Online auction saleroom goes viral

As this issue goes to press, many people involved in the classic car business would ordinarily be resting up after the madness of Monterey Car Week in California — but…

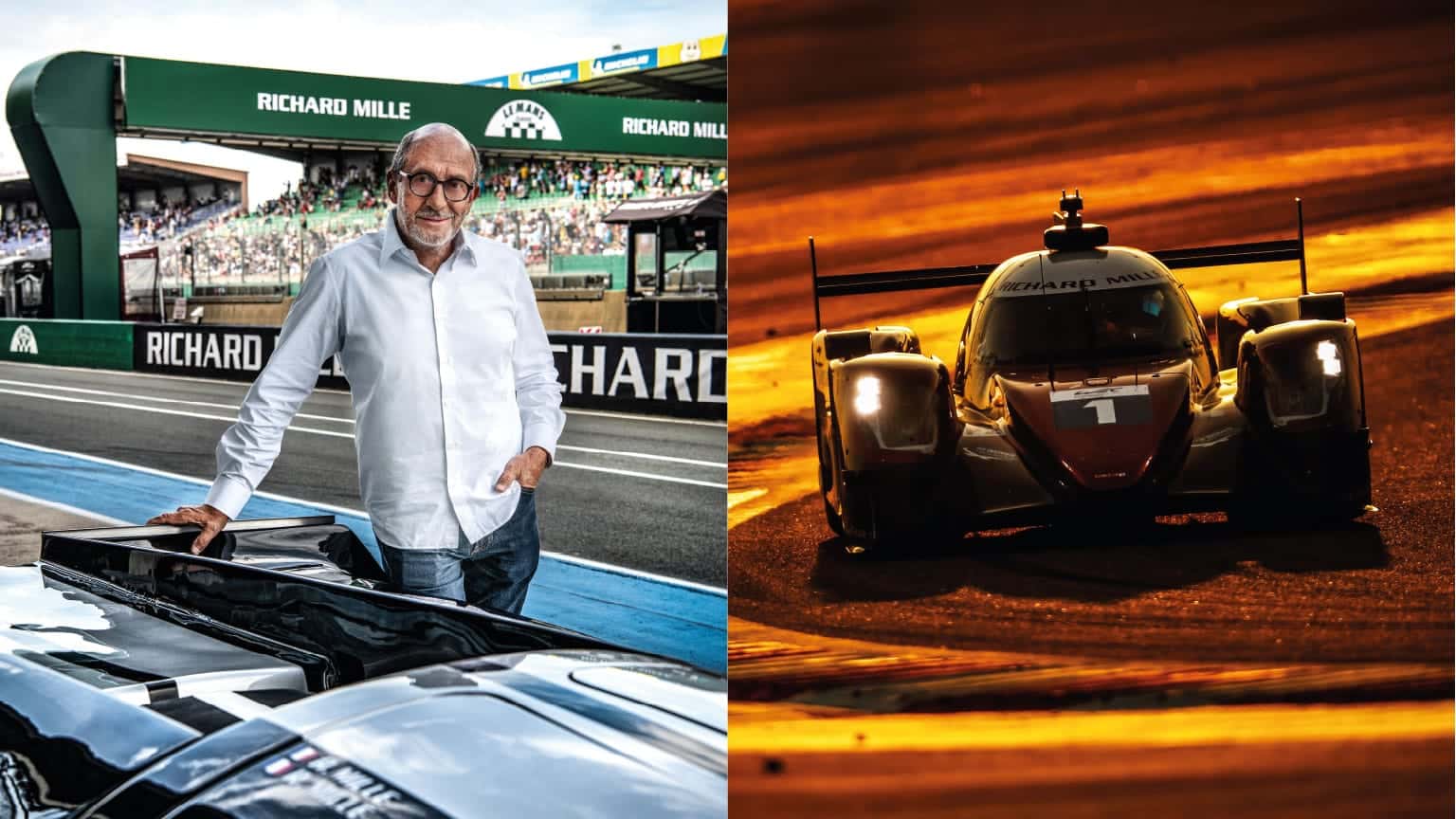

PHILIPPE LOUZON, DPPI

You’ll know the name. How can you not? Richard Mille branding seems to pop up just about everywhere in motor sport these days. Yet the man behind the Swiss luxury watchmaker is more of an enigma, at least beyond the confines of paddocks and boardrooms. Which is a shame, because Richard Mille is an easy man to like if you get the chance to spend some time in his company – and he also happens to be a figure of significant influence in our world. We should probably know him better, because Mille is more than an enthusiastic commercial sponsor of Formula 1 and sports car teams, plus events such as Le Mans Classic. He is also playing an active role in shaping the future of motor sport, specifically in an arena he holds dear to his heart: the Le Mans 24 Hours itself.

