Secrets of the Steering Wheel Club, the '60s bolt hole for racing drivers

What's the collective noun for racing drivers? You'd have needed it in the 1960s to describe the denizens of this comfortable Mayfair bolt hole. Gordon Cruickshank explores the club, its members, and what happened to the magnificent collection once on display there

Richard Atwood, left, and Hans Herrmann, right, pose with Stirling Moss and Rico Steinman on adding their 1970 Le Mans-winning wheel to the club display

“It was a great club. I’m amazed somebody hasn’t restarted it.” That’s Sir Jackie Stewart’s take on the Steering Wheel Club, Mayfair home from home for racing drivers. In the 1960s and into the 1970s everybody went there, including international grand prix drivers when they were over here; with a busy bar and restaurant it was a social hub, and in an area packed with drinking holes it stood out for the decorative feature that gave it its name – racing car steering wheels.

Contributed as a matter of pride by drivers and teams, dozens of wheels decorated every wall in the bar; wood and leather rims held by Hawthorn, Fangio, Clark, Hill, Brabham, Brooks, Hunt – not to mention the crumpled one that formed the handle to the phone booth, retrieved from Innes Ireland’s Lotus 19 wrecked at Seattle in 1963. Many were from winning machines – Aston Martin‘s victorious DBR1, Clark’s ’63 championship machine and his 1965 Indianapolis winner, Hill’s 1962 title car, the 1970 Herrmann/Atwood Le Mans Porsche 917 victor, Cobb’s Railton LSR car, Parry Thomas’ Babs. Not to mention helmets, goggles, banners and trophies from throughout the sport’s history. And in 1988 when the club folded – they all vanished.

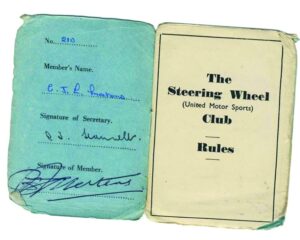

Morgan was a major figure in the sport in the Fifties: clerk of the course and starter for all five Aintree grands prix and secretary of the BARC, while co-founder Desmond Scannell had a similar role at the BRDC. It was 1946 when they found a small flat in Brick Street, Mayfair and opened the United Motor Sports Club. In the economic shadow of WWII they had to install utility furniture, with air raid shelter bunks for seats, though a bar designed by Anthony Heal of the smart Tottenham Court Road furniture store added style. Thanks to the co-owners’ connections it soon became a welcoming base for drivers, constructors, owners, organisers and journalists. And for the BRDC, whose affairs were run from a small back room. It wasn’t long before those wheels began to decorate the walls, making it clear who this place was aimed at. It wasn’t always demure; some happy members set a world record for the number of people perched in and on a Messerschmitt Kabinenroller, respected writer and commentator John Bolster riding shotgun in the fresh air.

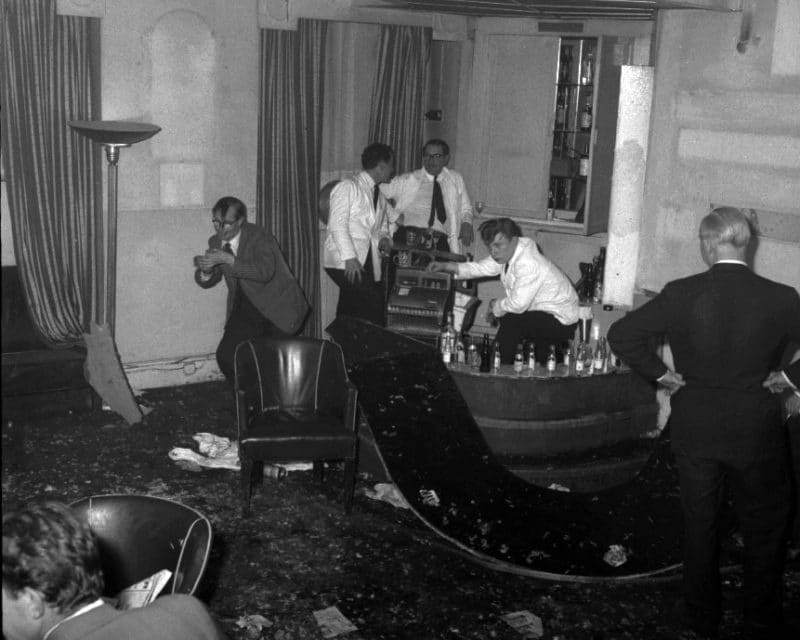

Jack Brabham pulls the plug in the doghouse during the riotous night that brought the end of the Brick Street premises, while Jim Clark watches holding a stuffed pheasant and Graham Hill holds his head

