Lunch with Neil Oatley

He's been with McLaren for 30 seasons and has played a major part in the capture of several F1 titles, yet he's always maintained a low profile...

Howard Simmons

He’s designed several world championship-winning Formula 1 cars, he engineered both Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna during successful title campaigns and the 2017 season will be his 40th in Grand Prix racing, yet for all his achievements Neil Oatley has never courted the spotlight. Formerly McLaren’s chief designer – and today the team’s design & development director – Oatley says his preference for a low profile is partly a consequence of his own shyness, but more because he has always felt F1 to be a collective effort. “Even when I started, when teams were much smaller,” he says, “you needed good people to prepare and build the car. Winning was never down to just one or two individuals.”

And there has been no shortage of success. He was race engineer to Clay Regazzoni when the Swiss scored Williams’s breakthrough F1 victory at Silverstone in 1979 and headed McLaren’s design team from the MP4/5 chassis of 1989 to the MP4/17D of 2003 (working jointly with Adrian Newey from the MP4/13 onwards, in 1998). That period embraced a world title for Alain Prost, two for Ayrton Senna, a brace for Mika Häkkinen and 67 Grand Prix victories.

A man of deeds, then, rather than words – so it’s time to redress the balance. It complements his understated personality that, given free rein to choose a restaurant, Oatley selects London House, West Byfleet, a purveyor of fine food in unpretentious surroundings adjacent to the local railway station. Run by former McLaren chef Ben Piette, it charges £32 for a two-course lunch. Neil selects pea velouté topped with cream and Parma ham curls, followed by a stilton and cauliflower pancake dressed in French beans, the whole washed down with sparkling water and an espresso.

“New Cross Stadium was quite close to home when I lived in London as a young boy,” he says, “so I went there early in the ’60s to watch stock car racing and, sometimes, speedway. It was right next to The Den, Millwall’s football ground, but sadly like most speedway stadia in the London area it eventually disappeared.

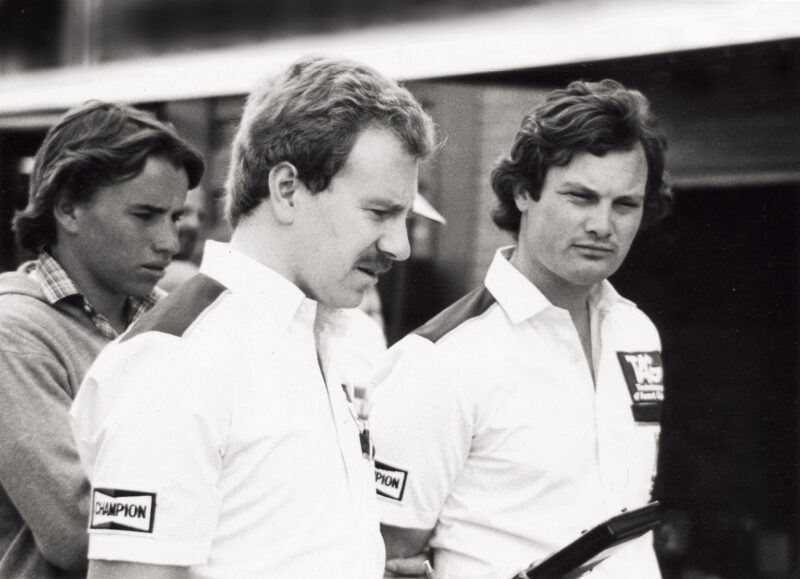

Oatley (with clipboard) looks on ahead of Clay Regazzoni’s landmark Williams win, Silverstone 1979

Motorsport Images

“I’ve had an interest in racing for as long as I can remember, though – I recall watching the Oulton Park Gold Cup on TV in 1961, when Stirling Moss won in the four-wheel-drive Ferguson. Even then, aged seven, somebody would buy me a copy of Motor Sport every month, which helped spur my interest at a time when there was very little racing on TV, and one of my uncles used to race an Elva Courier at grass-roots level.

