How Ken Miles helped Ford beat Ferrari at Le Mans '66

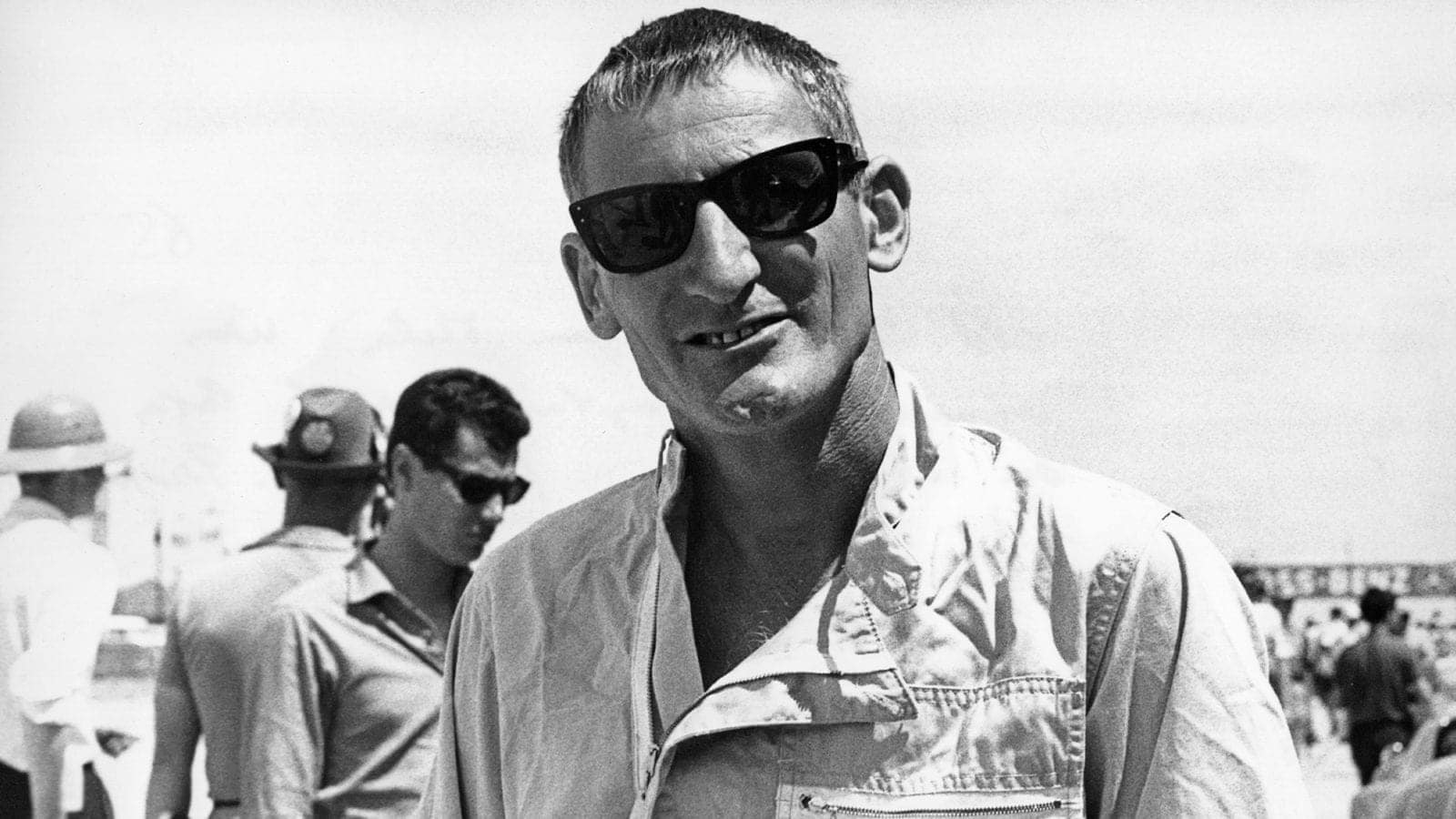

Ken Miles, the unlikely man behind Ford's Le Mans triumph

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

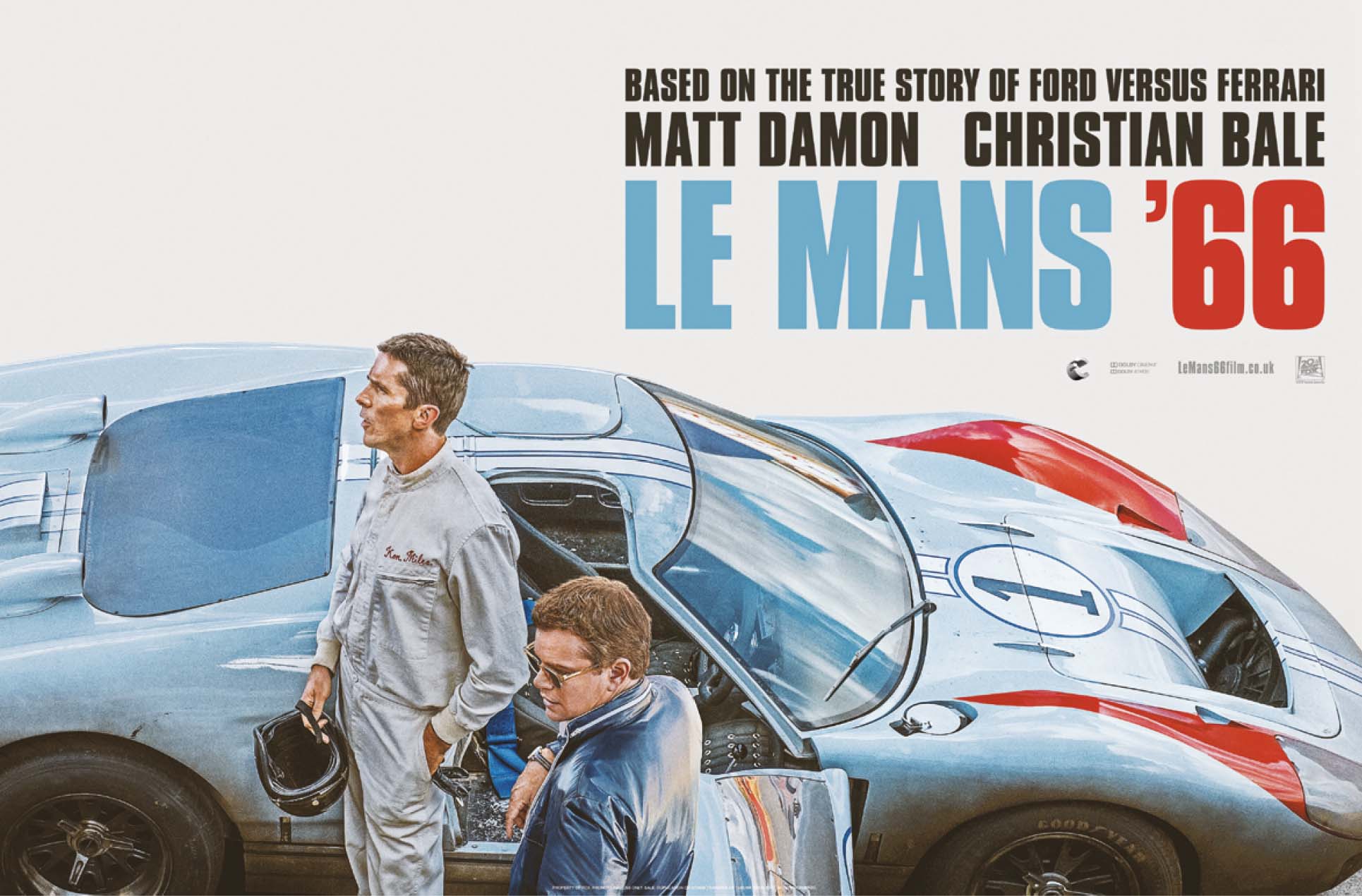

That muddled triumph of 1966, when three Ford MkIIs bellowed across the line at La Sarthe to claim victory for the Blue Oval without knowing who was first, forms the dramatic core of the new fact-based film Le Mans ’66 (or Ford v Ferrari in the US), and surprisingly it picks out a relatively unknown English driver and engineer to head the US cavalry against the bad guys – in this case that foreign fiend Enzo Ferrari.

So does a rangy, laconic bloke from Sutton Coldfield deserve a film built round him? Is he the key to Cobra and Ford MkII success? He certainly won a bundle of races right from the start, in cars he modified himself to go absurdly fast. That’s a good mix – rapid driver, inventive engineer, intuitive tester. And if you throw in your lot with a powerful Texan who can assemble the might of the Ford Motor Company behind him to tackle the biggest prize in European racing, then you have the makings of a pretty good story. And that’s real life, before Hollywood gets its hands on it.

