Knowing Michael Schumacher: cracking the Enigma Code

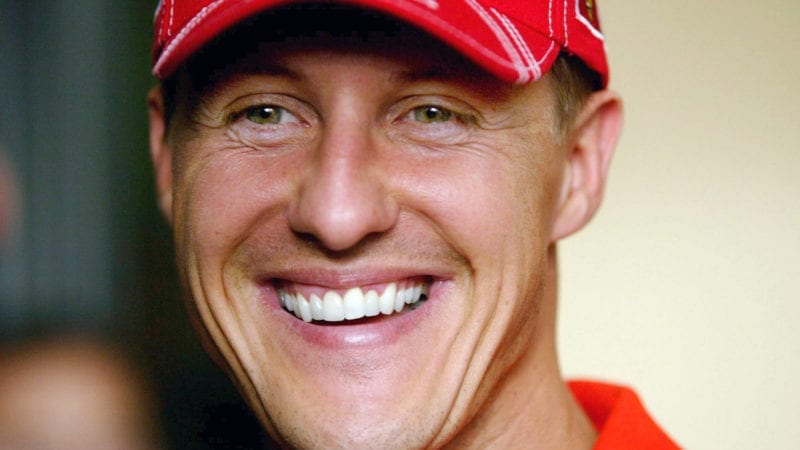

Hero, villain or nice guy? As the F1 giant is deposed in the record books by Lewis Hamilton, Mark Hughes assembles an all-star cast to discuss Michael Schumacher’s machine-like technique and uncover the real person behind the mask

Getty Images

Michael Schumacher is a complex subject. But perhaps quite a simple man. The F1 colossus who broke all the records that are only now being challenged by Lewis Hamilton was a perplexing fusion of supreme talent and insecurity, of great integrity and occasional on-track thuggery. Of humility and apparent arrogance.

Anyone who knew him well tells of a simple, good-hearted soul. It was visible sometimes when the guard came down for a few seconds; the smiling, fun-loving, normal man. “What do you think you would have been”, I asked him once, “if you’d not made it in racing?” “A mechanic, probably,” he replied immediately, “and very happy to be one.” A family man rather than a hellraiser, a blue-collar worker rather than an aspiring world leader (which is something that’s quite easy to imagine of a post-F1 Ayrton Senna, for example).

The challenges of such a man in dealing with the consequences of his immense talent – and possibly with the psychological effects of the circumstances around his childhood racing exploits – made for an extreme racing persona, the one associated with the questionable on-track moves. There was something within that persona that defined the result, the outcome, as everything: success or failure. Regardless – if it came to it – of how it was achieved. The will to prevail was extreme, skewed even, in a similar way to Senna’s before him. These are complex personas in an extreme environment, such that we really need the equivalent of 3D glasses to capture them in their full complexity. It’s that complexity which, in an era of racing where the car could be used as a weapon of intimidation, took them to territory out of reach to the mortals around them. But it comes at a cost.

“Sometimes you go down a certain path,” Schumacher said to Mark Webber in the wake of the infamous ‘parking’ incident in Monaco qualifying 2006, “and you cannot go back.” It was a rare but revealing glimpse behind the mask. There was no bravado about it, rather a vulnerability, a recognition of the very different animal that was created right out at the furthest edges of competitive intensity, to the very normal, nice, somewhat shy guy that he really was.

The will to win at all costs, an ability to drive on the edge and psychological shenanigans were a devastating mix, but Schumacher was always popular with his teams

That mask was usually all the outside world ever saw and it was hugely intimidating to his rivals when combined with the phenomenal level of ability. He projected that and clearly spent time and effort doing so. There could be no weakness in the facade. So as well as being vastly talented, he ensured he was fitter than anyone else and visibly so. He made sure he always had the best people around him, played up how good his car was rather than downplayed it, so adding to the impression of invincibility. But it took some psychological support to keep him there. He needed that racing family around him, an extended one that reached right down from Ross Brawn to the mechanics. But engendering that came naturally to him. Because he was a simple soul at heart and not a born superstar.

