‘How I almost got the first Las Vegas GP cancelled’

Really? No doubt about it. Back in 1981, it was only the intervention of the FIA president that saved the Las Vegas Grand Prix... and an impertinent Limey hack from a trip to the cooler, as Mike Doodson recalls

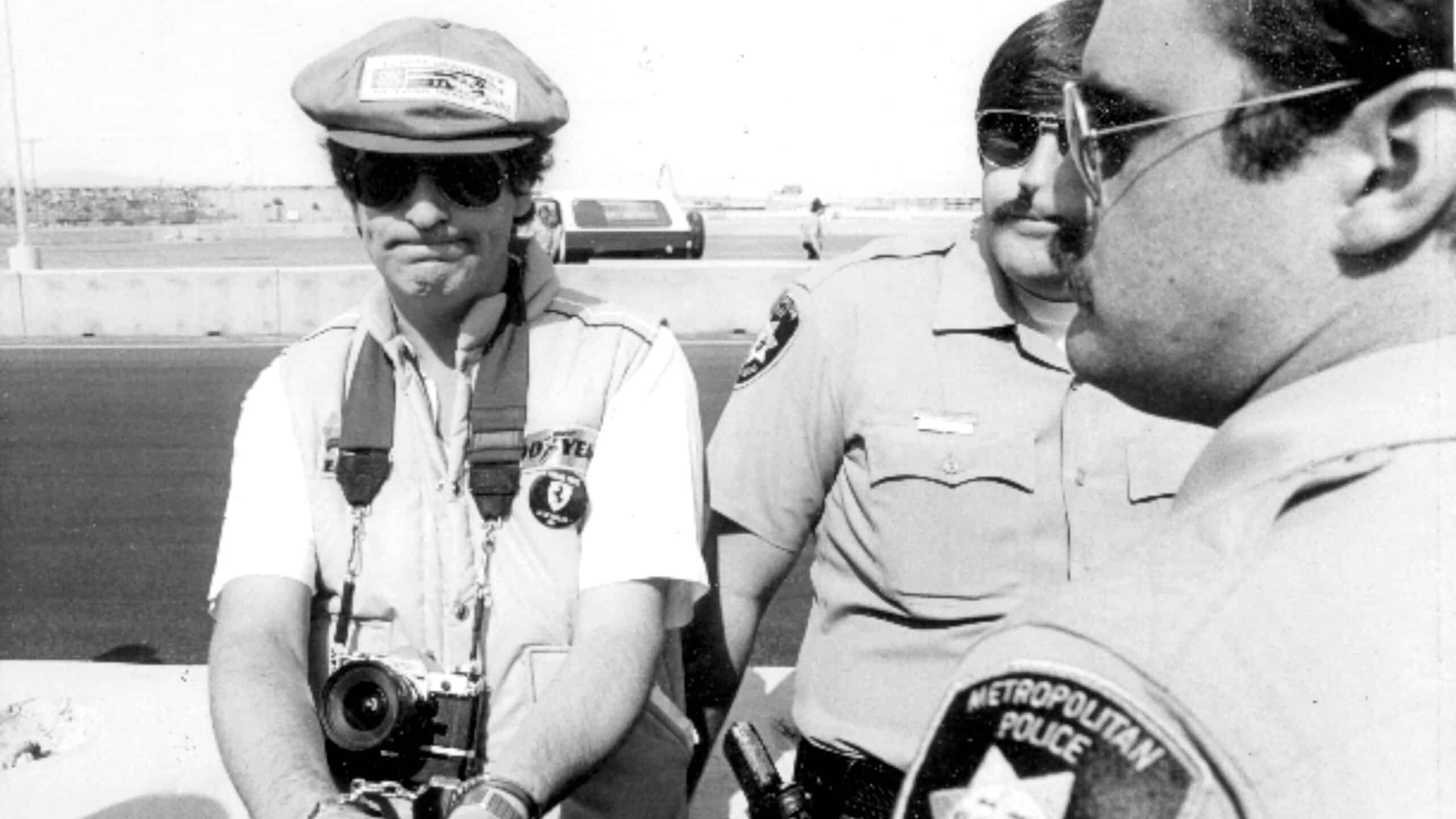

Our hardened criminal faces the music... but he deserved to be cuffed for that hat

