Formula One 2000

By Gordon Murray It all came from a comment Gordon Murray made over five years ago. We were talking about the then just launched McLaren road car he had designed…

There’s a distant whine of electronics, followed by a whip crack of starter motor… then all hell breaks loose. The source of the noise is out of sight, but it’s almost ungodly as it echoes around our largely lifeless surroundings, the empty buildings and grandstands of Rockingham capturing each glorious decibel and reflecting it back into the pits at the centre of the bowl.

It sounds like the biggest, angriest swarm of hornets that nature could muster, each armed with a chainsaw for added effect. There’s a flash of yellow and red as it rounds the final chicane, and then the tempo rises to the point of deafening crescendo when you’re finally forced to admit that leaving your earplugs at home was actually a bad idea.

This is the sound of a V12. And not just any V12. Perhaps one of the most important V12s ever to come out of Maranello, and it’s certainly bringing this place back to life.

While Rockingham closed its doors for licensed racing at the end of last year, it’s still available for now for private hire and the track is largely as it was – barring the lorry park that’s formed around the back of the oval layout. It’s quite a contrast – grey disused race circuit meets stunning race car that’s as shouty to hear as it is to behold.

“It’s 120 decibels on the throttle, and is just as loud inside as it is outside,” says the car’s owner Mike Humphreys, a keen racer in both modern and historic machinery. “I just love it. It was one of those spur of the moment decisions to buy it, I went looking for a modern GT car and just couldn’t resist it! It’s fast, loud, beautiful, and has a 6-litre V12… there’s not much to not love about it.”

The 550 Maranello GT1 was a game-changer for Ferrari, even if it never really got the plaudits it deserved during its relatively short competition lifecycle. Ferrari had been absent from top-line GT racing for the best part of a decade until this car arrived. And not just this model. This actual car.

This is 550 Maranello chassis F133GT 2102 – the first factory-produced competition 550. It was this car that almost single-handedly brought the Prancing Horse back into sports car racing at a key period.

I’d almost forgotten that GT cars sounded like this amongst the modern era of smaller capacity forced-induction powerplants that dominate the current GT racing landscape. But back at the turn of the millennium, this was the unrestricted, unrelenting soundtrack to the world’s best sports cars. There was something gloriously raw about the early 2000s GT1 era, and the 550 Maranello typifies many of the things that made it great.

It’s actually a product of the privateer innovators, rather than the factory boardrooms, meaning it was built with performance and passion in mind, rather than marketing. The sport was changing fast at the start of this century and, while Michael Schumacher had just embarked on half a decade of dominance for Ferrari in grand prix racing, the firm was missing a trick elsewhere.

Following the F40 LM programme of the late 1980s, Ferrari switched focus to pumping out single-make Challenge cars in the middle of the 1990s after withdrawing from FIA-sanctioned competition following a rules row against its old nemesis, Porsche.

At the time GT racing was undergoing a renaissance. After production racing was largely killed off by the shift toward prototypes in the early 1980s, and then the collapse of the World Sportscar Championship in 1992, there wasn’t much GT racing of note until Stéphane Ratel, Jürgen Barth and Patrick Peter formed the BPR Global GT Series in 1994, which promptly gained so much traction it morphed into the FIA GT Championship for 1997. Manufacturers finally had a new stage to show off their designs against the competition, and Ferrari’s F40 was a building block of that environment.

However, that design was rapidly becoming outdated against the likes of the McLaren F1 GTR, so Ferrari set about developing its successor – the F50 GT. Three cars were built, and extensively tested, but things fell flat when Porsche unveiled its 911 GT1 in 1996. GT1 was conceived as a place where manufacturers could modify their current road cars to go racing. But Porsche did things the other way, building the GT1 as a pure-bred racing prototype, and then creating enough watered-down road-going versions to satisfy the rules. Ferrari’s toys swiftly exited the pram, and so did the brand from top-flight GT racing. The F50 GT was never raced, while Porsche kick-started a development war with other rivals.

That was that for Ferrari until two years later when it began to receive extra orders for its road-going 550 model, which had been designed, developed and produced without even the slightest intention of taking it racing. First introduced in 1996, the 550 took Ferrari very much back to its heartland design – a nimble chassis mated to a front-mounted 5.5-litre V12 and wrapped in aerodynamic Pininfarina bodywork.

It didn’t take long for privateer tuners to cotton on to the design’s performance potential. The first competition version came about in 1999, when noted rally car builder Michel Enjolras struck a deal with the Italtecnica fabrication and tuning firm to build a racing variant. That car, run by the Red Racing team, competed in the French GT Championship in 1999. But things began to snowball when former rally driver Frédéric Dor commissioned British firm Prodrive to build a series of 550s to FIA specifications, and with a specific focus on the Le Mans 24 Hours. Dor founded Care Racing Development to look after the cars, and donated his own road-going 550 to be the first of the batch.

Prodrive essentially cut the car to pieces and started from scratch, with a steel monocoque chassis harbouring all of the vital components – including that hulking V12, which had now been expanded to six litres. Over four years, 10 550s were built by Prodrive, and were successful from the start, winning races in the FIA GT Championship in 2001 and 2002, plus the odd victory in America, and then eventually winning the GTS Class of the Le Mans 24 Hours in 2003.