In 1956 Morgan bought out Scannell, and by 1963 the expanding club needed a new home. It moved to an 18th-century building (once the Sun Inn and before that a corsetière, which Grant jokes is code for a brothel) in Curzon Street by Shepherds Market, taking over two floors, reached by a narrow staircase behind a nondescript doorway. Unlike today’s whippet-thin athletes, the era’s racing drivers knew how to party and had a riotous last night at the old place. “All the drivers went,” says Ian. “The bar was ripped out; the place was trashed.” Luckily the bar counter was rescued for the new premises.

Though colourful and lively, the Market was a raffish, even seedy pocket – dubious types hung around and ‘models’ occupied half the flats. Chic it was not – London clubland, yes, but a very different sort to grand St James’s nearby. Still, it was central, and soon every driver wanted to be a member of the Wheel.

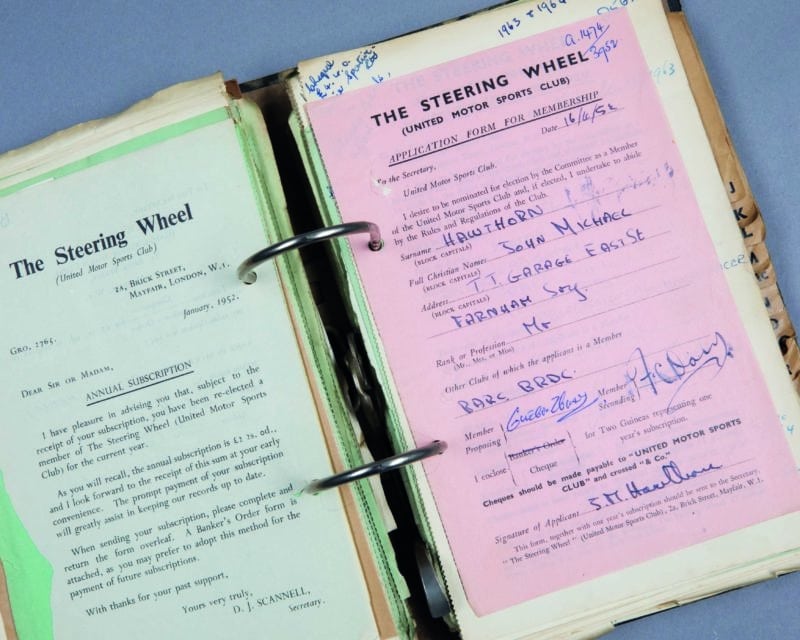

John Michael Hawthorn’s application for 1958 (membership cost two guineas)