Far from the film lights, and California, Ken Miles displayed mechanical talent through his 1930s Midlands childhood playing with bikes and cars and visiting Donington Park. He’d built an Austin 7 special by the age of 15, abandoned school to join Wolseley a year later (his wife Mollie later wrote that “as a scholar he was a dead loss”), joined up within days of war being declared in 1939, and became a staff-sergeant in REME, the army’s engineering arm. There he developed a respect for American machinery, and in 1943 wrote to Motor Sport about its “great promise” and suggesting he would build a “supercharged 4WD trials job of my own design”.

Standard issue was never going to be enough for this ambitious man.

What he did do was drop a blown Mercury V8 into a Frazer Nash which went like stink on hillclimbs and circuits. Miles was marking his territory but the British motor industry, struggling back from war, wasn’t interested. A stint building 500cc F3 cars proved a financial failure, so when a Wolseley contact offered him a job in a Californian MG dealer he jumped, with wife and young son. December 1951 brought a permanent goodbye to a ration-stifled, inward-looking England.

And within four months at Gough Industries this beaky beanpole was racing and winning in a standard MG TD, while also building an MG special which won its first race in 1953. A year or so after, he produced The Flying Shingle, another MG hybrid which showed the dominant Simcas and Porsches the way home.

Photos show him usually wearing a tie, hair neatly parted, BRDC badge evident. He might be living under West Coast sunshine, but he doesn’t look American. There was a trace of Brum in his speech, and he talked from the side of his mouth – some Americans didn’t understand him. It wasn’t affectation, says his son Peter today: crashing a motorbike paralysed the facial nerves on one side. Nor did he modify his demeanour: first-hand memories quoted in Art Evans’ book on him use words like outspoken, aggressive, opinionated, sure of himself, maverick – as well as warm, fun, nice to be around, keen to help others. One day he’d be your best mate; the next he’d walk right past you. There’s another message too: Miles drove his cars “right out to the edge”; second would never be good enough. The impression is of a man who saw his path and was not to be deflected; a good friend if you weren’t trying to direct him. No surprise that in 1955 an argument precipitated his departure from Gough.

He’d been noticed, though. Racer Tony Parravano loaned him his Maseratis and Ferraris that year, and as “the number one 1500cc pilot” he began to drive Porsches extremely quickly for marque importer John von Neumann.

Despite that early departure from school Miles proved a literate writer, contributing many articles to racing titles including Road&Track, about wearing helmets (he always did) or trying to persuade the blazered West Coast crowd not to worry about pro drivers, a sticky point socially.

He also wrote praising the little guy – the shoestring privateer racing for pleasure, not glamour. Maybe it was such disruptive views that nettled people: he was soon embroiled in an unpleasant anti-Miles print campaign. Objecting to being made to take a rookie test, he resigned from the SCCA and was refused re-entry. As a three-time president of the California Sports Car Club and the man steamrollering the 1500cc classes this was an embarrassing spat that looks entirely personal. In creating a competitive sports car race programme Miles had upset the old boy world of Southern California racing.

Still, in 1956/57 those 550 Porsches were bringing in the silverware – 24 wins and 12 seconds; in between Miles decided a better mix was to drop a four-cam Porsche unit into a Bobtail Cooper, which was a winner until Porsche importer von Neumann got a message from Stuttgart saying stop it. More ingenuity, casting the ideas net wide.

Faster cars were now coming Ken’s way despite falling out with von Neumann – Otto Zipper’s RSK Porsches and Ferraris, even faster Porsches for wizard tuner Vasek Polak – and as Ken often contested the big-engined class he was mixing with up and comers like Phil Hill and Carroll Shelby. They noticed.

By now a naturalised American citizen, he had opened his own tuning and preparation shop in North Hollywood, where in 1961 a Londoner called Charlie Agapiou saw a sign saying ‘English mechanic wanted’. “I walked in and Ken took me on right away,” says Charlie today from his California Rolls-Royce showroom. “I didn’t know he raced, but soon we were going to meetings in his ’54 station wagon towing the Alpine. I loved it, and so did he, so much so it was bad for the business! Ken was both a great boss and an impressive driver.” That was confirmed by his winning the 1961 USRRC championship.

