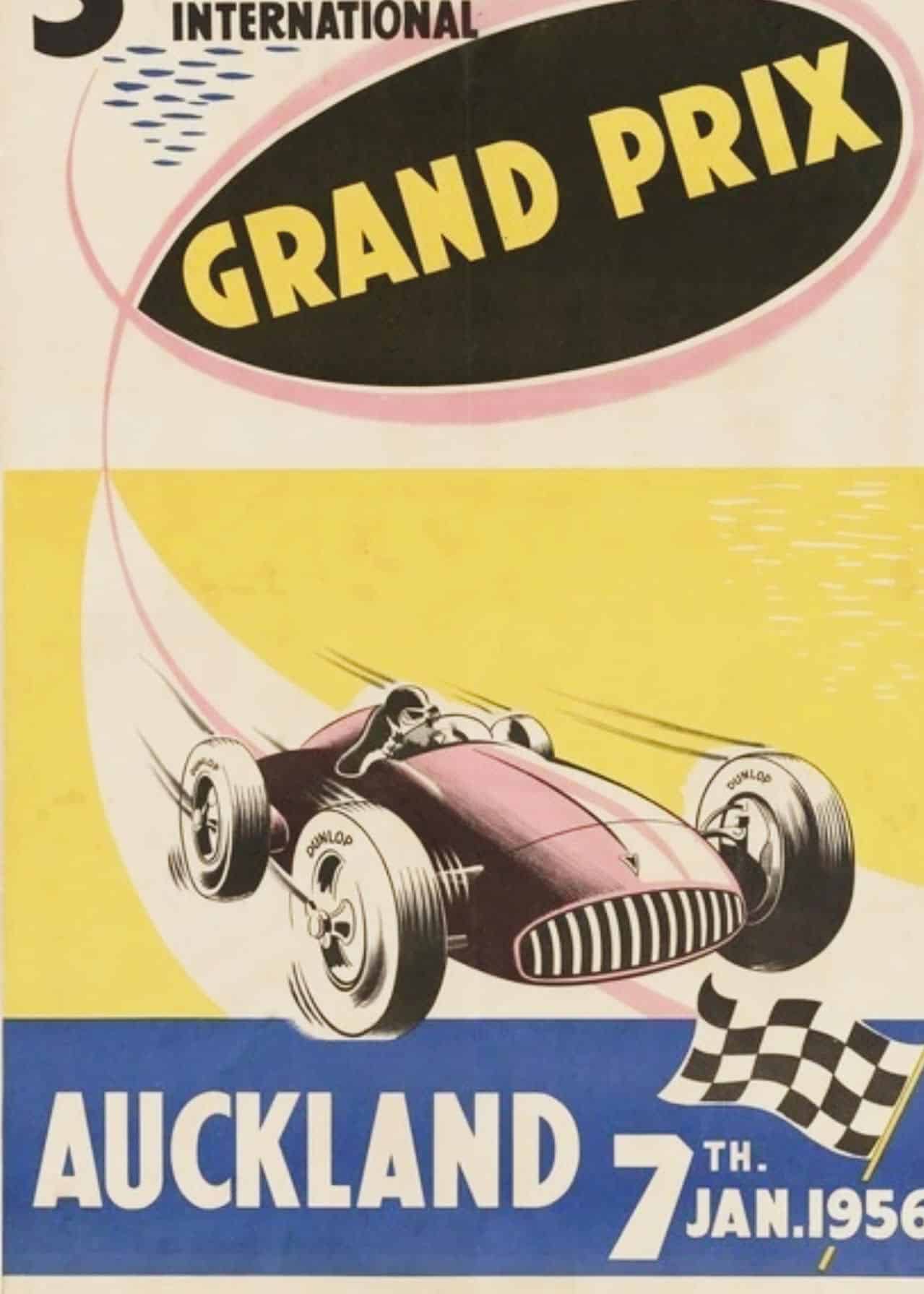

Aston Martin’s DP155: grand prix pioneer

With the brand back in Formula 1, Mark Bisset recalls where it all started with the experimental DP155 and how, after the trials of just one tour of New Zealand in 1956, it finally found redemption

Reg Parnell at speed in DP155 during its sole tour of New Zealand. Had it fared better, it could have kick-started a different grand prix trend for Aston

Grand Prix Photo

Aston Martin’s ownership structure and commercial fortunes have had more twists than a Federico Fellini movie in the 110 years since Lionel Martin and Robert Bamford commenced business. Perhaps the only similarities between Aston Martin’s first and latest grand prix cars – the 55bhp 1.5-litre 1922 TT and 750bhp 1.6-litre turbo 2023 AMR23 – is the stupendous wealth of their backers, first Count Louis Zborowski and currently Lawrence Stroll.