“The first circuit race I attended would have been The Guards Trophy at Brands Hatch, August 1962. It was one of those typical British summer days, tipping down with rain for five minutes, then bright sunshine immediately afterwards, and Mike Parkes won in his Ferrari 246. The memories remain vivid, but I think that always happens when you visit somewhere for the first time. Very shortly after that my family moved to Kent and we were only seven or eight miles from Brands, which came in very handy over the next few years. My father was in the army and took part in a military parade there when the circuit hosted its first world championship Grand Prix in 1964. I recall being absolutely distraught that he wouldn’t take me with him, which obviously he couldn’t, but at the time I didn’t really understand why. I finally experienced F1 for the first time at the 1965 Race of Champions – I was standing on South Bank and witnessed Jim Clark go off while Dan Gurney was chasing him, one of his very rare errors.”

Being about 45 minutes by bike from his new home, Brands Hatch soon became a weekend staple for Oatley and a couple of like-minded friends – and he recorded some of what he saw in a notebook. “Even when I was very young, aged eight or nine, I was attracted towards the design element of cars and would make small sketches. These became more complex as I grew older and I think that did influence my direction in life. I guess I was formulating a plan from an early stage and eventually I was lucky enough to be able to push ahead with it.”

Nowadays British universities offer many motor sport-themed degrees, but options were rather more meagre as the 1970s dawned. Loughborough was one of very few with a specific automotive engineering course, so Oatley duly enrolled. “I didn’t have a job lined up when I graduated,” he says, “but I attended an interview on my way home at the end of term and was asked if I could start the following Monday. That was with a small engineering company in Chesterfield – they made dynamometers and other testing equipment for cars and bikes. It was a good place to learn and you had to pull your weight from day one, rather than it being like an apprenticeship. That was a handy initiation into the engineering world, during the long hot summer of 1976, and I stayed there until I joined Williams.

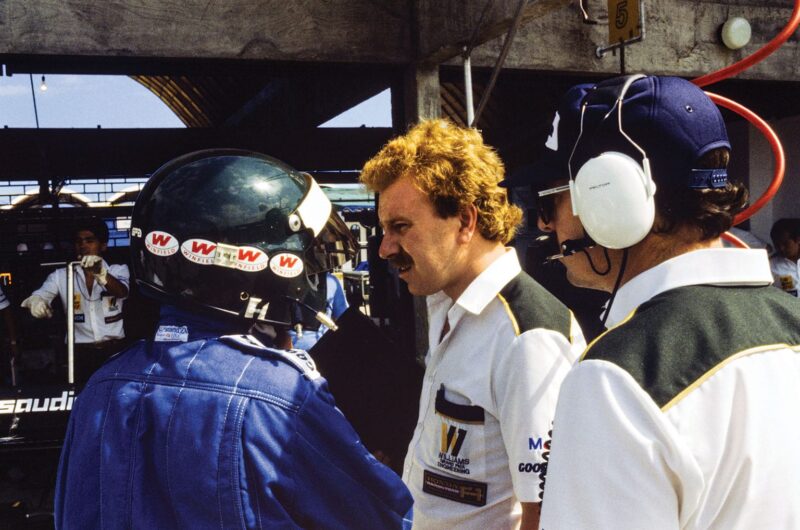

With Frank Dernie 1979

Motorsport Images

“That came about because I saw an ad for a junior design engineer in Autosport. Ever since leaving Loughborough I’d been applying for jobs with volume racing car manufacturers such as Royale and Lola, but without success. When the Williams opportunity came up, Frank didn’t have a particularly good reputation and the company was still tiny – I had to take a significant pay cut from my job in Chesterfield! – but fortunately I made a decent impression on Frank. There were two candidates in the running: Patrick Head wanted to take the other one, but Frank chose me and pulled rank. At that time, in September 1977, Patrick was the team’s only other designer. I joined the day after the Italian GP and became employee number 13. There were two people in the machine shop, but that apart pretty much every other department seemed to have one person. The race team had a couple of mechanics and two truckies – it really was a tiny operation. When I joined, people were asking me, ‘Why on earth are you going there? It’s a dead loss.’ My view was that I was only 23, and if things didn’t work out I could always go back to what I’d been doing before.”