Those conflicting factors make for one hell of a cauldron to keep a lid on.

The Good

“I was driving the West Surrey Racing F3 car at Macau the first time I saw him drive,” recalls Eddie Irvine of his 1990 moment of revelation. “I was following this Reynard, which was an awful car that year, and I just couldn’t believe it, it was incredible what he was doing. He qualified it on the front row. I came in and said to Dick Bennetts, ‘I don’t know who’s driving that, but he is unbelievable.’”

“I think he was just better than anyone else I’ve ever seen,” says Sebastian Vettel. “He had a natural talent that is difficult to explain. I saw him karting and I joined him in the Race of Champions and got to see it close up. You see a bit more of the skill and car control. I think both those experiences showed me he had a natural ability I haven’t seen in anyone so far. He had an incredible work ethic and the combination of the two made him stand out. I haven’t seen anyone to match him yet.”

There are so many moments of extreme virtuosity in his F1 career to consider. Highlights include finishing second in Spain in 1994, while stuck in fifth gear for most of the race. Two years later at the same venue in the rain, where he was lapping sometimes three seconds faster than the others in taking the unloved Ferrari F310 to victory. The sequence of 19 ‘qualifying laps’ as requested by Ross Brawn that catapulted him past the McLarens for an unlikely win, Hungary ’98. So many more, all the way up to that last incredible victory, China ’06, in the last season of his ‘first’ F1 career where he came from a long way back in mixed conditions to beat title rival Fernando Alonso.

Driving for Ferrari, Schumacher’s 91st and final F1 victory was here at the 2006 Chinese Grand Prix. His next podium finish came in 2012

“He could make any old rubbish go fast,” says James Allison, who worked with him at both Benetton and Ferrari as an increasingly senior aerodynamicist. “It really didn’t matter if the car was ill-balanced or a bit of a pig, he would find a way to drive it round a lap and get pace out of it. He was much fitter than the people he was driving against in an era of refuelling-type racing where it’s just sprinty grands prix where every lap is not that dissimilar to a qualifying lap.”

“Michael carried all the speed in, never on the throttle until he was at the apex,” says Irvine. “I’d always pondered if that might be the best way to drive and with Michael, it confirmed it for me. You can get 95 per cent much more consistently by being point and squirt. You brake in a straight line, you get on the power a little bit earlier and you get all that speed down the straights. In the physics of the situation it’s not right but it kind of works because the straights are generally longer than the corners. Then I watched Michael and it was obvious his was the right way, even though I’d never done it. Then I started driving the way he did it and it worked for me in a lot of places, Monaco, Nürburgring, places like that.

But then when I came to the Monzas, I really should have gone back to my old way of driving, like Pedro [de la Rosa] or Rubens [Barrichello], who was a very point-and-squirt driver. With Rubens, there was no throttle trace, it was an on-off switch. That’s why at certain circuits he was very, very strong, but at Monaco, Hungary, places like that, he was really bad. After four laps I was quicker than him in Hungary [at Jordan] and he’d been running all day. Michael technically drove exactly how I thought you should drive. Even if you looked at him in the high-speed corners, he was just balancing the car on the throttle, even on the very high- speed corners, which is just insane. If you can have that feel. He was always working the throttle, apex to exit.”

In 1995, while the Britpop feud between Oasis and Blur fuelled the headlines, so Schumacher and Damon Hill squared up. Schumacher’s nine wins to Hill’s four gave the German his second world title

Faster in, faster out, Schumacher defied the conventions. He’d have the car on the absolute knife edge as soon as he turned in, just waiting to fly off the road if he made one more input. He had an exquisite way of optimising the weight distribution around the four tyres, often overlapping the braking and cornering phase, turning in early from a shallow angle, manipulating the dynamics to make it faster than the geometric ideal, using the brakes to have the car rotated early into the corner, with not much steering lock and the tyres ready to accept greater loadings.