Meanwhile, Italtecnica built more cars, as did German privateer Franz Wieth. Suddenly the 550 was a regular sight in GT series across the world, and Ferrari wasn’t actually directly involved with any of it.

With all this success happening with Ferrari’s product but not its own expertise, something had to change. So the factory contracted N.Technology to build a ‘proper’ 550, with official components, in Ferrari’s name.

N.Technology already had an ‘in’ with Ferrari, given it was running Alfa Romeo’s factory touring car programmes, and had been responsible for all of Fiat’s racing activities since its formation. With Italtecnica looking after the development of the near-600bhp V12, N.Technology produced three chassis, which were all given official Ferrari competition chassis numbers. One became a show car and never raced, but the other two were prepared by Ferrari and placed with JMB Racing for FIA GT in 2003. Ferrari used the cars as rolling laboratories for development of the forthcoming 575 GTC model, which would be its first true customer GT car since the F40.

This, as one of those two, is then a properly significant car. Arguably the model that made Ferrari fall in love with GT racing again. And N.Technology used some trick engineering solutions to help it succeed.

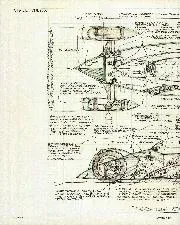

The V12 was moved further back toward the driver and fitted low in the chassis with custom engine mounts. To even out its weight, certain elements were moved to the rear, with the single-piece sequential gearbox and differential mounted in the boot, as is the battery, power steering pump, alternator and dry sump system. With the engine almost behind the front axle, and the gearbox and ancillaries just in front of the rear one, the majority of the weight sits in the centre with the driver, avoiding much of the nose-heavy handling constraints of other front-engined cars of the time.

“It’s beautifully old school, but has some really trick pieces of kit for the time,” says Kevin Clarke, who now looks after the car for Humphreys through his Intersport Racing concern. “It doesn’t have all of the electronic gizmos modern GT cars do, but it has a particularly good differential, so whenever it slides it’s always controllable. You can light up the tyres at pretty much any speed if you want to, but the car is very well balanced so you can always catch it. To get the best from it you have to keep it on the limit, which is right inside the sideways mark. You have to rely on the huge power and torque to do the work, which makes it a brilliant drivers’ car.”

Clothed in lightweight carbon fibre bodywork, this car was campaigned by Philipp Peter, Fabio Babini (and Boris Derichebourg for the longer-distance races), most notably in that year’s Spa 24 Hours where it led the Prodrive-built BMS Scuderia Italia entries before engine issues.

With the 575 incoming, the two factory 550s were removed from competition and mothballed into storage at the end of 2003. With the 575 being the last racing Ferrari to use a V12, the 550 was the car in which the final spec of this special engine was developed.

“The hillclimb victory earned a letter from Jean Todt himself”

That could have been the end of the story for the factory 550s, but chassis 2102 was rescued by amateur racer Piero Nappi in 2005, and used to win multiple rounds of the Italian Hillclimb Championship. Nappi’s title success would be a rare hillclimb win for Ferrari in the modern age, and earned Nappi a personal congratulation from then-Ferrari president Jean Todt, who proclaimed Nappi to be “an essential element to defending the prestigious name of Ferrari”. It also proved that the factory was still keeping an eye on this particular 550.

Nappi sold the car two years ago to Humphreys, who had an interesting first experience of the 600bhp V12. “We went to Naples to see the car, and I test drove it around a local go-kart track, which wasn’t an ideal introduction considering the car was as wide as the track and the main straight was about 100 metres long. I basically checked first and second gear worked and put my money down!” he says.

“Piero had tried to auction the car a few times before, mostly locally, and once he even put it into a furniture auction in Padova, so no wonder it didn’t sell. I saw a small advert for it online, and it just looked like a tatty hillclimb car, but there was a tiny picture of the FIA papers and Ferrari letter, and I could just make out Jean Todt’s signature. That’s what sold me.

“The car’s unbelievable to drive. At eight tenths it’s a pussycat, albeit a loud one. It had just had an engine rebuild when I got it, but we took the gearbox apart to check that and five dogs just fell out of it, so we had that entirely redone.

“It’s got good grip, but just phenomenal grunt – it’ll spin its wheels right up the rev range in first, second and third if you let it.”

Humphreys has restored it to its Spa 24 Hours livery and has used the car in demonstrations at the Le Mans Classic, and plans to give it a full racing return in the coming seasons. “I plan to start racing it, as I’ve only driven it for demo events at Le Mans and Paul Ricard with the Global Endurance Legends, but I need a fair few test days first,” he adds. “There’s a lot to get used to, as the car actually creates a decent amount of downforce, so it’s adapting to the difference in cornering speeds with the aero and the big slicks and brakes.”

With plans to race once again after a 16-year lay off, it can only be good news that a fair few more circuits could soon be filled with this same sweet sound, very soon.