Lunch with... Hans Stuck

As the son of a pre-war Auto Union ace, racing was in his blood. Today, ‘Junior’ is a cult hero in his own right

James Mitchell

It’s intriguing how often sons of racing drivers become racers themselves. In Formula 1 Nico carries on the work of Keke, as did Jacques for Gilles – although so far only Damon and Graham have achieved a World Champion son of a World Champion father. Sometimes grandsons follow to make a third generation, or brothers and cousins. The remarkable Andretti and Unser dynasties spring to mind.

In the campsites around the Nürburgring Nordschleife, they’ll tell you about Die Stuckrennfahrerdynastie. Hans Stuck von Villiez drove for Auto Union in the 1930s, winning Grands Prix and dominating mountain hillclimbs. Including the interruption of World War II, his racing career lasted 39 years. His son, Hans-Joachim Stuck, beat even that. When he hung up his helmet this year his cockpit time, covering F1, endurance racing, GTs and touring cars, had spanned 43 seasons. Now his two sons, Johannes and Ferdinand, are busy GT racers in Europe.

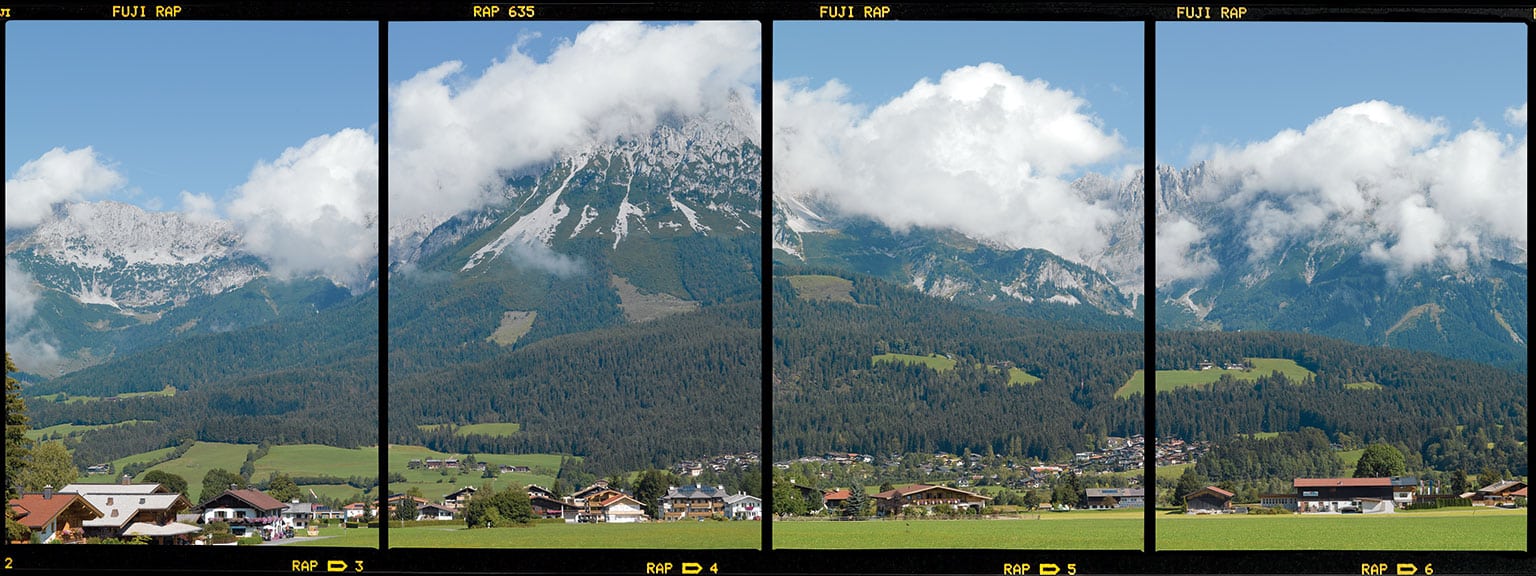

Hans-Joachim is known to the German-speaking world as Strietzel, an untranslatable nickname referring to a type of local honeycake. At his christening an aunt exclaimed that the plump new baby looked just like a Strietzel. The plumpness left him early on – he became and still is a tall, rangy individual who often had difficulty fitting his height into tight cockpits. But the name remained. Although he has a place in Florida, where a close neighbour is former team-mate Derek Bell, his main residence is in Austria. It’s a breathtaking mountain-top house he had built 10 years ago close to some of the Tirol’s most fashionable ski resorts, made almost entirely of wood harvested from Porsche-owned forests in southern Germany. A central staircase curves around an immense tree trunk that supports the whole house, and panoramic windows on all sides reveal jagged peaks that march from horizon to horizon. That’s where he welcomes me, once I have received the slightly grudging approval of his enormous Rottweiler/German Shepherd cross. He shows me historic photographs and trophies from his father’s racing days, including a tiny working musical box in delicately worked filigree silver, part of the spoils of victory in the 1934 Swiss GP. The basement garage cut into the mountainside contains great cars from his own career, from his first BMW 700. Then we bump down the mountain in his runabout for the rough local roads, a Land Rover Defender.