Since 2018, Mille has served as president of the FIA Endurance Commission, working to a mandate to lead the World Endurance Championship, which has Le Mans at its core, into an exciting new era. That means he’s one of the architects behind the Hypercar revolution that has convinced major car manufacturers to flock back to sports car racing, on the promise of rules parity and realistic budgets that offer value for money. It’s not limited only to the WEC, of course, but also in the US IMSA series too, thanks in part to the long-awaited accord that is flourishing between the two series. Mille carries a share of the responsibility for convincing Ferrari and Peugeot to join Toyota and Glickenhaus in Le Mans Hypercar (LMH), and has contributed to the amazing influx into the new-for-2023 LMDh parallel category: deep breath… Porsche, BMW, Acura, Cadillac, Alpine, Lamborghini and potentially more, will rock up either next year or in 2024. It has the potential to be fantastic, a match perhaps for 1980s Group C, even a throwback to the endurance racing heyday of the 1960s.

In 2021, Richard Mille entered an all-female team at Le Man

Getty Images

After a gap of six years, Porsche will return to endurance racing’s top table in 2023 with its 963

Porsche

But before we get into all that, what about Mille’s own car collection? It’s known to be significant in size and scope. Richard, please, tell us more… “It’s compulsive, eh?” he says with a smile. “I have a lot of Formula 1. For me, they are pieces of art.” They’re not all in one place, of course. Imagine that! “I need room,” he chuckles.

The F1 cars span the 1950s to the mid-1990s, after which they become technically more complicated to maintain and run. “F1 cars of the 1970s were a fantastic era because you had a lot of innovation, the regulations were more open, so you had a lot of different engines and so many different shapes,” he says of his favourite time.

“This is what we wanted with the Hypercars, so you could distinguish one from the other. The problem that we had with modern F1 is the cars were all made by computers: take the paint off and you are in trouble… In Hypercar it was important to offer rules that allowed for strong identification. The Peugeot doesn’t look like the Porsche, which doesn’t look like the Glickenhaus, which doesn’t look like the Toyota and so on.

“What I love in my collection is to have so much diversification. I have, for example, nearly all the four-wheel-drive F1 cars: the Cosworth, BRM P67, McLaren M9, Lotus 63, the March six-wheeler…”

Born in Draguignan, in the Var region in the south of France in 1951, Mille is a true child of the 1960s. He recalls a poster on his bedroom wall of Jochen Rindt in a Brabham BT18 at Pau, and carries blessed memories of watching Peter Schetty racing Ferrari’s 2-litre 212 E up Mont Ventoux during his domination of the 1969 European Hillclimb Championship. “The first grand prix I saw was Monaco in 1967, a bad start – the day Lorenzo Bandini died,” he says. “I was always totally cuckoo about racing. Even my watches are influenced by cars and their technology.”

“There is no reason why endurance in the years to come will not be as successful and profitable as F1”

His career in watchmaking began with local company Matra Horlogerie in 1974, but it wasn’t until 2001 that he achieved a long-held ambition to strike out under his own name, founding Richard Mille with his friend Dominique Guenat. For the past two decades, the company has established its place at the sharp end of the rarefied world of eye-wateringly expensive luxury watches, with a range of timepieces instantly recognisable for their shape, design and focus on precision technology. The parallels to F1 are all too obvious.

But his direct experience of motor sport, beyond owning and driving an incredible roster of cars, is limited. How has he ended up in an influential position of governance? “It was a request from Jean Todt,” Mille explains. “He asked me about 10 years ago and I declined because I was so busy. I told him, ‘Jean, I wouldn’t be capable to do that.’ His answer was a typical Jean Todt answer: ‘I am more in a position to tell you whether you are able to do this or not. I am more informed than you!’ A few years later he asked again and I said yes.”