Last night at Brick Street, as the bar is literally ripped apart

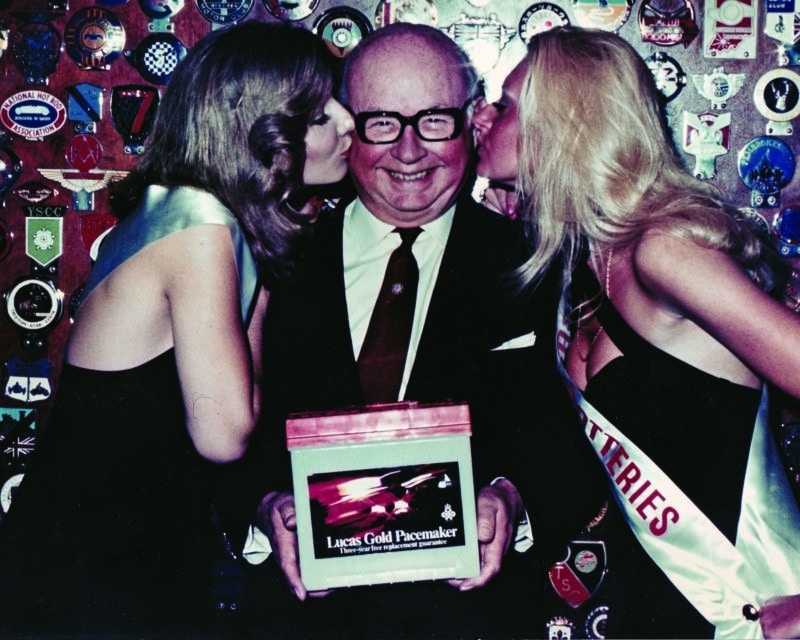

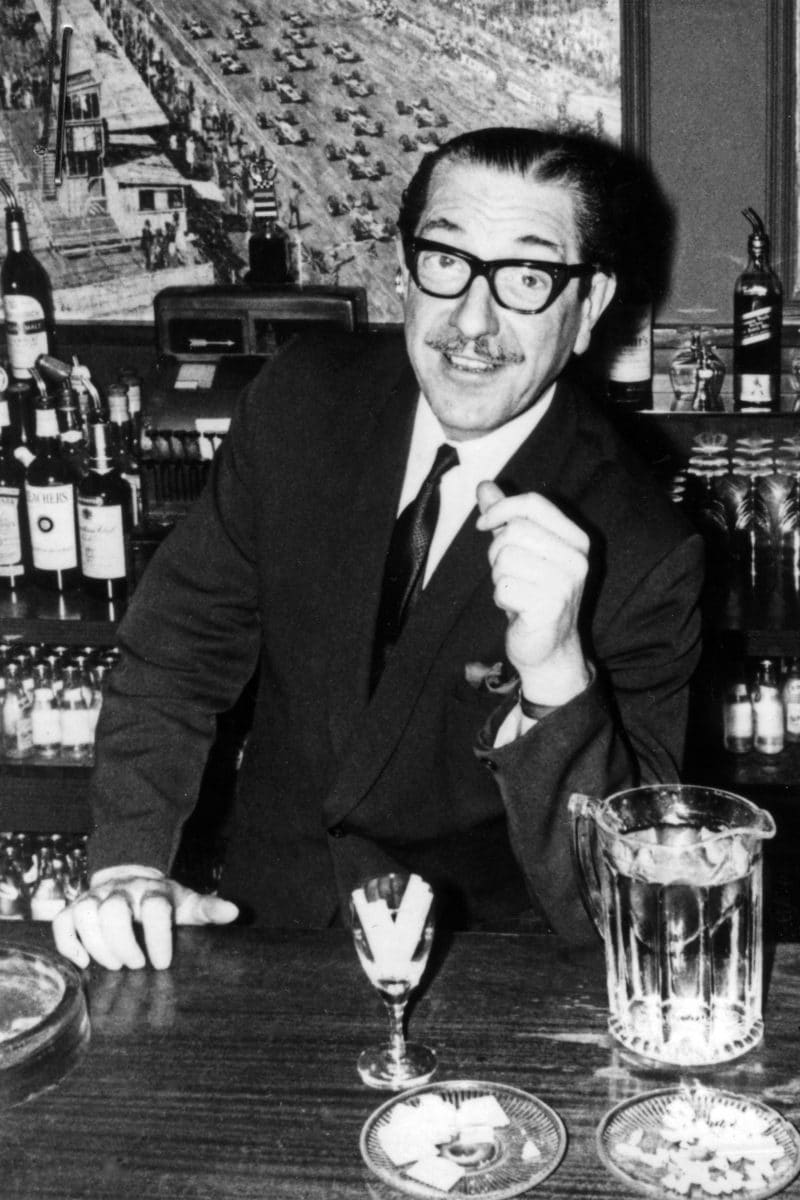

John Morgan watching Le Mans on screen below a painting of the start of the 1957 British GP – Stirling’s W196 wheel from that Mercedes 1-2 was elsewhere on the club walls

Our own Nigel Roebuck recalled on his first visit there seeing Autosport’s Gregor Grant at the bar talking to Innes Ireland, “…and my cup indeed ran over”. Living nearby, Stirling Moss often looked in, while a then unknown Graham Hill would famously nurse a half pint at the bar hoping to make useful contacts. He wasn’t alone: Howden Ganley, later to be a grand prix driver himself, recalls “It was the custom to join the club. My mate Bill Gavin took me there and introduced me to the man who owned Falcon Shells, telling him I was the fastest guy on four wheels and should race one of his cars. He took me on and I was able to build a new GT515 to race. So the Wheel worked for me!”

“This membership file,” says Keith Grant showing me the paperwork, “contains at least 100 racing drivers, maybe 20 grand prix drivers and several world champions”.