That Sunbeam Alpine was a flag-waver for the British maker, but noting Shelby’s experiments with a V8 in an AC, it asked Miles to fit a 260 Ford V8 in an Alpine. “We had six weeks to do it, and we did it,” says Charlie, London still clear in his accent. “He was fast, and I learned so much from him.”

Meanwhile Shelby, now retired from racing, asked Miles to test his Cobra-to-be and recognising a good development man made him an offer. “Ken closed the shop and I was out of a job!”, says Charlie (although in fact it was the tax authorities who made that decision…) “Then a few weeks later he invited me to join him at Shelby. I said I didn’t know enough, but he said ‘you bluffed me, you can bluff them’”.

Very soon Miles was competition manager as well as development driver for Shelby American, and thanks to his rigorous work and firm project management the unsophisticated 289 Cobras got faster, taking SCCA GT honours in 1963 and the USRRC constructor’s crown in ’64, all leading to the low-drag Daytona coupé which took the WSC GT title in 1965. But Miles was frustrated, says Agapiou. “He couldn’t just watch, he wanted to drive.”

By now the GT40 and Ford’s project to unseat Ferrari was under way. Books, and the film, love to depict this as a personal bullfight between capricious Enzo and a red-faced Henry Ford II, incensed at Ferrari rejecting his buyout offer. Leo Levine’s 1968 book The Dust and the Glory tells a different story: that the GT40 scheme was driven by Lee Iacocca, Ford’s vice-president. Unlike Henry II he believed racing sold cars and instigated the Total Performance programme that embraced Indy, NASCAR and drag racing plus saloons and rallies in Europe. But with nothing to contest the sports car arena Ford turned to – Slough, creating Ford Advanced Vehicles (FAV) combining Eric Broadley with John Wyer and US-based British engineer Roy Lunn, both of them involved in Shelby’s 1959 Le Mans victory with Aston Martin. It was a circle waiting to be closed.

“Ken deserved more credit for Ford’s success than anyone”

But long-distance corporate management doesn’t work in racing, as a dismal 1964 proved with seven DNFs, and deciding that the British end was not performing Ford split its efforts, handing two cars to Shelby American in Los Angeles while letting FAV go its own way. For Miles this was perfect – an experimental car he could steer to success, but he wanted to steer it in both senses, and his cowboy-hatted boss gave in. After two months’ frenzied development inserting a brawnier 427 motor and a ZF gearbox, Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby crossed the 1965 Daytona 200 finish line to score the car’s first triumph. It looked as though Shelby had worked his magic, and if it was that Limey who’d done the donkey work, who cared? Charlie is clear about this: “Ken deserved more credit for Ford’s success than anyone. He was brilliant.” He adds “Shelby used to come in and chat but he never bugged us in the shop”.

You might think two alpha males were set for trouble, but Shelby and Miles in fact had a good rapport. “We got along just fine,’ said Shelby in Evans’ book. “He was the heart and soul of our testing program. He took a pile of s**t, the Daytona coupé (and I hope you print that) and made it work. Every day Ken was out there testing, or he was in the shop cutting metal and bending things around. He made a racehorse out of a mule.”

Ken’s sensitivities as a test driver – he drove with fingertips and memorised behaviour like a human data-logger – along with the skills of legendary fabricator Phil Remington had turned a corner for the faltering GT40 project, but it was a false dawn. Apart from second at Sebring (Miles and Bruce McLaren), the rest of 1965 was embarrassing, culminating with six cars failing at Le Mans – Shelby’s 7-litre pair plus the smaller-engined quartet Wyer and FAV were determined to make work. ‘Total Performance’ had turned to ‘Total Embarrassment’. Miles had done better in 1955 when he came 12th in a works MGA.

“Ken was always out there testing, or in the shop working. He made a racehorse out of a mule”

Yet Shelby was set on hewing an American winner out of this fractured Anglo-American enterprise, and so was Miles. “He was determined to make it a winning team,” says Agapiou. “He wanted that car to work. He was committed to Shelby 100 per cent”.

As well as testing, Ken was also developing the GT350 Mustang and racing the Cobras. It was another of his strengths – sheer toughness. Stringy as he looked, and by now in his 40s, he exercised and ran every day, and didn’t smoke or drink much. Fellow driver John Morton recalled him driving a Cobra in a very hot 100-mile race at Watkins Glen, then doing another 180-miler in it without any signs of strain.