Grand Prix Photo

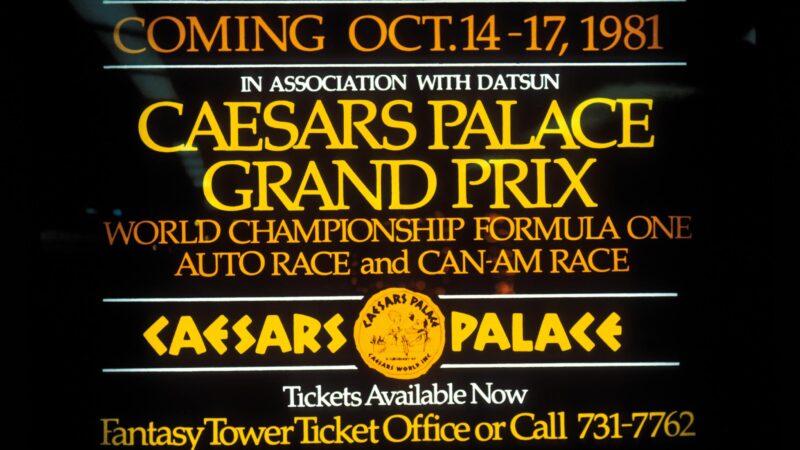

Forty-two years ago, staging a Formula 1 race in Las Vegas was yet another example of Bernie Ecclestone’s fabled ingenuity. By 1981, to be exporting Grand Prix racing to a start-up venue in a dusty car park alongside a casino-hotel in the Nevada desert emphasised that the Little Big Man had broken the grip that the owners of the classic European circuits had held on the governance of the sport only a decade or so earlier.

Not all of Bernie’s wheezes had worked out perfectly. For the French GP he was still persisting with the Dijon-Prenois circuit, owned and built by a one-time all-in wrestler who had financed the project privately. A Bernie sort of guy, you might say, although the ex-grappling star’s habit of settling disputes by punching his adversaries in the throat was hardly the Ecclestone style. Bosses of American gambling joints were reputed to fit a similar confrontational stereotype. What should we expect of Las Vegas, then?

Oh the glamour. ABBA drummer Slim Borgudd was a non-qualifier for ATS. The winner takes it all, eh?

Grand Prix Photo

Representatives of the casino were despatched to an early season event to reassure the media. Most of us having seen The Godfather, we trepidatious scribblers were half-expecting gents in dark glasses and silk suits. Instead, an affable pair of Anglos in comfortable slacks turned up to declare that the casino business in Vegas was now on the level. Silly us for imagining anything different.

The only hint of anything felonious was their insistence that Caesars Palace should be written without the possessive apostrophe, this being an atrocious crime against the conventions of correct English. All very soothing, though, for those of us who set off for the race that would decide the 1981 Formula 1 world championship.

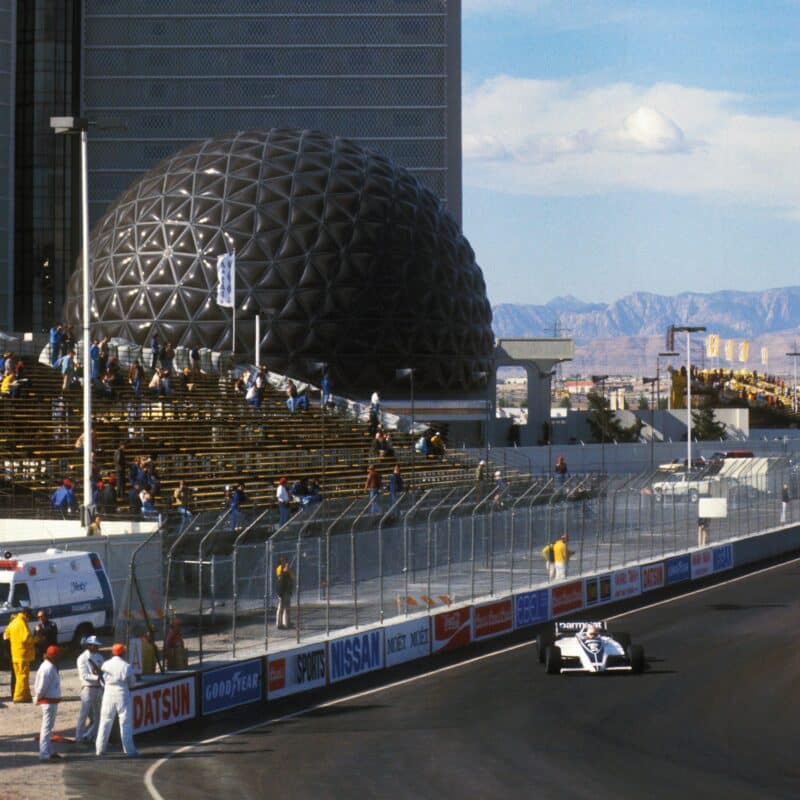

With no disrespect to the fine people at, er, Caesars, I think it is safe to say that their temporary circuit, running between featureless concrete barriers, presented minimal challenge and even less glamour.

One of my duties at distant races in those days was to shoot off a couple of rolls of black-and-white film on Friday and get them back to London overnight, to complement the expensive agency photograph that would illustrate my report when I telexed it to the offices of my employers’ weekly magazine on Sunday evening. (Telex? If you’re under 40 ask your grandfather).