Keith joined in 1963 – he raced in long-distance sports car events in Brabhams, Chevrons and an Elva-BMW up to the 1970s – and got to know the clientèle. With so many drinking clubs roundabout, all sorts would drop in: “Sportsmen, TV people, villains, coppers… Peter Ustinov was a member. The great train robbers used to come in – I knew Roy James well. And David Blakely, who was shot by Ruth Ellis, was a member.” For a time Ellis (later hanged for the murder) managed The Little Club, almost opposite the Wheel, known to be a venue for secretly gay high- profile figures, gangsters and shadowy men who “worked for the government”. (In Ruth Ellis – my sister’s secret life, Ellis’s sister claims the Steering Wheel Club was also a hangout for the secret services and Stephen Ward of Profumo scandal fame.)

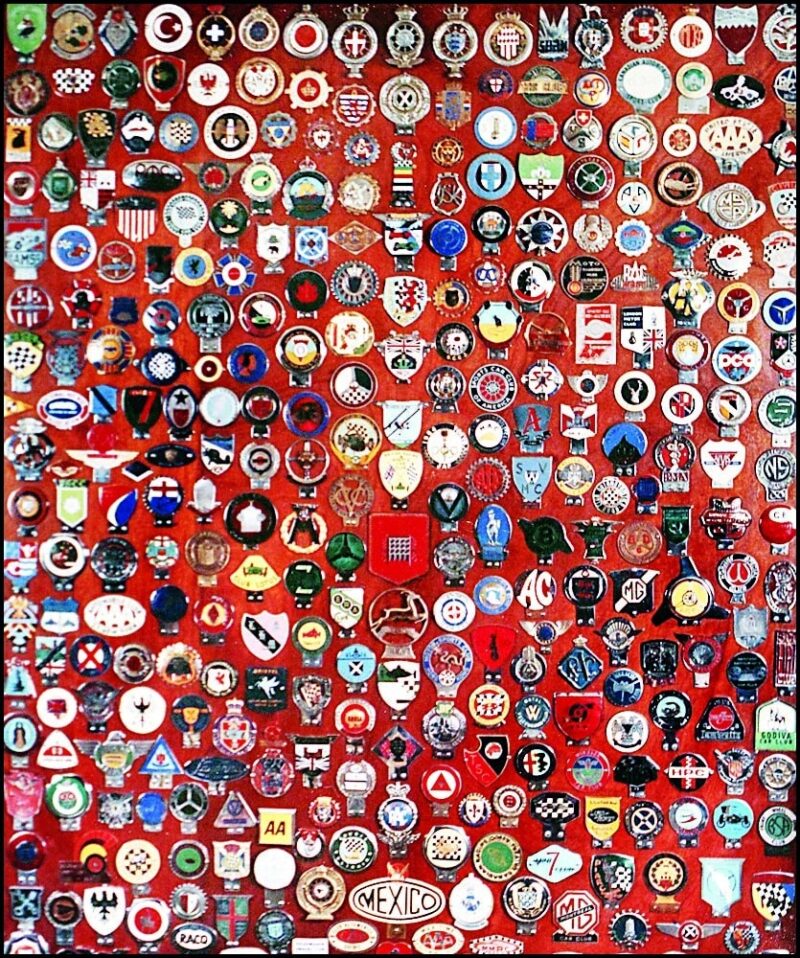

Still, racers outnumbered racketeers. The Wheel was a respectable club, traditional in décor, with sofas and armchairs and sporting fine racing pictures by the likes of Dexter Brown, Gordon Crosby, Peter Helck and Roy Nockolds. An inventory from 1979 lists these along with the wheels, helmets, goggles, the club badges, the trophies. The value even then was listed as £20,000.