That renowned analyst of car and driving dynamics Mark Donohue once said that being on the limit from apex to exit was like walking a tightrope. But getting onto the limit, the true limit, on corner entry was like jumping onto the tightrope from the ground – much more difficult. This is where Schumacher was unbelievably good, where his core skill lay. He’d do it like this from the first lap of the weekend, too. I recall watching the beginning of the first practice session at Pouhon in Spa, seventh gear, downhill sweep, one of the most testing corners for any driver back then. Everyone was playing themselves in and then this red thing appeared at a completely different rate to everything else, like it was on a qualifying lap. He turned in, the car visibly on the edge and he made not one single further input, just sat it there on that knife edge until he’d made the apex. The car needed just a sniff of extra loading and it would have flown off the road. You’d see these things regularly watching Michael trackside.

Eddie Irvine was Schuey’s team-mate at Ferrari from 1996-99

“He would do 76 laps looking like an accident about to happen,” says Irvine. “It was insane how he could do that. You give him an unbalanced car and he could just find a way around it; it didn’t really matter. That 1996 Ferrari was possibly one of the most pitch-sensitive cars of all time. It was horrible. But he just had the feel to adjust himself around it. That’s why he ran out of brakes in Imola that year because he had wound them so far to the front to try to stop the thing spinning. It destroyed its rear tyres because it was so pitch sensitive. To drive it like that took unbelievable ability.”

Willem Toet was an aerodynamicist at Benetton and has described what he found. “He told us he would push the accelerator to come out of the corner and the car would start to slide, so he’d come off the gas again, but this was happening faster than we could believe and, at the time, I think we were only logging the throttle position about 10 times per second. When we started logging the throttle position at higher frequencies, we could see that it was what he was doing. He was pushing the car into a slide, the yaw rate would begin to increase, then he would back off the throttle and the yaw rate would begin to decrease until he would get back on the throttle again. Something we hadn’t seen at that speed before from other drivers.”

It wasn’t speed of reaction – his reactions were consistently average when tested, “about the same as mine”, according to Ross Brawn. This was about an incredibly sensitive innate feel, a magical mix of neurons that determines why one driver is faster than another.

When you add to such ability an extreme work ethic, how was anyone else ever going to prevail? “He was incredibly into the detail and wanting to pour over the day’s work with his engineers and unhappy if he wasn’t spending every hour God sent on the test track,” says Allison. “He’d routinely finish each year head and shoulders above everyone else in terms of kilometres spent testing and that wasn’t when he was hungry for his first championship. That would be after his third, fourth and fifth championships. He was still out there just wanting to pound round Fiorano and Mugello, or anywhere else.”

“Actually I don’t think he was that great at sorting a car,” says Irvine, “because it didn’t really matter how it was, he’d still be fast. But he was very good with the engine, at feeling the engine because he was always working the throttle. When I went to Jaguar with the Cosworth, they’d been developing it with Rubens and so there was no half- throttle. We had to work a lot to sort that. Michael was better than I was with the engine. But the car, not really. He was so good it really didn’t matter.” That engine affinity, sorting out its response throughout its power curve and throttle movement was an absolutely intrinsic part in making Schumacher’s driving style work, as working the throttle against the grip from the apex on was how he made up for not having got on the throttle earlier, when his entry speed had made it unfeasible.

Monaco 2006: Schumacher was relegated to the back of the grid but still managed fifth

In terms of chassis balance there were still a few basics he sought, and in the three-year comeback with Mercedes he had cars which never quite gave him that feeling. I asked him about it at the end of that final season. “People say I like oversteer,” he replied. “I don’t. I can handle it and drive it but I don’t want it. With a neutral car you can have it sliding from turn-in to exit and all the time you can just drive on the limit of the four tyres’ given grip, and that’s what I’m always looking to achieve. I had cars that did that. With a little input you could make it go the way you wanted it to go. I haven’t had that since I came back.”

Jock Clear worked with Schumacher in those Mercedes years, having long worked against him when at Williams. He made an interesting observation about Schumacher’s process of developing the car. “I learned so much about how he was successful,” he said. “It is absolutely not about looking at the overlay and looking where you get on the power or the set-up sheet and choosing the right rollbar. It’s how he interacts with people that is the important bit, when he chooses to be tough with people and when not to be… He realised long ago that all the time these other guys were agonising about a rollbar. Just choose a rollbar and park that – now deal with some other things like bigging up the right people and getting them on side, looking to find an advantage that would play out longer term.”