Nelson Piquet passes a near-empty stand.

Grand Prix Photo

When practice started on Friday morning, we photographers discovered that for some reason access to the centre of the circuit was barred. Representations were immediately made to the promoter, Chris Pook, who promised to sort things out. The Friday afternoon session (first qualifying in those days) was just about to begin when, by chance, I ran into Pook at the edge of the circuit. He confirmed that the infield was now “legit” for lensmen and he even had a word with a marshal to escort me across the track.

As a result of this last-minute move, I was the sole photographer working that session from the inside of the circuit. Also present were a number of policemen, all looking a bit lost. One of these cops soon approached me to inform me that I was working in a forbidden area. Not so, I told him, that restriction had now been countermanded, and I continued working. Very soon I had two more policemen tracking me and demanding that I instantly cease operations.

My entreaties, and my insistence that the word had come direct from none other than Mr Pook, had no effect. When I attempted to move away, they pounced upon me and clapped me into handcuffs. This would prove to be an unwise move.

Event poster

Grand Prix Photo

My plight quickly came to the attention of colleagues working on the other side of the track. By the time the session was over and I was being escorted by my new police chums to a temporary lock-up underneath the casino, the word was out that The Dude had been arrested. The reaction in the press room, I would discover, had been a mixture of hilarity and mild concern. Some suggested that I was a bumptious clever-dick who probably deserved to spend a night in the hoosegow, if only for his appalling choice of headgear (see previous page). Others were concerned for their own freedom to work unhampered by overweight men in uniforms who clearly did not understand racing but also happened to be carrying a lot of personal artillery.

Fortunately for me, one of the people who endorsed the latter view was none other than the choleric Frenchman Jean-Marie Balestre, president of the FIA. Widely regarded as a figure of fun whose unpredictability often ended in embarrassment, Balestre did not command universal respect. On this occasion, though, his response was immaculate – at least as far as I was concerned – for he demanded my immediate release.

When the cops hesitated to let me go, a furious Balestre upped the pressure on them by calling an impromptu press conference at which he cited a long-standing FIA rule which specifically prohibits police officers from being involved in the administration of the sport. Their presence at the circuit as self-appointed marshals clearly usurped the majesty of the Federation. Unless Monsieur Doodson was released, he thundered, the Las Vegas Grand Prix would lose its world championship status and all the teams would be forbidden from taking any further part in it.

Basic pits for Ferrari

Grand Prix Photo

Your correspondent, still under guard in the bowels of the Caesars (no apostrophe) Palace hotel, only became aware that something significant was up when my cuffs were unlocked by a cop whose mood had suddenly gone from stern to worried. There was a cheer from my fellow hacks when I returned to the press room.

“The reaction in the press room had been a mixture of hilarity and concern”

The incident was welcomed by colleagues. They, and the photographers who had been close enough to shoot pics of me in irons, were particularly delighted because now they had something more interesting to offer to their editors than humdrum images of racing cars dodging between concrete blocks.

How about a flutter on Alan Jones to win in the ‘car park’ – at 10/1? Nah…

Grand Prix Photo

The best stories, though, had to wait for the specialised monthlies. In Road & Track magazine, Rob Walker gleefully recounted my misfortune, alongside a separate lavishly illustrated sidebar by my former flatmate Pete Lyons, who wrote that I had been arrested. This raised the hackles of the Las Vegas chief of police, who sent a carefully worded response to the effect that, “Mr Doodson was not arrested, he was merely taken into custody.” While this was technically true (I had not been read my rights when Officer Chubster clapped me in bracelets), the significance of a senior cop writing so punctiliously to the Editor of R&T had not occurred to me.

All these years later, do I have any regrets? You bet I do! If only I had reflected more profoundly on the consequences for my professional image of being illegally detained. Alas, those deeper implications of the chief’s ‘correction’ were lost on me. A New York lawyer later informed me of the implications for those cops if I had chosen to sue.

Mon sauveur! Doodson with president Balestre at a slightly damper Zolder, 1980

Mike Doodson

Just think of it: denial of rights, denial of work, unlawful detention, professional humiliation! The damage to my reputation! Had I been more awake, I’d have pressed my case. The mere threat of engaging the LVPD in court would surely have resulted in an offer of damages, and you don’t have to be an expert in transatlantic litigation to know any compensation would have been substantial.

For the record, that trip was financially unrewarding in other respects. Before departing I had primly resolved not to bet so much as a nickel in Vegas, a promise which proved difficult to uphold when I saw the odds that the local bookies were offering for the race. Alan Jones was carelessly assumed to be a backmarker, at one stage being listed at 10-1. Nevertheless, I held firm. You can imagine my chagrin when Jonesy led every one of the 75 laps to win by a comfortable 20 seconds.

Jones leads Gilles Villeneuve and the rest at the grand prix.

Grand Prix Photo