His son Peter Miles, later an off-road racer and now in charge of Chip Connor’s magnificent car collection, remembers those times. “He was away a lot, but he took me to Le Mans in 1965, and we went on the road in one of the GT40s to test at Willow Springs. And he let me drive a pre-production street car Cobra on the track – I was about 15. He was interested in science fiction and psychology and extremely focused – he would walk down the grid and stare out each driver to intimidate them before the start. He was really competitive.”

Yet rivals knew him as that proverbial tough but fair opponent who’d leave you space plus one inch, and not a complainer: he just shrugged his shoulders when once disqualified for grabbing a cup of water during an SCCA race while way ahead – constituting an illegal pit stop…

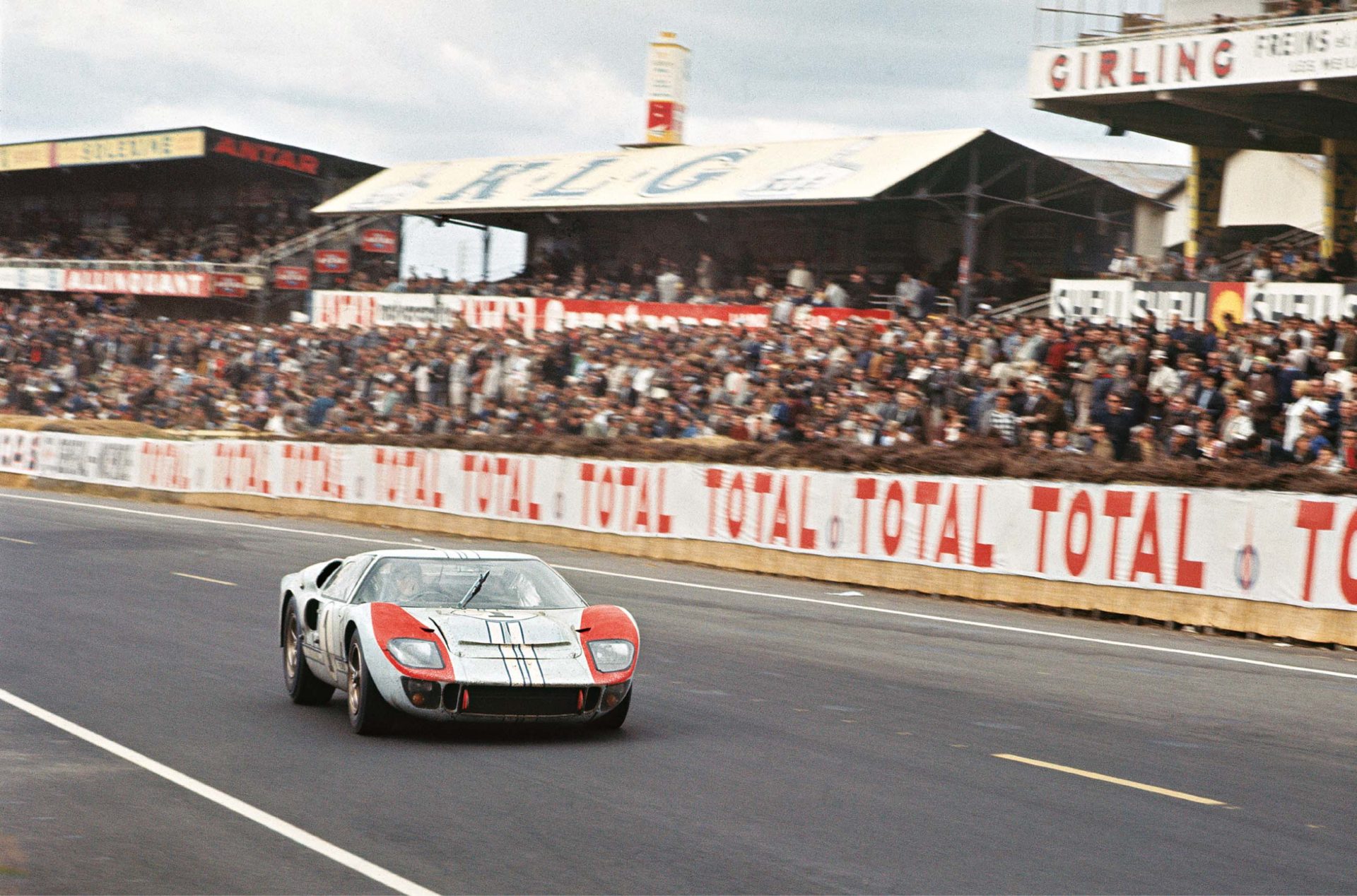

After two turbulent years, 1966 would finally justify the millions of Ford dollars, and Ken Miles was right in the centre. Arriving at Daytona with three 7-litre MkIIs, flanks bulging with air scoops, the team had talent to spare: Miles/Ruby, Dan Gurney/Jerry Grant and Bruce McLaren/Chris Amon. Yet it was Miles who set pole, and 24 hours later, Miles who headed a Ford 1-2-3. Sebring, next round of the World Championship, added another Ford triple with Miles ahead, this time against works Ferraris. The MkII was finally fit for Le Mans.

No-one had ever seen an operation like it: eight cars in three teams, a dozen spare engines, 21 tons of spares – and Henry Ford II himself languidly flagging off the race. There was no option – Ford was going to win and with the works Ferraris falling out in the latter stages it put three MkIIs ahead. Miles, though, could not stop racing his team, first Gurney/Jerry Grant until a gasket went, then Chris Amon and Bruce McLaren. Then Ford decided that three abreast would make a perfect PR coup and issued ‘close up’ orders.

“We began to see ‘slow down’ signals,” Amon told me in 2006, “but Ken kept going and Bruce was pretty pissed off about that.”

In the last minutes Miles did back off, letting McLaren close up, with a Holman Moody MKII following, but it was McLaren who crossed the line feet ahead.

“There was no way Bruce was going to finish second”, said Amon. “He said Ken backed off; well, maybe – or maybe it was that Bruce put on a little spurt…” Hulme too later said the New Zealander had put on a final sprint to the line.

Yet everyone assumed it was Miles and Hulme’s win. “We tried to push the car into the winner’s enclosure,” says Agapiou, “but they waved us away. Ken shook his head and walked away, but he came back in his duffel coat, congratulated the winners, posed for photos. But he was very upset. He was gipped out of it.”