In exalted company at Dunedin in 1956; DP155 at the back behind the Whitehead and Gaze Ferraris.

T Selfe

As the David Brown Ltd-owned business focused on racing the DB2 and DB3 in the early-1950s, “the team suffered from a frenetic neurosis that they should really be competing in single-seater racing,” wrote AM historian Anthony Pritchard.

The Feltham technicians therefore created an F2 car by marrying a modified DB3 chassis with a 2-litre variant of the 2.6-litre LB6 engine. Assembled over the 1951-52 winter, it was rejected by technical director Professor Dr Robert Eberan von Eberhorst, and dismantled and forgotten. John Heath showed interest in the engine for his F2 HWMs but David Brown knocked that notion on the head, too.

Parnell at the controversial Ryal Bush road race.

Ryal Bush

In the autumn of 1953 Aston Martin contemplated F1 again, and this time proceeded with a low-priority project, busy as it was with DB3S sports car racing programmes, which made sense for the business from both product development and marketing perspectives.

Project designation DP155 was allocated with chassis number DP155/1 applied to an un-numbered DB3S twin-tube frame “in narrower single seat form,” powered by an alloy-head, 2493cc (83x76mm) triple Weber DCO-fed version of the Willie Watson-designed 2.9-litre Aston Martin engine.

“The team suffered from a neurosis that it should really be competing in single-seaters”

The gearbox was a David Brown four-speed unit, brakes were two-leading-shoe Girling with Al-fin drums, steering was rack and pinion and the suspension independent by trailing links, torsion bars, piston dampers with anti-roll bar at the front, and De Dion at the rear with trailing links and torsion bars, Panhard rod and, again, piston dampers. Works mechanics John King and Richard Green were among the constructors involved, while legendary stylist Frank Feeley designed the aluminium bodywork of a car in which the driver sat high atop the prop-shaft.

DP155 at Dunedin Wharf

T Selfe

John Wyer estimated an output of 180bhp on alcohol fuel, well short of the contemporary F1 Tipo 625 Ferrari and Maserati 250F, which were developing at least 200bhp by early 1954.

The twin-plug 1955/56 DB3S engine made 215bhp, but by then the F1 opposition were at 240/250bhp. Pritchard wrote “it seemed a futile exercise for Aston Martin, whose sports-racing cars were notoriously and persistently underpowered, to contemplate building an F1 car powered by a derivative of these engines”.

After its sole tour as a ‘works’ Aston racer, Geoff Richardson acquired DP155; he is seen here testing it at Snetterton in 1957

Autosport

After testing, the car was set aside in the workshop as sports car programmes were prioritised. DP155’s 2.5-litre engine was installed in DB3S chassis no5, which Reg Parnell drove to third place in the ’55 British Empire Trophy race at Oulton Park behind Archie Scott Brown’s Lister Bristol and Ken McAlpine’s Connaught ALSR.

“Aston Martin denied it was eyeing F1, but chatter increased when DP155 went to New Zealand”

This prompted rumours that Aston Martin was considering grand prix competition. It denied that, but the chatter gained traction when Aston confirmed Parnell’s plan to race DP155 in the Kiwi Formule Libre internationals in early 1956.

Parnell – a post-war star and works Aston Martin driver since 1951 – identified these events as offering useful race testing and earnings during the northern winter, perhaps in conversation with Peter Whitehead and Tony Gaze, veterans of the trip to the ‘Land of The Long White Cloud’.

DP155 at Wigram airforce base, one of New Zealand’s early post-war racing arenas.

T Adams

DP155 was fitted with the supercharged 3-litre engine Parnell and Roy Salvadori had used at Le Mans in 1954. It would have been competitive so equipped, but the engine exploded while Reg tested it at Chalgrove airfield in Oxford. The car was therefore shipped south with a normally aspirated 2493cc engine fitted with special camshafts, connecting rods and pistons.

The ‘British invaders’ comprised Stirling Moss in the family Maserati 250F, the two amigos, Whitehead and Gaze with their well sorted and fast Ferrari 750S 3-litre-engined Ferrari 500s, Leslie Marr’s streamlined B-Type Connaught-Jaguar, and Parnell.

Pre-war NZ racing was mainly confined to beach tracks, but post-conflict the sport grew substantially. The Otago and Southland Car clubs secured the Wigram RNZAF base for racing in 1948, and the Manawatu Car Club the Ohakea Air Force base. They staged the first NZ GP, won by John McMillan’s Jackson Ford V8 Special in 1950. Public roads at Mairehau, Christchurch were closed for racing for the first time in 1951 and a round-the-houses track near Dunedin’s wharves operated from 1953. When the first international NZ GP was held at Ardmore in 1954 the Kiwis had five meetings annually, three on airfields and two on road circuits.