“The thing I found that certainly drew him to me,” says Allison, “and I think anyone who had the privilege of working with him would say the same, was that he was very generous towards the people in the team, making them feel part of his championships, part of his successes. He made it feel to us like it was a team success and our part in it was real and he was grateful for it. That really does have the effect of galvanising a group of people to give their very best for you. Which is part of success in Formula 1.”

It’s also about how he was when things went badly. Allison recalls a particular instance in which Schumacher saw the bigger picture despite a miscalculation from his team that was literally painful. “Before the glory years arrived in ’98/’99 at Ferrari, there were plenty of mistakes made by the team and Michael would pay for those mistakes with not having equipment that merited his talent or with us screwing up, yet he never breathed a word of complaint. I can remember in particular feeling very guilty at a test at Monza where we’d pushed the undertray shape too far and the floor was prone to stalling. The floor had stalled through Curva Grande and he’d had a terrific shunt where the run-off at that time was perilous and it was mere chance he got away with it. He was horrifically bruised all down his buttocks and back such that he couldn’t sit down in debriefs in the races that followed. But he never breathed a word of complaint, just got on with it. Didn’t say anything to the outside world, just raised an eyebrow at me and the aero team and said, ‘Can you sort that out please?’ Those things make you feel very warm towards a person because it’s not just one incident, it’s continuously acting properly as a team mate, and you’d struggle to find anyone who worked with him who would say different.”

The Bad & The Ugly

High jinks at Jerez in 1997 with Villeneuve – there was widespread condemnation

There was a linearity in Michael’s attitudes, a certain ‘with me or against me’ that affected his general relationship with the media. That linearity was seen too on track. He’d programmed himself to win and hence anything else was subservient to that. So there were the patented start-line chops which ironically came from his literal reading of the ‘one-move’ rule that had been brought in largely because of him. There were the now-infamous incidents of title-deciding consequence at Adelaide ’94 (with Damon Hill) and Jerez ’97 (with Jacques Villeneuve) – and of likely grand prix victory-denying consequence with the Monaco ’06 ‘parking’ incident in qualifying.

Unlike the ostensibly similar incidents of Ayrton Senna before him, these Schumacher fouls didn’t carry obvious premeditated cynical intent. They were more like competitive panic. As if in the millisecond of realisation of his potential failure to achieve the task, he couldn’t allow it to happen and all reason was short-circuited.

“I loved the guy in every respect,” says Pat Symonds, his engineer at Benetton. “In my mind he was one of the nicest guys I ever worked with. But he wasn’t flawless. Some of those incidents he’s infamous for are a reflection of his incredibly competitive nature and the fact that his first reaction is competitive before ethical. But none of them were premeditated. I honestly think he would never do anything premeditated and I suspect afterwards he was always full of remorse. But I’d never criticise him.”

“Michael by his own admission made some questionable moves on the track,” said Ross Brawn to Motor Sport in 2014. “At Jerez when he hit Villeneuve, he came back to the pits and said, ‘That bastard ran into me, that bastard had me off,’ and I said, ‘Michael, stop. You need to look at what went on.’ And when he did, he said, ‘Oh s**t, that was me, wasn’t it?’ At that level of commitment to win, it’s right on the edge. That’s what makes Michael so special. He’d been through those situations and although I didn’t like it, I stood by him in support. Similarly at Benetton, there were things which I did and which the team did that he didn’t like but stood by and supported regardless.”

No smiles from Damon Hill at the Adelaide press conference in 1994 following a collision which handed Schumacher the world title

“He genuinely believed he was always right,” says David Coulthard. “After our coming together at Spa [in ’98] and our big argument, after it had all died down, we talked and I said, ‘Michael, can you not accept the possibility that sometimes you may be wrong about something? Can you honestly tell me you’ve never been wrong?’ And he thought about it for a moment and then said, ‘No, I’ve never been wrong’. If he really believed that – and I’m still not sure if he wasn’t just winding me up – it would be an incredible strength in competition.”