Mille with former FIA president Jean Todt

Getty Images

Mille with Get Lucky vocalist Pharrell Williams on a star-studded Miami GP grid in May

DPPI

Mille took up his presidency at a low point for premier-level sports car racing. Costs had spiralled out of control in the technically advanced sphere of hybrid LMP1, with Toyota the last marque standing in the wake of withdrawals from first Audi and then Porsche. His friend had presented him with “a real challenge”. “Four years ago nobody would have put a penny on our head, because we had only Toyota,” he says. “I spent a lot of time trying to convince Peugeot to come. My friend Carlos Tavares [CEO of the Stellantis Group which owns PSA] is very keen on budgets, so I said if Carlos Tavares agrees it means we are reliable. At the commission I insisted we list the budget line by line: the tyres, the gas, the engine, the chassis, as many details as possible… We were coming from an era where the yearly budgets were in the hundreds of millions. When we said you could do a season for between €20m and €30m everybody thought it was a joke. But we have proved it was realistic.”

A Le Mans classic at the Le Mans classic, 2016

Alamy

Todt’s choice of president was astute. An outsider on the inside, his prominence in the watch world means he is well connected, he knows and understands motor sport – and people like him.

“What I love is to transform everything I do into business,” says Mille, before making a big claim. “There is no reason why endurance in the years to come will not be as successful and profitable as F1. There is no reason. But I always say the first stage of the rocket launch was to bring all the OEMS around to the track. The second part was to develop this category and to have a real world championship, not only Le Mans. We say sometimes that Le Mans can be the tree that hides the forest. We have to work to develop this world championship.”

As successful as F1? Really? He’s genuine about that. “My biggest objective was to bring younger generations to the track,” he expands. “Endurance was getting a bit old, the spectators were more in their forties and fifties. With Hypercar we have the tools to bring in the young generations, because on video games and in their minds these cars are their dream. Hypercar is closer to street cars than F1, so we have all the ingredients to bring the public to the track. You can imagine what will be the grid next year for the 100th anniversary of Le Mans, but also in 2024 and beyond.” He lists that roll-call of manufacturers. “It’s fantastic and a grid that never existed in the past. Like Le Mans in 1966, it will become legendary.”

Richard Mille watches has been a partner of the Chantilly Arts & Elegance automotive competition since its first edition in 2014

DPPI

The accord between the FIA’s WEC and IMSA was key to opening the floodgates and Mille is rightly proud that two rulebooks – LMH and LMDh – will co-exist. Whether they do so in harmony remains to be seen. “Today the [manufacturer] boards cannot afford to develop a car for IMSA and a car for the WEC,” he says. “It is impossible, we have to forget that. Luckily we have a fantastic relationship with IMSA, with Jim France and John Doonan. They are very open and we were very lucky to achieve this agreement, on which we had to work a lot. And it is not finished, because every day there are topics that are rising, such as Balance of Performance. But the spirit is there and it’s a very good spirit.”

Ah, Balance of Performance. BoP. The artificial and often controversial foundation of so much modern motor sport, particularly in the endurance arena. Whatever your view, without BoP the mass of makes and variety of car concepts promised by Hypercar just wouldn’t be possible. But Mille is under no illusions about the challenges to come.

“We have a lot of pressure, you can imagine,” he says. “Frankly it is not working well in GTE. It was in the past, but recently it has not been very successful. But we are working very hard to have a BoP that is as comprehensive and simple as possible. There are so many parameters and we have in front of us armies of engineers, all of them wanting to win. They are fierce competitors and just like in F1 they will find and do everything within the regulations to be successful. BoP is not simple, but we cannot escape from it. I know many people are against it, but we would not have all these makes and factories on the track without it. It is compulsory because it is the only way to cut the budget. You can spend €80m developing a car and you won’t have an advantage over somebody who spends €20m, because the BoP will penalise you.”

Branding of the watchmaker is a regular sight in racing – seen on Lewis Hamilton’s GP2 racer in 2006

Getty Images

The problem, he pinpoints, is second-guessing what is and isn’t genuine pace. “It’s very difficult to distinguish sandbagging and performance,” Mille acknowledges. “This is a problem we have to cope with. We have to find a system where we don’t have so many parameters, but all competitors must be in a window that gives them the possibility to win.”