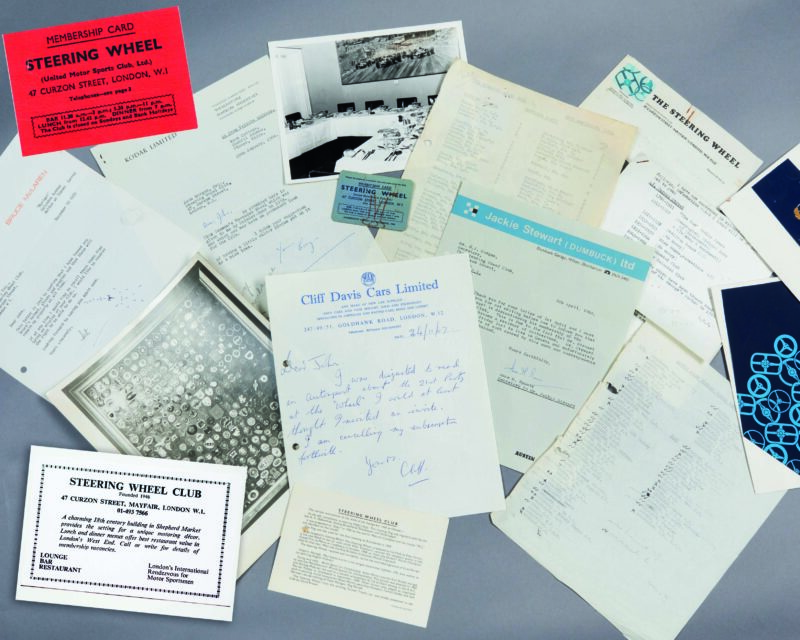

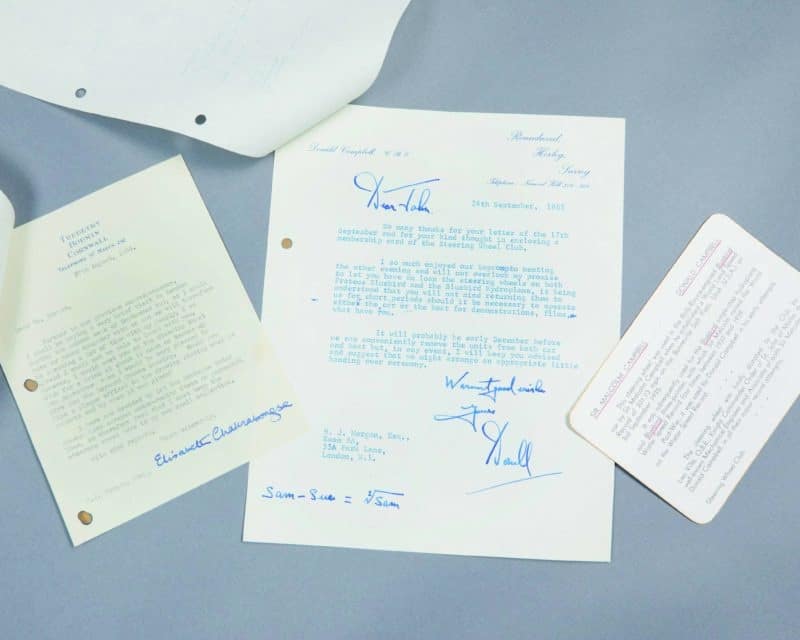

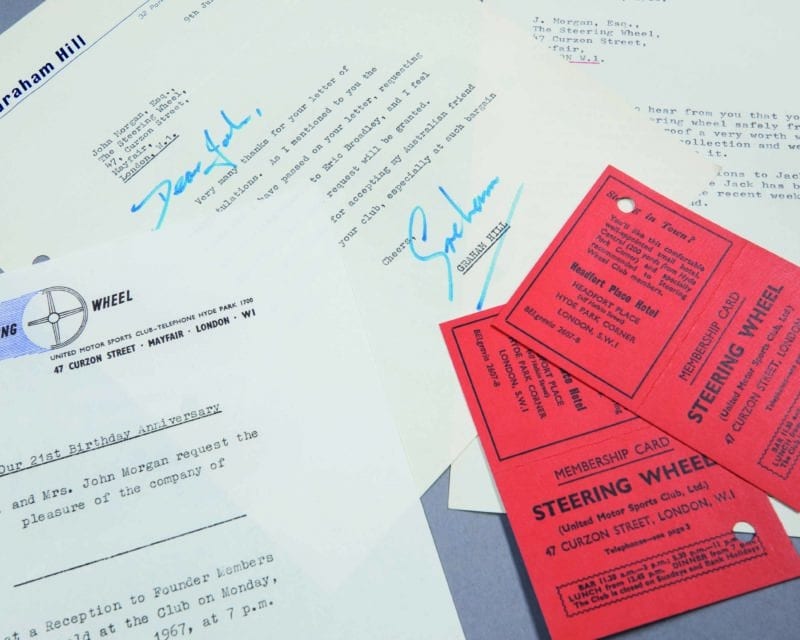

Assortment of club records and correspondence recently discovered by Keith Grant, including samples of tie design proposals, a photo of the meeting room, letters from Jackie Stewart and a note from a “disgusted” Cliff Davis (previously a club regular) resigning his membership as he was not invited to the 21st party

Ian fills in the picture of his uncle John Morgan and his wife Haysie, the other club cornerstone. “A shy man; very good at organising publicity events at the club – presentations and the like – but in the photos he’s always standing back. He was genial but always calm. In an emergency he would deal with it without fuss – an ideal organiser.