Williams had started afresh as an F1 entrant after selling his previous, largely unsuccessful team to Canadian businessman Walter Wolf. In 1977 he ran a customer March chassis for Belgian Patrick Nève, but by the time Oatley joined Head’s first Grand Prix car, the FW06, was starting to take shape.

“Patrick had done some work, mainly on the monocoque,” he says, “and obviously in those days you bought a lot of parts rather than designing them yourself – the radiators came straight from a VW Golf, for instance, and we used a standard Hewland gearbox. For the exhausts, we had a bloke who would come in and bend the pipes as required. It was my job to do detail work on Patrick’s designs – I can’t claim to have had much engineering input, but it was a fantastic way for a young, inexperienced person to learn. Patrick would handle all the tricky stuff and I’d do everything else – a great general education. Then again, the whole landscape of the sport was very young then – most people seemed to be in their 20s or 30s. That has changed enormously, because nowadays there are lots of older people involved – me included.

“Patrick was a fantastic mentor and gave me a great deal of support. He was very patient and a good, practical engineer who was very unselfish when it came to passing on knowledge. Although the FW06 was at the genesis of the wing-car era, it was quite an old-fashioned design in that it was simple, light and very stiff, but still relatively competitive in Alan Jones’s hands. Even with just two of us working on the car, we had it ready to test before Christmas – it was designed and manufactured in a very short period of time, nothing like the way things are today, even though we had very little equipment. Saloon car racer Dave Brodie [who had lunch with Simon Taylor, Motor Sport August 2014] was a team director at the time and found this old printer, which we subsequently used. One day I noticed a sticker that said it had been made in 1910. That was the kind of stuff we worked with.”

Oatley began to gain first-hand track experience during testing of the FW06. “I went to Jarama in the spring,” he says. “I travelled down with the truck and we arrived on a Sunday, bizarrely while the Spanish motorcycle GP was taking place. We drove into the middle of all that, then spent Monday sorting out the barriers – quite a few of which were very loose. I spent three days there, then attended one other test at Paul Ricard. That was mostly a tyre evaluation for Goodyear, which paid teams for testing different compounds. Frank loved that – we got so many pounds per mile, which was quite a profitable exercise for a team of our stature. We covered about 750 miles and kept going until nine in the evening, by which stage it was quite dark, to earn a bit extra.”

Jaques Laffite worked with Oatley for two seasons

Motorsport Images

And then, when Head began to turn his mind to the following season’s FW07 during the summer, it fell to Oatley to engineer Jones’s car for a few Grands Prix. “I don’t think that would happen in this day and age,” he says, “because in reality I had zero experience.”

The presence of rugged Aussie Jones played a significant part in Williams’s evolution as a serious F1 force. “Frank and Patrick had initially tried to sign Gunnar Nilsson,” Oatley says, “but when he turned them down it actually proved to be a very good thing for the team. Alan was an excellent second choice, a great character and a very good fit. He had a terrific rapport with Frank and Patrick, as everyone knows, but that lifted the whole operation. He wasn’t an engineer and never pretended to be, nor was he shy about getting blind drunk. That wasn’t particularly unusual for drivers in those days, mind, because it was simply a different world. Going to the gym wasn’t one of his priorities, but although he wasn’t fit in modern terms he had tremendous strength and stamina. That made him particularly good in races, because he could keep up a fantastic pace from start to finish without any performance drops.”

The FW06 had showed promise, Jones running second in Long Beach until his front wing collapsed, then finishing second in the penultimate race of the campaign at Watkins Glen, and Head’s fully ground-effect FW07 made Williams a truly competitive force as it expanded to two cars in 1979.