At the Goodwood launch of Porsche’s 963 LMDh contender, the company’s sports boss Thomas Laudenbach echoed that sentiment. “I’m happy to look at it as a challenge and as a chance,” he told Motor Sport. “As you say, if we didn’t accept BoP I don’t think we would ever have what we are facing now. If we want to have this convergence [of regulations] and cost control we have to accept BoP. Now we have to get it right. We have a certain trust in the sanctioning bodies, otherwise we wouldn’t participate. But to me every competitor has a responsibility to give his contribution. We have it in our hands together to get it right so that everybody who comes to race can say, ‘I had a fair chance to win.’”

“With Hypercar we have the tools to bring in the younger generation”

Altruistic stuff. The trouble is Laudenbach, Mille and everyone else with skin in this game knows that high-minded bigger-picture perspectives mean little to competitive, blinkered racing teams. Is this really going to work? “We cannot save everybody,” Mille admits. “If you are too far from the window [of performance] we can do nothing. But we must be sure that we give spectators very good battles. We want to avoid promenades, as we have had in previous times in F1, with long cycles where it was once Ferrari winning, then Red Bull, then Mercedes. What people have to understand is the BoP is not about being drawn to the bottom. It is not a contradiction to performance.”

Richard Mille Racing Team’s drivers have included 21-year-old Lilou Wadoux

DPPI

Richard Mille Racing Team’s LMP2 Oreca 07 has been involved in this year’s World Endurance Championship

DPPI

Beside his governance role, Mille’s watch brand has associations in F1 with both Ferrari and McLaren, and a dual interest in sports car racing as a team owner in LMP2. The Richard Mille Racing Team, run by French sports car powerhouse Signatech, was originally established for all-female driver line-ups, but it changed tack this year by calling up only one woman driver, Lilou Wadoux, who was teamed with Charles Milesi – LMP2 Le Mans winner and WEC champion with WRT last year – and Sébastien Ogier. Since Le Mans, where the trio finished ninth in class, the eight-time World Rally champion has stepped down, with the experienced Paul-Loup Chatin replacing him. Given Mille’s role in the new era, it’s easy to picture his team moving up to the LMDh class as a customer – so does he want to win Le Mans himself?

“The biggest objective is to bring girls to the top, to podiums,” he says, playing down such ambitions. “The problem we face is that there is not a complete reservoir of girls [to draw from]. It’s a work in progress.” He believes endurance racing is the perfect platform to promote women in motor sport. “We also want to change the image that women don’t know how to drive or are not interested in the mechanical aspect, which is wrong. This year Lilou is learning extremely quickly, she’s very reliable, she’s very quick. We changed the philosophy from last year of having three girls because we decided it would be interesting to compare one to Charles, who has been a Le Mans winner and world champion, and also to Séb Ogier who is coming from rallying, a different discipline and universe. As we do in watches, I always like different worlds and cultures to meet.”

Back to the bigger picture. Long-term, Mille recognises and accepts endurance racing’s potential as a platform for alternative power, most obviously hydrogen and the H24 programme that is already well underway. He’s encouraged by the “paradox” that while motor sport is perceived to be “politically incorrect” it remains as popular as ever, although he also reveals a disenchantment with Formula E, a series he supported from its foundations in 2014. “As a brand, we didn’t continue with Formula E” – Richard Mille was previously a sponsor for Renault e.dams and Venturi – “it was very disappointing.”

“We must be sure that we give spectators very good battles. We want to avoid promenades”

Mille straddles different worlds, both in business and in his passions. As his collection of cars proves, he’s in a privileged position to indulge his petrolhead compulsion, but at the same time refuses to live in the past. “Of course motor racing has to adapt, in terms of sustainability with e-fuels, with the management of longer lasting tyres and the development of hydrogen power,” he says. “It’s interesting at the moment as we accompany racing into this new era without losing our soul, without losing what makes us dream and happy. It’s like a baby that has to be taken care of.”

Wealthy, successful and a friend to the powerful, Mille somehow comes across as remarkably normal and grounded. There’s a twinkle in his eye, and a smile and a chuckle is never far away. You can see why Todt recognised he’d be a great salesman for modern endurance racing. “We have a mission, Damien! Ha, ha!”

And the car collection: at the risk of blooding the water for dealers and auction houses… is there anything he doesn’t own that he still desires? “Still many, still many,” he says with a smile. “It is compulsive and I haven’t found a cure for that!”

Richard Mille deals in time and at 71 he should still have plenty left. There are always more cars to buy, but you sense he has at least as much to give back to his beloved sport as well.