Morgan retained a loyal staff: for years bow-tied Frank Vent ran the bar, his brother Ernie the restaurant upstairs while Peggy Sandberg was maitresse d’. Any event at the club was a direct route to the racing press, since journalists like Gregor Grant, John Bolster and John Blunsden were bound to be there anyway; there are photos of Tony Brooks accepting a Ferrari wheel from the scuderia’s sporting director Romolo Tavoni, BP adverts featured the club, and it was regularly mentioned in press gossip. The committee room was well used, by the BRDC, other motor clubs, even helicopter and powerboat clubs. Well, it started as United Motor Sports. Other sportsmen came in, too: on party nights you might see footballers Jimmy Hill and Bobby Moore. And it was the base of the Doghouse Club, the fundraising group run by wives and girlfriends of the racing world who ran a celebrated annual ball as well as childrens’ parties.

John and Haysie pose with the Chapmans, Jim Clark and the Brabhams

Steering Wheel Club proprietor and host John Morgan and his wife Haysie show off the cake at the 21st birthday party celebrations for the club, assisted by Denny Hulme and Jack Brabham

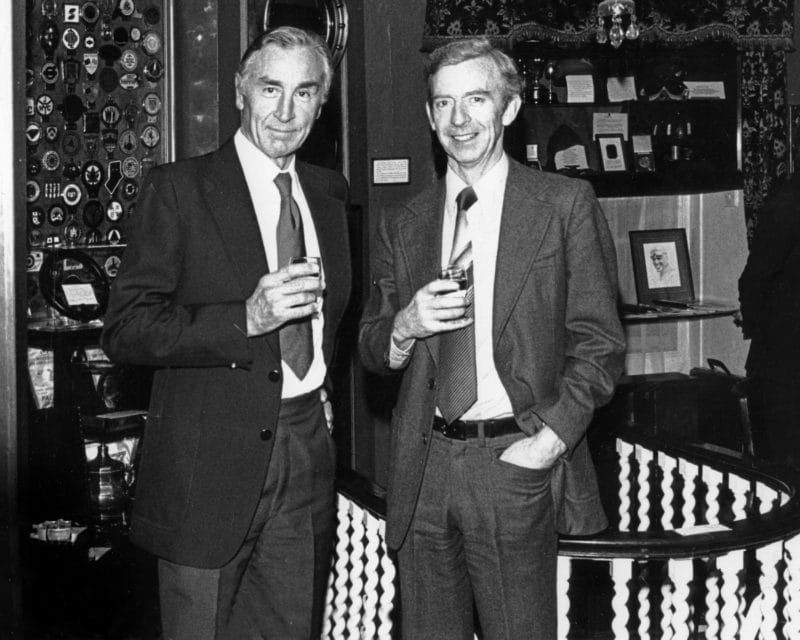

Morgan and friends in front of the badge display

Derek Bell was an enthusiastic member. “We all went there. ‘See you at the club’, we’d say. I’d nip up to London for BRDC meetings and make an evening of it. It was so convenient – Piers Courage, Charlie Lucas, Frank Williams were all in London so we’d meet. There was a great atmosphere; we were fortunate to have it as a base. BRDC meetings at Silverstone never had the same atmosphere.”

Like Bell, saloon racer Dave Brodie recalls the Harrow crowd usually being there, “and of course we behaved impeccably… We went to see our heroes – Moss, JYS, Hill, Brabham, Hulme. We all acted cool but inside I was buzzing with admiration. Graham would gave me great tips, like the best line at Druids – helped me get a load of lap records at Brands.”

Joining a little earlier, Jackie Stewart has equally warm memories: “It was David Murray [the Ecurie Ecosse founder] who introduced me to the club. Everybody was a member. I was in awe of some of the people in my early days – Jimmy Clark, Duncan Hamilton, Tony Rolt, Les Leston, Paddy Hopkirk. It was a cosy place, beautifully run. I think there’s something missing not having a club of that nature.”