“The team had by now added Frank Dernie to its engineering strength,” Oatley says, “and Patrick didn’t want to attend all the races. He and Frank were to work with Alan, while Clay Regazzoni had joined us from Shadow and I’d look after him. That was really nice for me, because during his Ferrari days about 10 years earlier he’d been one of my teenage heroes. I’d never met him before and he was every bit what I’d expected from things I’d read in the press – a nice guy. He was much more interested in racing than testing or qualifying, so didn’t always start from as high a position as he might have done, but he drove some great races that year.”

The high point, for both team and driver, came at Silverstone, where Jones dominated until his car broke and Regazzoni picked up the pieces. “A cracked water pipe caused Alan’s retirement,” Oatley says. “We used to modify the standard Cosworth pipes to run higher up in the car, to improve underwing airflow, and this one hadn’t been welded very well.

“The rest of that race remains a bit of a blur. As I’m sure anyone who’s run a GP car will tell you, you are wracked with nerves because your mind keeps going over all the things that might go wrong – as they often did at that time. Clay had quite a big lead after Alan dropped out, so he was just keeping to a set pace. Obviously it was an unbelievable day for Frank, given all that he’d been through. I think that’s the only time I ever saw alcohol pass his lips – whisky, rather than champagne, if memory serves.”

Engineering Senna to the 1990 world title

Motorsport Images/Sutton

Jones would win four of the next five Grands Prix, lifting himself to third in the final standings and putting Williams second in the championship for constructors. In 1980 he and the team would win both titles, with new team-mate Carlos Reutemann contributing one victory and seven podium finishes.

“Carlos was quite an unusual character,” Oatley says. “At the start of a race meeting he’d focus on different parts of a lap, splitting it into four quarters. He’d start by concentrating completely on the first bit, drive that as quickly as he could, then cruise for the rest of the lap while thinking about how he might have done it better. On the pit wall Patrick would be going apoplectic, because Carlos was about 10sec off the pace, but gradually he’d move along to deal with other parts of the circuit and then, once he was happy that he’d worked them all out, he’d suddenly do a lap that was quicker than anybody else.

“Although he didn’t try to engineer the car, he had a very technical mind. He could probably go back through a whole season and tell you which ratios he’d used at every corner of every circuit. He had a fantastic memory for set-ups and so on, but perhaps lacked a bit of self-confidence whereas Alan was very self-assured.”

In his second year with the team, the Argentine went to the seasonal finale – a new venue for F1, on a track laid out within a car park at Caesars Palace, Las Vegas – with a one-point championship lead. He qualified on pole, but then sank almost without trace in the race. He dropped to sixth and fifth place was enough to give Piquet the first of his three world titles.

“I honestly believe that was down to the self-confidence thing,” Oatley says. “About a week beforehand he seemed to have convinced himself that he wasn’t going to win the title. Also, we’d switched from Michelin to Goodyear during the season [at the French GP, after the American company did a U-turn on its pre-season withdrawal] and he was very unhappy about that, because he had a big thing about tyres and felt very comfortable on Michelins after previously using them at Ferrari. The majority of Carlos’s points that year were scored early on, using Michelins, and I don’t think he could believe we’d done such a thing in mid-season. Goodyear’s wet and dry tyres were of a different diameter at that stage, too. It rained in Montréal and when we stopped to change tyres during the race we also had to adjust the ride height. Carlos sat in the car laughing, because he thought it was such a ridiculous situation.”

Reutemann stuck with the team in 1982, but after two races decided to quit the sport. “To this day I don’t know why,” Oatley says. “He was well connected politically in Argentina and perhaps had an inkling that the Falklands War was about to commence, but I don’t know that for certain.”

Having commenced the season with newcomer Keke Rosberg, recruited to replace the retired Jones, Oatley worked for one race with Mario Andretti and the balance of the campaign with Derek Daly, whose results didn’t reflect the stellar form he’d shown in junior racing. “I struggled to find a mechanical set-up that suited Derek’s style,” Oatley says. “Keke had tremendous athletic ability to drive and control a car on the edge of a big accident, yet always come out on top. Derek wanted something slightly more comfortable and we never managed to give him a car that allowed him to showcase what he could do.