Prevailing through his strength – and projecting that strength – was very much at the heart of Schumacher’s approach. But according to Clear, that came from a place you might not expect. “If I compare with Lewis,” he said back in 2015, “Lewis’ centre of gravity is that he 100 per cent knows he is the fastest. If the times don’t reflect that, then there’s something wrong. But with Michael there was an insecurity that he might not be the fastest and therefore he had to do absolutely everything in his power to ensure anyone who might be faster couldn’t beat him.” That included both the work ethic and how he projected that front of invincibility

Parked on a double yellow at Monaco 2006

“Michael was a psychological warrior,” according to Mercedes team-mate Nico Rosberg. “It was incredible learning for me over those three years. And he didn’t even have to make an effort – it comes naturally to him, to try and psychologically get into the head of his competition. And it would be from the morning to the evening. He’d love to walk around in the engineering room topless just to show his six-pack. Just another statement of strength. It just went on and on. Infinite examples like that.

“When Michael came along he was like God in the team. We had some strategy meetings and even my strategy was being discussed with Michael and not with me! Even though I was sitting there! I’m sure every day after getting up, he would think, ‘How do I make my team-mate small?’ Lewis was actually more natural, it came easier to him. But Michael was just the complete package, though he was a little bit beyond his peak by then. He had very strong peak performances, even did pole position in Monaco in 2012, his last year. But the consistency wasn’t there.”

“He definitely got involved in too much on track,” assesses Irvine. “Look at Hamilton. Lewis is a much better racer. He’s so clean, it’s incredible. He overtakes people and very seldom gets involved and even when he does I kind of believe he wasn’t so much to blame. Look at Lewis’ track record for that, then look at Michael’s. But Michael carried some donkeys around the track. He was on the limit with the car already and then you add to that he has to deal with an overtaking manoeuvre, so you can’t really properly compare. I could maybe justify that to an extent. But definitely too many incidents. Michael was all about the level of his driving rather than his racing.”

In his 2015 autobiography Aussie Grit, Webber reflected on what Schumacher had said in that post-Monaco ’06 chat. “He told me straight and just showed me what he was prepared to do in order to win. I was happy he had the respect for me to tell the truth. Michael was an absolute phenomenon, but the levels he would go to just to keep being successful… That’s the way he was wired, he was such a ferocious competitor, always on the edge. Would you be comfortable looking in the mirror and saying, ‘This is what I did to achieve success?’”

The Balance

When looking back at the story of how Schumacher, a kid from suburban Germany whose father was a bricklayer, came to be racing at all, there may be vital clues to many of his subsequent attitudes. That win-at-all-costs mentality may have been more than just competitive make-up, as much nurture as nature. His family had gone into debt to get him to a basic level of karting. When others, seeing his obvious potential, began to help financially, he pretty much enlisted himself to them. The fanatical work ethic became apparent at this time, as did the absolute requirement, perceived or real, to win.

Michael grew up quickly away from his family on the karting circuit;

From 11 years old he was basically on the road at weekends, away from the family, feeling he absolutely owed these people. Over time there were several of these benefactors, a couple of them only with his interests at heart and absolutely critical to his ultimate success, but others he described as “often difficult people. They lacked respect for my friends and my family and were often underhand or unfair and not always straight.” Not always kind when he didn’t win, either.

For this simple kid away from home, feeling a huge responsibility upon his shoulders, it’s easy to see where a fairly simplistic linear attitude to winning may have taken hold. Later, when he won some prize money, he used it to buy his parents a car and pay the insurance.

But his parents weren’t with him as he did his stuff on the karting tracks of Germany. They couldn’t afford it. “It wasn’t an easy life for my parents,” he’d later recall. “Most of the time I was away with people who had nothing to do with my family. From the age of 11. Was I already a little adult at 11? Yes, I had to get used to living with all kinds of people, had to deal with various characters.”

