

Once the marshals had extinguished the flames I felt better, realised I was not going to die. My helmet was broken, I had pain in my shoulder, I was dazed, but otherwise I had no other injuries. A miracle. It all happened in slow motion. Somebody must have been looking after me, and I knew it was time to get out of Formula 1, and the team was simply not performing. It was a great shame but I knew it was right to stop and there were still the sports cars so I could continue racing. I believed it would be safer too, but of course it was still very dangerous in those days, very high speeds and the cars were still not as safe as today.

Leading Le Mans 1991

Sports cars and endurance racing went well for you. A win at Le Mans and a string of other long distance podiums.

JM: Porsche had very good cars at that time, the 956, the 962, they were magic cars. I first drove the 956 at Le Castellet, to familiarise myself with the instruments, the steering, the way the car behaved. After a couple of laps I didn’t recognise the circuit any more, the car was so fast, the corners were just a blur; I thought, “Where am I?” You had to talk yourself into taking some of those corners flat, you had to believe just how good the car was. Those Porsches were the best at the time, in a different league. There were some accidents. The younger drivers thought they were invincible, like Bellof, who was so talented, but he could be a little reckless.

“The slower cars were on your racing line. I didn’t like that about Le Mans”

I hated Le Mans to begin with, the speed differentials were a problem, you were doing over 200mph on a French country road. You had to be looking ahead and looking behind. The slower cars were sometimes on your racing line. I didn’t like that about the race. It was worse at night, there were too many accidents. I felt it was not justifiable any more, but Le Mans is a magic name worldwide and had become disproportionately important in the calendar. Of course winning for Sauber-Mercedes in ’89 was a proud moment and, looking back, I am pleased to have that victory in my career. It’s a tough one to win, you need some luck, and everything has to be perfect. In ’91, with the Sauber-Mercedes C11, we had been leading easily for 17 hours and then the engine began to overheat. Alain Ferté brought the car in with two hours to go and they found a broken alternator bracket, allowing the water pump belt to come off, and so the engine was cooked and our race was over. I was so angry because Mercedes had spent millions to win this race and it ended thanks to a part that cost maybe €10. We would have won so easily.

The German is a Goodwood regular – seen at the Festival of Speed in 2017 to drive a Silver Arrows W125

Getty Images

You are still racing historic cars and have a special relationship with Mercedes. Is this just for the pleasure of driving some great cars?

JM: Yes, and I love events like the Goodwood Revival which is a weekend I never want to miss. The racing is wonderful but some people are trying too hard and it has become a little serious. We don’t want owners to build replicas and leave their priceless cars in the garage for fear of damaging them. The point is we want to see these beautiful cars out there and the Revival is the best historic meeting of the year. Over the years I’ve been lucky to drive some off the greatest racing machinery in the history of the sport.

Plenty of Union Jacks at Le Mans in 1989 but the day belonged to the No63 Sauber C9

What’s your take on F1 racing today? It’s so much safer now but is it a better show?

JM: The cars are too fast, too aerodynamically efficient. Do the spectators want that, are they impressed by the speed and the minimal braking distances? I’m not so sure. There is too much emphasis on the cars and the technology. In the rain, the speed and the downforce throw up a rooster tail of water like a motor boat, making it impossible to see. I think it needs to be more of a drivers’ championship, with less importance on tech.

Despite the speeds maybe the cars are too easy to drive which is why we see so many youngsters come in and be immediately on the pace. Formula 1 is a big financial ‘machine’, the teams are too big, huge sums of money are involved, with engineers bringing new parts to almost every race. Anyway we can’t go backwards, and, of course, it is so much safer than ever before.

Mass remains captivated by motor racing history – here driving a 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300 SL at the Goodwood Revival, 2014