1984 debrief with Williams, with Laffite, Head and Rosberg

Motorsport Images/Sutton

“When Keke joined, incidentally, his contract stipulated that he must pay his own travel expenses. He’d sit in economy on long hauls – probably at the back, so he could have a fag while playing backgammon with his mates.”

For the next two seasons Oatley worked with Jacques Laffite – and also, from 1984, Honda, his first acquaintance with the firm whose engines would in future power his championship-winning McLarens.

“Honda had been with the Spirit team in 1983,” Oatley says, “and I recall looking under its awning at Monza. There were three engines completely stripped down and the guys were trying to find enough parts to build one good one from among all the bits that had failed. It was a tiny operation at that stage, and nothing like as big as it became. Honda’s arrival in F1 coincided with the electronics explosion. With a Cosworth car, a good bloke could make a wiring harness in about a day, but suddenly you had 10 times as many wires and sensors. It was a culture change that could be traced back to Renault’s arrival in 1977. It took a few years for everybody to adopt turbos, but I always wonder how things might have evolved if Renault hadn’t appeared. Would Honda and others have been tempted in if Renault hadn’t started the turbo trend?

“Jacques? He was a fun guy to work with and everybody on the team loved him. He could be laidback, though. At Dallas in 1984 [where the Frenchman turned up in his pyjamas, as a protest against the proposed 7am Sunday morning warm-up], the race was due to start early to avoid the worst of the afternoon heat. Jacques had wandered off somewhere and had forgotten that little detail. He reappeared just in time and we were still tightening his belts as everyone else was setting off on their warm-up lap…”

Late in 1984 Oatley received an approach from former Williams colleague Charlie Crichton-Stuart, to enquire whether he’d fancy working as designer for the new, US-funded Beatrice Haas Lola team, which was due to make its debut during the summer of 1985 prior to a full championship assault the following season.

“I was completely happy at Williams and loved all the people there,” Oatley says, “but I felt this was a chance to stand on my own feet rather than be guided by Patrick all the time. And again, I was still young enough that I was sure I’d be able to get opportunities with other teams if things didn’t work out. I decided to take the risk and see what happened.

“Ross Brawn and I moved from Williams to Haas at the same time and Adrian Newey arrived in mid-1986. He was by then reasonably well established as an engineer and would have been a great boost to the team, but the project folded before he was able to exert any influence There was a boardroom coup at Beatrice. The firm’s president had been a big racing fan, but he was replaced and nobody else there was really interested.

Oatley began his McLaren career as Prost’s race engineer – and designed 1989’s title-winning MP4/5

Motorsport Images

“I got to know Adrian better later on, when he joined me at McLaren. He’s exceptionally bright and is often cited as an aero genius, but to me he’s also an extremely good engineer with a tremendous mechanical understanding of how components work. If something goes wrong in the field he’s a very good bloke to have around – much more than a specialised aerodynamicist.”

By the time it became apparent that the Haas F1 project would fold after a single full season, Oatley had already received an approach from McLaren. Initially he would be working alongside respected former Brabham designer Gordon Murray – although he didn’t realise it at the time. “As I prepared to start in my new role,” he says, “I went to visit Ron Dennis at his home and was surprised when Gordon opened the door – the first I knew anything about him joining. Obviously we knew each other from the paddock and we had common interests in motorbikes, music and what have you, so we’d always got along very well.”

Oatley started McLaren life as Alain Prost’s track engineer in 1987-88, the final phase of F1’s original turbo era, and between events focused on design, his first full-car project being to modify one of 1988’s MP4/4 chassis to take Honda’s new, naturally aspirated V10s so that the team could test it for several months ahead of its formal introduction. And in the background there was the simmering feud between Prost and team-mate Ayrton Senna.

“Alain was very straightforward,” Oatley says, “and certainly at a different level from other drivers with whom I’d worked. Up until the mid-1980s you relied on intuitive engineering, but then data started to become available and it changed the way we analysed the car. And then Ayrton arrived, which raised things to yet another level. Alain had a good sense of humour, but Ayrton didn’t really share that kind of mindset until later, when Gerhard Berger came along and educated him.