This was a very different situation to that of a young Ayrton Senna, son of a wealthy man, or even of Lewis Hamilton, backed to the hilt by a loving family and a proactive dad. This was a more brutal formative experience.

This is where those 3D spectacles are needed to see the cumulative effect of nature and nurture on the traits of these pre-eminent greats. While Schumacher certainly wasn’t shy of going wheel-to-wheel, there’s a sense that he would rather avoid the on-track challenge by his preparation and work behind the scenes. The result overrode all.

Hamilton seems to relish the jousting, ‘the dance’, as he sometimes refers to it, the sheer love of the game in the moment. With Senna, absolutely used to having his world aligned the way he wanted it, it was almost as if he took any wheel-to-wheel challenge as an affront, anything which disguised his level as an outrage. That’s three very different perspectives from the top competitors of the last three generations.

Allies Jean Todt and Ross Brawn at Ferrari – the ‘three legged stool’

Formula 1 tends to bring exceptional individuals together and that certainly applied to Schumacher’s career, which must always be seen in the context of Ross Brawn and Jean Todt. The relationship with Brawn was built at Benetton. “We grew up together at Benetton,” recalled Brawn. “My formative years as a technical director were Michael’s formative years as an F1 driver and we both made mistakes, were both wet behind the ears. That really made our relationship very special; we went through all that controversy together and stood by each other. It was a bit traumatic at times. It was like we’d been in the trenches together. We came out the other side after a lot of pain and aggro.”

That relationship deepened at Ferrari where they and Todt formed a protective forcefield, which the destructive elements of that team could not break through. “Ross, Todt and Michael were a three-legged stool,” says Irvine. “If one of them went, the whole thing fell over. And they knew that. Michael protected Todt. Todt protected Ross and the technical team from the Ferrari politics and Michael was by far the best driver in the world. So that’s how it worked. I hear it said how he had subservient team-mates and it was impossible to compete, but actually that’s nonsense. If you were quicker you’d have got the treatment. But no-one was ever quicker. In the time I’ve known Formula 1 there has never been anyone so much better than the others racing against him. People talk about Mika [Häkkinen]. I love Mika, he’s an amazing driver, but not in the same league. No-one was.”

Given the opportunity of F1, he was a great enough driver to have succeeded even without the ruthless moments for which he became infamous. But his only possible route to those opportunities was a painful one and probably left its mark upon him. The sheer physicality of Schumacher’s racing – and who can forget how close he had Rubens Barrichello up against the pitlane wall at Hungary in 2012 – and that of Senna, was only possible since racing became safe enough to use the threat of contact as a weapon. For a brief time, this mentality seemed to be required to differentiate. Back in the ’60s and before, everyone was aware of how lethal it was, and all you needed then was talent. Hence the impeccability of the records of Fangio, Clark, Stewart, etc.

Hugs for Schuey from Ecclestone at the 2000 Hungarian GP. David Coulthard, Mika Häkkinen – who won in some style – and Rubens Barrichello complete the line-up

But Lewis Hamilton is interesting because he doesn’t ever cross that line which Senna and Schumacher used to do whenever it was necessary. He goes right up to within a millimetre of it but doesn’t cross it. So just as Senna and Schumacher could be seen as evolutions of the genus to accompany the changes in the sport itself, so Hamilton can be seen in this light, too – but evolved further from Senna and Schumacher. Today you could not now prevail by repeatedly crossing that line because the sporting regulations now carry severe penalties for doing so. To be at the top, Senna and Schumacher would both now have to race in a very different way to how they did.

So let’s appreciate Michael Schumacher for the giant of a racing driver he was and recall him as the very warm human being behind the mask. The controversies shouldn’t define him. He was a true great.

|

Official Motor Sport Magazine Calendar | 75 Years of F1 | 2025

• A stunning image of Michael Schumacher taking on Monaco in his 2003 Ferrari 2003-GA features as part of Motor Sport’s 2025 calendar, celebrating 75 years of the Formula 1 World Championship Click below for full details: |