Start of the NZ Grand Prix in 1956 at Ardmore. Moss’ Maserati lines up on pole and would win comfortably

Karjini

That 1954 grid was headlined by Ken Wharton’s howling V16 BRM P15 Mk2, Whitehead’s Ferrari 125 and Gaze in a supercharged factory HWM-Alta. Australians Jack Brabham (Cooper T23-Bristol), Stan Jones (Maybach), and Lex Davison (HWM Jaguar) crossed the ditch (the Tasman Sea), Jones victorious after Wharton’s BRM failed. In 1955 Prince Bira’s Maserati 250F won.

The first of the 1956 races was the NZ GP held at Ardmore Airfield, 25km south-east of Auckland, in the North Island.

Moss and his Maserati were a huge draw and he was favourite for the race, but his car, the two Ferraris and Marr’s Connaught were mistakenly shipped to Wellington instead of Auckland, so things didn’t get off to a great start.

Despite a mix-up in the shipping of his car, Moss was the star of the GP.

Getty Images

Moss, Whitehead and Parnell all took two seconds off Wharton’s two-year-old BRM lap record in practice, then Moss bagged pole from Whitehead, Gaze and Brabham in the Cooper T40 Bristol – first raced by Jack at F1 championship level at Aintree six months before – then came Ron Roycroft’s Bugatti T35-Jaguar and Parnell.

Parnell had a fraught start to the weekend when DP155 threw a conrod during practice, but Whitehead saved the day by offering him the Cooper T38-Jaguar that he his half-brother Graham Whitehead had campaigned throughout 1955. On its farewell tour and conveniently up for sale, a good showing would enhance its attractiveness.

Gaze led early, then Moss romped past and away for the balance of the 200-mile journey, lapping the field by the end of his 33rd tour. Some late-race excitement was provided when a broken fuel pipe sprayed fuel into his cockpit, but even after a splash and dash he won by nearly a minute from the Gaze and Whitehead Ferraris. Then came Marr’s Connaught and Parnell’s Cooper-Jag. Poor Brabham didn’t start, his gearbox case split as he warmed the car up in the paddock.

Leslie Marr’s Connaught leads Tony Gaze’s Ferrari 500 at Ardmore in 1956. Parnell would have to borrow a Cooper after the Aston broke a conrod

Getty Images

The circus then gathered at Wigram, Christchurch in the north-east of the South Island on January 21.

The Feltham crew ensured that a new 2922cc engine was flown out for DP155. Moss returned to Europe after Ardmore, his 250F was sold and put to good use by local aces Ross Jensen and John Mansel for the ensuing half-decade. New Zealand proved a happy hunting ground for Moss – he won the GP again in 1959 and 1962 aboard Rob Walker Cooper T45/Lotus 21-Climax respectively.

DP155 finished a distant fourth in the 71-lap Lady Wigram Trophy, while up front Whitehead was five minutes ahead of the Aston hybrid, winning from pole ahead of Gaze and Marr.

Gaze’s Ferrari ahead of DP155 at Dunedin

CANews

From there the racers travelled south to Otago Harbour city, Dunedin for the NZ Championship Road Race on January 28, which was run across 120km or 44 laps of a 2.74km course adjoining the wharves. The surface was rough and tough including a gravel section, just to add to the challenge.

Syd Jensen’s nimble, fast Cooper started from pole with Gaze and Arnold Stafford in a similar Cooper on the outside of the front row. Marr, Parnell and Whitehead were back on row three, while local lads Ron Roycroft, (Bugatti T35-Jaguar), Ron Frost (Cooper Mk9-Norton) and Tom Clark (Maserati 8CM) were on the second row.

While Jensen set the crowd roaring – the little Cooper hassling the bigger cars throughout, eventually finishing third and claiming the fastest lap – Gaze won from Parnell, Jensen, Whitehead and Clark. Marr started the race, did one lap to get his starting money and then voluntarily retired… he wasn’t impressed with the place or the circuit at all.

Unimpressed by the Dunedin track, Marr did just one lap in his Connaught-Jag, for the start money

CANews

The visitors then raced at Ryal Bush on February 4. The first Southland Road Race was 240km (41 laps) around a 5.87km circuit that Kiwi journalist Allan Dick described as “The Reims of New Zealand: three long straights with three tight corners and high speeds. But unlike Reims, Ryal Bush was narrow and lined with lamp-posts, hedges, ditches, drains and fences. Average speeds were around 150kph, making it the fastest circuit in New Zealand.”