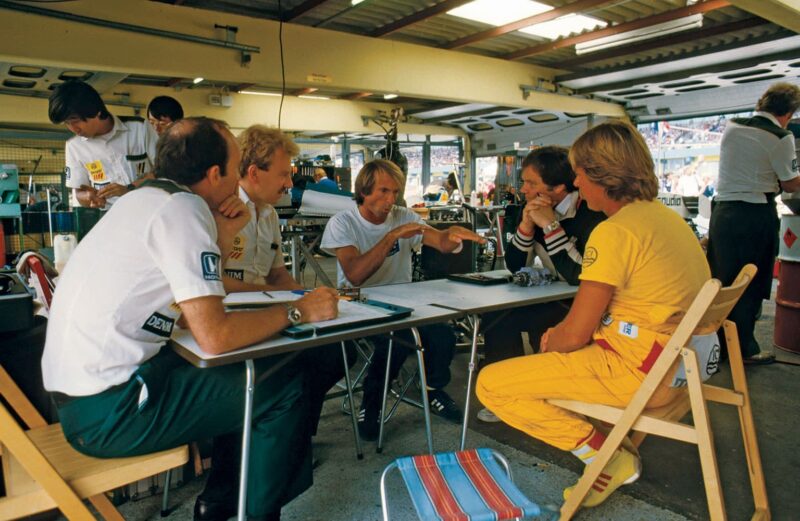

With Steve Nichols, Gordon Murray and Alain Prost, 1988

Motorsport Images/Sutton

“But the atmosphere within the team wasn’t as bad as you might imagine – Ron Dennis was very good at handling stuff like that. I think he had both drivers on the phone constantly, trying to manipulate things to their advantage, but he didn’t let the rest of the team worry about it. We just got on with our jobs. For the first part of 1988 things were fairly cordial between Alain and Ayrton, but then there was a hint of trouble at Estoril [where Senna aggressively edged Prost towards the pit wall at about 170mph, as they started lap two]. The mind games had started the previous day. Alain was going particularly well and in qualifying, at a time when you could run whenever you liked, he did a stunning lap after about 30 minutes, then pulled into the garage, jumped into the transporter, changed into T-shirt and shorts and returned to the pit wall, looking at Ayrton. I think the manoeuvre on Sunday might have been a bit of payback.

“Things really deteriorated after Imola in 1989 [when Senna broke a pre-race agreement that whichever of them led into the first turn would be allowed to stay ahead during the race’s early stages]. After that the two of them didn’t speak for the rest of the year. I remember sitting in the engineering office and the debrief would involve me, Ayrton’s engineer Steve Nichols, Gordon and the two race drivers. Ayrton would ask me things about Alain’s car and Alain would speak to Steve about Ayrton’s, but they didn’t talk directly to each other.”

Prost won that year’s title in the Oatley-designed MP4/5 and then departed for Ferrari, after which McLaren assigned Oatley to work with Senna.

“I don’t think he’d forgotten that I’d been Alain’s engineer,” he says, “but we got along fine. Ayrton elevated things in terms of commitment and technical interest. We’d been used to a quick chat with drivers and then, an hour or so after the session, they’d be gone. Ayrton had used Honda engines with Lotus, before he came to us, and had a good rapport with its senior engineers. Sometimes he’d talk to them for an hour before he came to talk things through with us. That was the world changing into an embryo of what we have today.”

Oatley always watches GPs on TV these days, but attends relatively rarely. This is from Silverstone in 2014

Motorsport Images

After coming so close to winning the title with Reutemann at the decade’s dawn, he ended it by working with back-to-back world champions, although he wasn’t on hand to savour either moment because by that stage of the season he’d be based in the factory, focusing on the following season’s chassis.

“In 1990,” he says, “I lived in Newbury and remember driving to the McLaren factory at about 3am to watch the Japanese GP live – and of course it was all over after about 30 seconds [when Senna purposely torpedoed Prost’s Ferrari at the first turn, putting both out of the race and in the process securing himself the title]. We still had Gerhard Berger leading, but then he ran over debris from their accident and by lap two our race was done. I never spoke to Ayrton about that subsequently, but didn’t really need to. I was fairly certain I knew what had happened.”

