“Jano said, ‘No, I am too busy, too much to do’. Ferrari replied: ‘You send me your best man, I will supply the Lambrusco and Zampone…’” — Modenese wine and the local delicacy of stuffed pigs’ trotters – “…and you do the manufacture, and we’ll get the job done between us”.

At the time, Jano was busy with designs for a 4.4-litre V12 GP car for 1937 – the Alfa Romeo 12C-37. It flopped… Jano was fired.

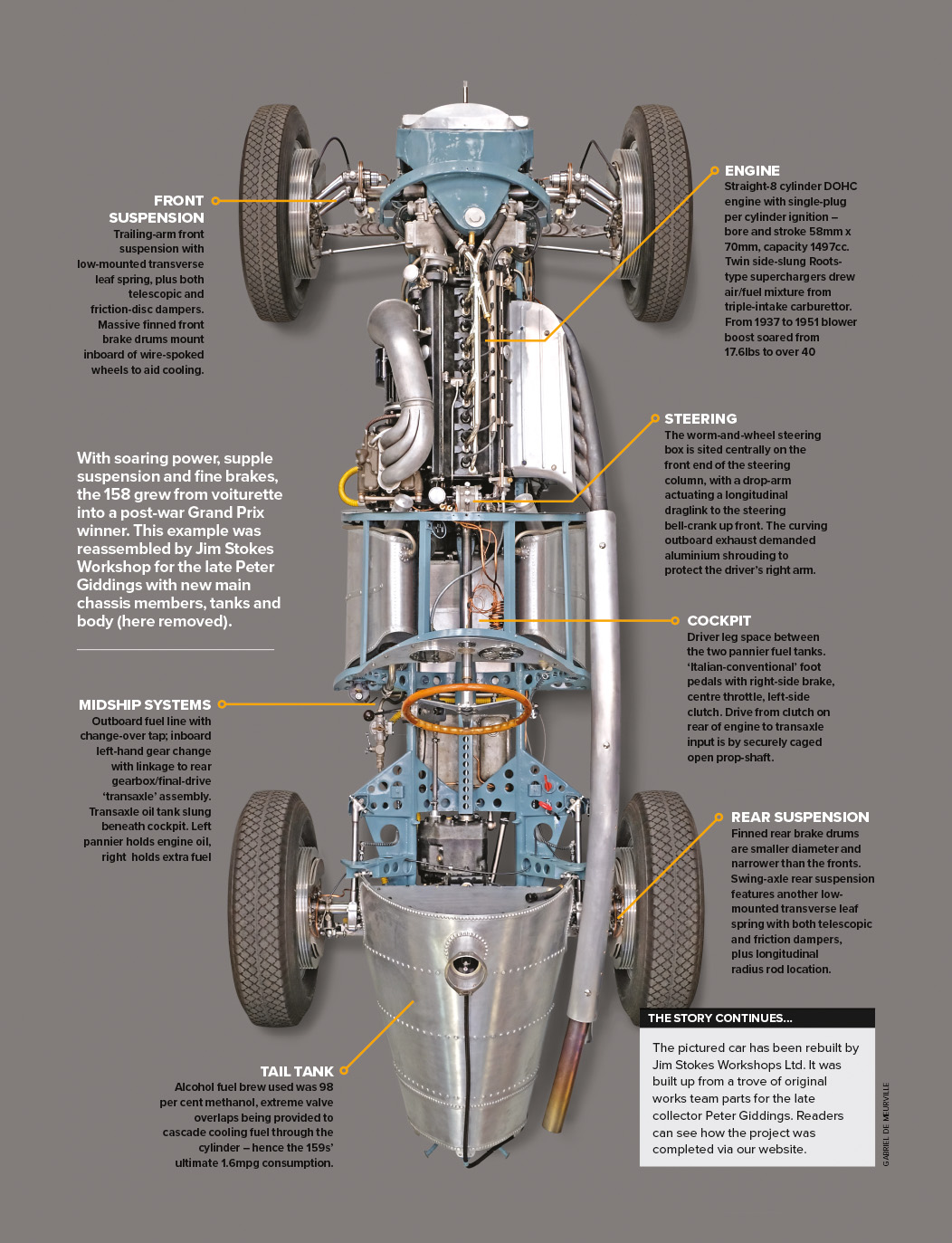

In May 1937, Jano’s No 2 for 13 years, Ing Gioachino Colombo, was posted to Ferrari’s Modena works to produce the proposed new 1500. His task was eased by the fact that the design office at Portello, Milan, was at that time involved in drafting proposals for a new Tipo 316 V16 Grand Prix car for the 3-litre supercharged GP Formula taking effect in 1938. It was logical to design a potent 1500 from one bank of that 3-litre GP engine.

Where the V16’s gear-train drive to the twin overhead cams and other ancillaries was at the rear of the engine, unlike other Alfa eights in which it had always resided amidships, Colombo juggled it to the front of his engine, shortening the crankshaft.

He drew two aluminium block castings, 58mm bore x 70mm stroke providing 1497cc. The crankcase was cast elektron alloy, with steel cylinder liners, and the crankshaft ran in eight main bearings with a ninth subsidiary. Lubrication was dry sump. The twin-overhead cam engine was supercharged by a single-stage Roots compressor, boosting at an initial 17.6psi. In testing at Modena this 1500 developed 180bhp at 6500rpm. By its race debut six months later, Alfa Corse had 195bhp at 7000rpm – 130bhp per litre.

This engine and a four-speed transaxle were mounted in a twin-tube steel chassis with trailing-arm and transverse leaf-spring suspension. A slender body featured a raked potato-chipper grille. Relatively short-distance vetturetta racing allowed ‘just’ a 37.5 gallon tail tank. It would grow, and proliferate with side and scuttle tanks.

Guidotti: “Four cars were built at Modena and virtually completed in every detail there, then the management set up Alfa Corse at Portello; Ferrari came to us as manager and we ran from the factory.” This was a move which Alfa Romeo MD Ugo Gobbato had ordered. Mr Ferrari fitted like a star-shaped peg in a square hole, and he soon opted out.

During 1938 the new Alfettas contested four races, made 14 starts, won twice in the hands of Emilio — brother of Luigi — Villoresi, but had eight retirements. Bearings were a weakness, and for 1939 needle roller big ends were adopted and main-bearing oil feeds improved. The engine now achieved 225bhp at 7500rpm – 150bhp per litre.

At the opening 1500cc Vetturetta race of 1939 – at Tripoli – Mercedes-Benz shook the Italians with its late-entry W165 V8s. Villoresi kept the revs down in his Alfetta and finished third; three other Alfettas failed. The cooling system was changed and its working pressure increased. Engine lubrication was again modified, and the cars coincidentally rebodied to virtually their final form. Of four more races that year, they won three. Their drivers included ‘Nino’ Farina, Clemente Biondetti, Francesco Severi and Carlo Pintacuda. But on a black day at Monza – during a press reception – Emilio Villoresi was killed in one of the cars, and during practice at Pescara ’39 Giordano Aldrighetti also crashed fatally.