Juan Manuel Fangio greeting a delighted Nigel Roebuck before their interview

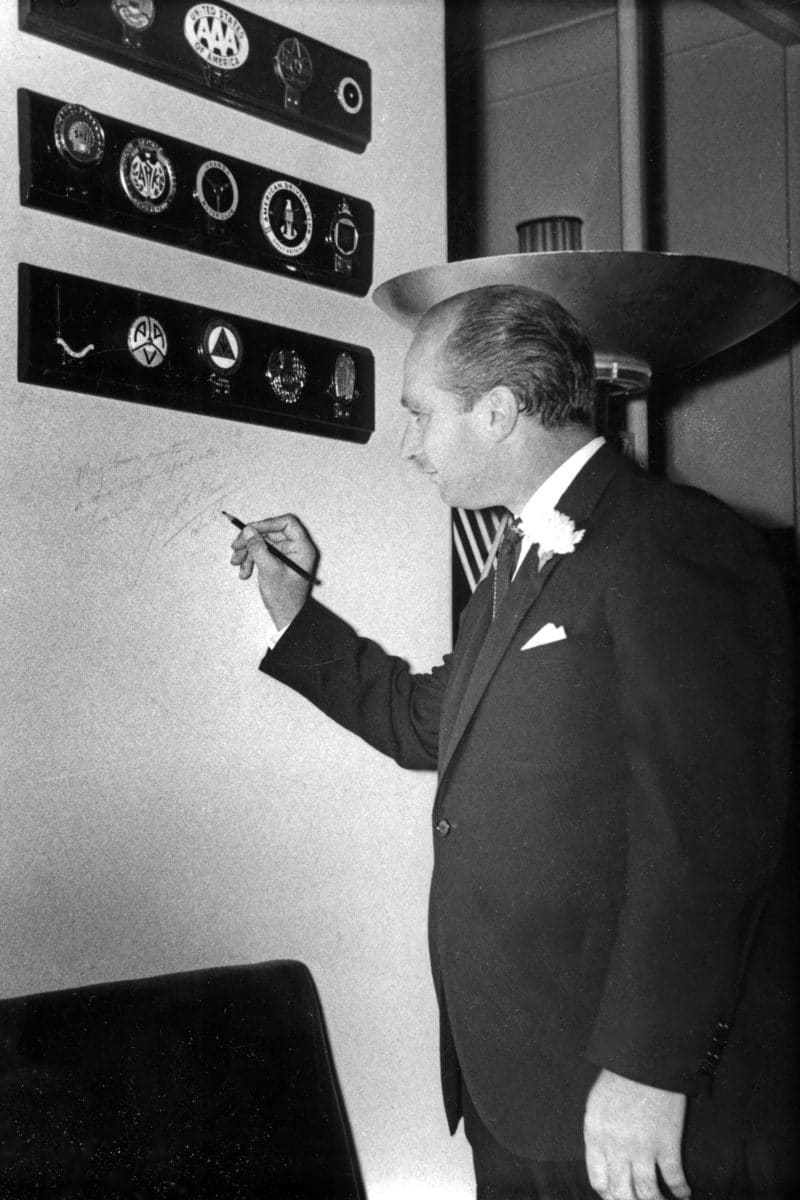

Fangio signs the wall during his 1979 visit

A cheery Frank Vent behind his well-stocked bar at Curzon Street

One momentous day came in 1979, when five-time world champion Juan Manuel Fangio visited, on his way to drive a Mercedes-Benz W125 at the Gunnar Nilsson memorial meeting. Nigel Roebuck interviewed him (writing emotively about the meeting in Motor Sport in January 2001), press cameras popped, and the great man signed the wall of the bar.

But there was other writing on the wall too: the club was losing money, and Morgan wanted to retire. That year he sold to a consortium, and in 1980 Keith Grant was installed as manager. It was a very different era, and Keith is firm: “I don’t want to talk about the consortium. They weren’t motor racing people but they had the money. They let me run the club for a few years, but eventually decided to turn it into a high-class Mayfair eatery. They refurbished it completely, getting rid of the memorabilia which was the club. I said, ‘well, you won’t see me again’, and left.”

That was 1986; two years later the club folded. Ian Macfadyen takes up a sad story: “The receivers went in to value everything and seize the assets, but the premises had been stripped. Some of the stuff must have been sold privately but most of it just disappeared. Bette Hill was furious about the Graham Hill things.”