That would be Oatley’s final year as a hands-on track operative, because F1 was heading in a fresh direction.“In the early days I’d work as a race engineer, then return to the office on a Monday to become a designer,” he says. “I’d do that for a week and a half, then go back to track engineering. But as more data became available and analysis increased, the days of chief designers being track engineers became rather obsolete – teams started to become arranged in a new way and there was a greater distance between the racing and design departments. By the early 1990s you needed a different type of engineer to run the cars, someone who could focus 12 months of the year on data. My natural inclination was more towards designing and making things. I embraced the new technology, but teams were getting bigger and I had other people to handle that stuff for me.

“The Ford-engined MP4/8 was the first car we designed completely electronically, in 1993. After that drawing boards began to disappear. That was probably one of the most interesting engineering years because we were still allowed quite a lot of gadgets. We designed a simple active-ride system in about two months, with layout sketches, and then the really clever people did the electronics and it was on the car by the start of the following season.”

Oatley continued to attend races until the mid-1990s, as chief designer, before moving into the more factory-based role he holds to this day – and that has changed the nature of the relationship he’s had with McLaren’s drivers. There have been some wonderfully gifted racers on the team’s books during the past 20-odd years, including Mika Häkkinen, Kimi Räikkönen, Juan Pablo Montoya, Fernando Alonso, Lewis Hamilton and Jenson Button, but the close relationships of the past are no longer possible. “We do get to know them in different circumstances, away from the circuit,” he says, “but I am relatively distant from the drivers nowadays. Of the guys we’ve had since I stopped engineering, I don’t think history gives Mika the credit he’s due for his form in the late 1990s. He had an incredible ability to drive quickly while very rarely making mistakes. I felt Kimi was similar when he was with us, too.

“I wasn’t at Suzuka in 1998, when Mika clinched his first title, but spoke to [special projects engineer] Tyler Alexander, who was. He told me Mika had trouble sleeping the previous night and seemed convinced he wasn’t going to win, to the point that he didn’t really want to get into the car on Sunday. But then once the race started he drove faultlessly and disappeared.

“Although I don’t travel to races any more, I’m still glued to the TV on Sunday afternoons to see how all the relationships are playing out. I went to a lot of Grands Prix in the 1960s and 1970s and lots of people my age look back on that as a golden era, but there were some incredibly dull races.

“You might get one or two good contests per season, but if that type of racing had been on TV it wouldn’t have appealed. It wasn’t unusual to have 30sec gaps between the first three cars with the fourth a full lap behind – and reliability used to be appalling.

“It is very different now, though I’ve often thought we should go back to a closer grid – certainly two by two rather than one by one, so there’s more chance the field might shuffle itself a little on the run to the first turn. The worst races are the ones in which the field takes off in grid order – and then stays that way.”

Could he ever have imagined the manner in which F1 would evolve, when he pitched up at Williams’s old Didcot factory as junior design engineer. “No way,” he says. “It’s a very different environment now, by necessity. When I started at Williams we had two engineers, when I joined McLaren there were eight or nine of us and now we have about 160. It used to take about a week to design a wishbone, but now it takes several because they are a lot more complex. The most mentally rewarding periods were probably when you could design something yourself on the drawing board, give the sketches to the guys who’d make it and then bolt it to the car to see what happened. Nowadays you’re investing incredible effort into relatively small lap time gains. Go back 40 years and a decent change might be worth half a second or so.

“It would be nice to have more freedom in today’s regulations, but there are limits in terms of car speed. We also owe it to the people watching not to spend half a million pounds on a new front wing that looks very similar to the previous one. You have to do it to be competitive, unfortunately, even though nobody in the grandstands can tell the difference.”

If a fledgling engineer from a small firm in Chesterfield walked into this environment today, would they struggle to land a job?

“If I’m honest,” he says, “the answer is probably ‘yes’.”