Victory would have given Ken Miles a unique triple – Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans. Thankfully there was the new composite Ford J-car to develop to keep him occupied. Two months later it killed him.

“It was the last lap of the day, and I just saw a ball of fire. They kept me away, but I could see him…”

There’s no definitive explanation of what happened that August test day at Riverside; Peter Miles says two black lines suggest the rears locked. But Charlie Agapiou reckons a last-minute mod to the seat belts was crucial: “Ken was a skinny guy. We had to shorten the belt mount, but while we welded it, on the J-car they riveted it and when he hit the rivets snapped. He slid under the bulkhead and his helmet got caught.”

Peter Miles was there. “It was the last lap of the day, and he was pushing hard. Suddenly it went quiet and I saw a ball of fire. They kept me away but I could see him. It’s a bit traumatic seeing your father lying dead in the dirt.”

Miles died from massive head and internal injuries. The following Saturday the funeral chapel overflowed with mourners. Shortly after, says Peter, his mother disposed of all Ken’s trophies. “I’m still trying to collect some back…”

Now it’s big-screen time for the man from Sutton Coldfield. Charlie Agapiou was a consultant on the film. “Matt Damon was into the Shelby thing, but Christian Bale wanted to know everything – how did Ken walk, talk, his traits. He did a good job; he does seem like Ken. They weren’t allowed to do pitstops the right way – too dangerous. But they made a bloody palaver of Ken’s door! [Miles had to stop for a loose door] It took about 20sec, but they have three guys hammering at it.”

Peter Miles: “I gave Christian everything I had on Dad including voice recordings. He hired a linguist to try to pin down Dad’s accent, but I haven’t seen the result yet.”

However filleted and simplified the screen version, it doesn’t change Ken Miles’ legacy. Prickly, maybe, but talented, with the ability to find the limits that wring victory from a reluctant car, to feel what was going on underneath him and use that to extract yet more speed. “The best test driver I ever knew,” said Shelby.

“He put Shelby American on the map,” says Agapiou. “They were lucky to have him. I still miss him.”

Says Peter Miles of the father he lost trying to find that next tenth, “He was an extreme Type A-plus personality”. The sort of guy who makes a good movie hero.