Various items have resurfaced in auctions since, notably the framed collection of club badges and a few wheels, but the majority has evaporated as completely as Nazi art plunder. With Keith Grant’s very recent discovery of the club records, unknowingly parked in his garage 35 years ago by one of the consortium, the historical loss becomes crystal clear.

Magnificent collection of car and club badges framed and mounted on the walls

Morgan obviously kept all his paperwork – not only letters from the famous members and their signed membership forms but also carbon copies of his replies. Thus, a letter from JYS resigning his membership because of moving to Switzerland; reply from Morgan teasing him that “it’s only a few pounds”. Confirmation from Jim Endruweit that Lotus has indeed sent the wheel from Clark’s ’63 title winner; a thank you to Pat McLaren for Bruce’s helmet, gloves and goggles. A promise from Donald Campbell to loan wheels from both the CN7 LSR car and K7 hydroplane; a note from Teddy Mayer saying ‘Here’s James Hunt’s wheel from the McLaren he drove in Japan’.

To anyone with a feeling for history it’s painful to think of these glorious artefacts being sold off secretly; there’s nothing wrong with their being owned privately (ignoring questions of past donation) but it would be a relief to know where these treasures are – if they still exist.

Thankfully Keith is on hand to distract me with tales from his days at the Wheel.

“I’d not been there long when the receptionist said ‘There’s a bloke called Alan Jones at the door with a steering wheel. Will I let him in?’ He’d just won the 1980 world championship and brought his Williams wheel personally!”

Correspondence from Elizabeth Chakrabongse, wife of ERA and Maserati driver Prince Bira, about donating an original drawing, and from Donald Campbell (typed in his trademark blue) promising to loan steering wheels from his Proteus car and Bluebird hydroplan

Roy Salvadori and Tony Brooks enjoy a glass

Maybe this blank invitation to the club’s 21st was the one that should have gone to Cliff Davis?

By this era there were fewer GP drivers and a more general crowd at the bar. Keith remembers the New Zealand All Blacks coming in, indulging in drinking games with Tony Lanfranchi, Gerry Marshall “and other nutters”, and a parachuting-from-the-sofa competition with some real-life Paras. When somebody poured beer down the piano, “Jackie Epstein sprayed it with WD-40 and it was fine!” He tells lurid tales of the local mob trying to sweeten him with presents of cars and flats: “Luckily the West Central Police guys used to have a couple of beers in the afternoons, so I told the gangsters they were being watched and they disappeared.”

Ken German was a young police officer then, and confirms: “The CID were always welcome there. One night we were outside in our unmarked Jaguar Mk2 waiting to nab members of a local protection racket. After a while a rather animated but friendly Innes Ireland came out with a tray of drinks for us and asked if he could drive our car.

“He wanted to drive a police car through London at speed using the bell and horns and blue light, ‘and perhaps squeeze a few friends in as well, please?’

Keith is a jazz enthusiast too, relishing nights when racer and jazz legend Chris Barber would play impromptu, sometimes with a scratch band of racing aces. “Musicians from the National Youth Jazz Orchestra would drop in and play for a pint. Late one night some other blokes came up and joined in and we thought ‘they’re good!’. It was the Woody Herman band who’d been playing at Ronnie Scott’s nearby. We had the whole band playing blues at 3am!”

There were great times at the old Wheel in its four decades. Could something similar thrive today? Perhaps, perhaps not; racing drivers mostly live a very different lifestyle nowadays. Latterly racer and auctioneer Robert Brooks bought the club name and used it to brand VIP hosting at Goodwood Revival, but with his death the name is in abeyance once more.

Meanwhile some of motor racing’s great treasures are out there somewhere, and Keith Grant holds signed evidence of their provenance. Look at Ian’s inventory; imagine the value of the Vanwall wheel Brooks and Moss gripped in the 1957 British Grand Prix, or a polkadot scarf that fluttered round Tim Birkin’s neck, or a Mercedes wheel autographed on its four spokes by Rudolph Caracciola, Manfred Von Brauchitsch, Hermann Lang, Max Sailer, Alfred Neubauer and Rudolph Uhlenhaut. Perhaps someone has inherited that Le Mans-winning 917 three-spoker, not knowing its story? Can anyone re-join the dots that lead back to a great hub of racing’s past?