Whitehead bagged pole from Marr, Gaze, Clark and John Horton in the ex-works/Gaze HWM Alta s/c, while Reg was back on row three in the Aston. Given the European experience of Whitehead, Gaze and Parnell they would have felt right at home in such a dangerous place. Whitehead won the race in a time of 1hr 35min from Gaze, with Parnell in a good but rather distant third place, with Roycroft fourth and Frank Shuter’s Cadillac V8 Special fifth.

With the tour over, the cars were shipped back to Europe or Australia while their intrepid pilots indulged in some deep-sea fishing round The Bay of Islands before Whitehead departed for South Africa and Parnell headed to the US for Aston Martin’s Sebring 12 Hours commitments (DNF in a DB3S shared with Tony Brooks).

Peter Whitehead’s Ferrari resplendent in colour ahead of its win at Wigram, 1956.

T Adams

By then the pattern of uncompetitive racing cars being sold to eager colonials was well established, so quite why DP155 wasn’t flogged on in the Antipodes in the manner of the Whitehead/Gaze cars is a mystery, but either way its role in this particular campaign was complete.

The car had spawned another idea and before long Aston Martin began work on the DBR4/250: a full-blown 2.5-litre RB6 powered, spaceframe, disc-braked F1 car which was tested by Salvadori and Parnell – by now Aston Martin’s team manager – at MIRA in December 1957, but that’s as far as the project went.

“Had DBR4s raced in 1958, the later F1 failures may not have happened”

Had DBR4s raced in 1958 the failures of competing with antiquated front-engined racers against the mid-engined hordes in 1959-60 might have been avoided, but who can criticise David Brown’s prioritisation of scarce resources into sports car programmes which yielded both a Le Mans win and World Sportscar Championship success for the superb DBR1/300.

Marr’s streamlined Connaught would wind up third in this

T Adams

So, unloved and lonely, the sole DP155/1 remained tucked away in a Feltham corner until John Wyer sold it to specials builder Geoff Richardson of Richardson Racing Automobiles, who fitted it with a 2.5-litre single-plug engine. Richardson told Pritchard, “I paid about £900. It was a great source of annoyance because John Wyer guaranteed it gave 190bhp, but on my test bed I only got 145bhp. Wyer had a twin-plug engine that he wouldn’t sell to me so I never spoke to him again. I made a 2483cc Jaguar XK engine fit and got nearly 200bhp on regular pump fuel.”

DP155 as it looks now as a DB3S Special, the slipper-like grand prix shape replaced by a sports car body modified to ape the works cars

Corey Escobar ©2023 Courtesy of RM Sotheby’s

Richardson raced the Aston-Jag twice before buying Brian Naylor’s ex-works Connaught B-Type. David Gossage bought DP155 late in 1957 on the condition that Richardson rebuild it as a sports car.

Fitted with the body of the Lord O’Neill DB3S/105, it was modified at the front with a simple oval radiator intake and then registered as ‘UUY 504’. Richardson sold DP155’s aluminium grand prix ‘slipper’ body to a buyer in Ireland, and it’s now fitted to a well-known Aston Martin Special.

Perfection down to the last bolt.

Corey Escobar ©2023 Courtesy of RM Sotheby’s

Gossage later sold DP155 to hotelier Greville Edwards, who had a bad accident in it that killed his girlfriend. Richardson then reacquired it, building a replacement chassis using “main tubes supplied by Aston Martin”. Further modifications included replacement of the torsion bar rear suspension with coil/spring damper units, fitment of a De Dion axle with a Watts linkage in place of the sliding guide, and a Salisbury ‘slippy diff’. The nose was reprofiled to a more aerodynamic form. Finally he finessed a 3-litre crank into a 2.4-litre Jag XK block to give a capacity of about 3.2 litres. Back together in 1962, Geoff raced and sprinted it and used it as a fast roadie before selling to Richard Bell in 1973.

Bell restored the machine to original DB3S shape and built a twin-plug engine, and along the way the no131 DB135 chassis number was applied. The car soon became a global investment commodity and passed through several owners in the late 1980s, during which time the body was modified to 1955 team specifications. The last owner was in the US, though the car was auctioned in August. While the lineage and provenance of DP155/1 is clear, the car now is quite different to the single-seater that Reg Parnell raced in New Zealand during that summer of 1956.

The 3-litre twin-plug Aston engine

Corey Escobar ©2023 Courtesy of RM Sotheby’s

Aston Martin has a longer history than most car-makers and DP155 stands as a mere blip in the company’s scale of achievements. But despite its early componentry being repurposed as a sports car, ensuring its oblivion as an F1 hopeful, David Brown’s toe-in-the-water 2.5-litre experimental grand prix machine should not be forgotten.