Lunch is in a village gasthof where his banter with the owner shows they are old friends. He takes only a small plate of thinly-sliced raw steak and apple juice. His conversation is machine-gun rapid, punctuated by uproarious laughter and realistic car noises as he reloads with the next anecdote. Even in the already straight-faced world of 1970s F1, with Stuck a practical joke was never far away. His fellow German Rolf Stommelen was, says Hans, rather serious. “On a race weekend while he was having dinner, a group of us stripped his hotel room. Took out all the furniture, the bed, even the light bulbs, rolled up the carpet. Hid it all away. When he and his lady go up to bed they open the door: only bare floorboards.” Snorts of laughter between gulps of apple juice.

In the 1920s the young Hans Senior had a farm south of Munich. The farm’s milk was sent into the city every day by train, but Hans realised profits would be better if he delivered it himself. “He got an ancient Dürkopp and drove it like a maniac to Munich every morning. His friends teased him about his old car, so he bet them he could drive up a steep local mountain pass, backwards, faster than they could in their cars, forwards. He switched the gearbox around so he had one forward gear and four reverse gears, and he won the bet. So he got the taste for car sport, and he started to do hillclimbs seriously.”

Noting his success, Austro-Daimler put him in a works car. For them he won a string of hillclimbs and championship titles, and embarked on a circuit career. Then Austro-Daimler pulled out, so Hans bought an SSKL Mercedes, hurling the big car up the hills he now knew intimately and becoming 1932 Alpine Champion. He also shipped it to South America and won the Brazilian Hillclimb title.

Stuck had got to know Austro-Daimler and Mercedes designer Ferdinand Porsche, and when Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933 Dr Porsche was ordered to outline his plans for a world-beating Grand Prix car – a rear-engined, 4.4-litre supercharged V16. Stuck was present at the meeting, and was the first to test the new P-Wagen. In March 1934 he set world speed records at AVUS, and in July at the Nürburgring he scored Auto Union’s first major victory in the German GP. The next day he was obliged to drive the winning car on the public roads from Berlin to the Auto Union factory at Zwickau: schools were closed and thousands lined the route to cheer him. He went on to win the Swiss and Czechoslovakian GPs, and would have been European Drivers’ Champion had such a thing existed. He also powered the difficult V16 monster, with its rear swing-axles, up the steep, narrow passes of his beloved hillclimbs, winning another Mountain Championship.

The funds set aside by the Third Reich for motor sport domination were split between Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz. According to the late Chris Nixon’s superbly-researched work Racing the Silver Arrows, Alfred Neubauer of Mercedes offered to double Stuck’s retainer if he would swap teams. Stuck talked the proposal over with his friend Rudi Caracciola, who as the star of Mercedes not surprisingly persuaded Hans to stay put. But, while Stuck was the only one of Auto Union’s 16 drivers to remain with the team throughout their six seasons’ racing, he would never again experience the same level of success. He won the 1935 Italian GP at Monza, was second in the German GP to Nuvolari, and led at AVUS until a rear tyre exploded at 180mph. In 1936 he had big accidents at Pescara and at Monza, and in 1937 his best finish was second to Hermann Lang at Spa. In hillclimbs he continued to dominate, but at the end of 1937, by which time the brilliant Bernd Rosemeyer was Auto Union’s new star, he was fired.

Stuck’s own explanation for this was that he allowed Rosemeyer to see his contract. Rosemeyer felt he was being underpaid, and asked Stuck’s advice. Each Auto Union contract contained a clause forbidding the signatories from discussing it with anyone else, but Stuck, sympathising with young Bernd’s plight, told him he was going out for a walk, and hinted where in the house his contract could be found. A few days later Auto Union finance director Dr Bruhn told Stuck that Rosemeyer had asked for more money, and he knew why. Stuck’s contract was terminated.

A few weeks later Rosemeyer was dead, killed in a 270mph record attempt on the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn, and soon Stuck was back in the team. He was third in the German GP, and was lying second to Nuvolari at Monza when his engine failed. And he was European Mountain Champion again. But there were no more race wins up to the outbreak of war.

March co-founder Max Mosley talks to his driver in 1975, his second season in F1

Motorsport Images

When peace returned Stuck raced an 1100cc Cisitalia, and built the AFM F2 car with Alex von Falkenhausen, working in the garage of Stuck’s house in Garmisch. He was third in the 1950 Solitude GP, but once again there was more success on the hills. He raced a Porsche Spyder in South America, winning on the new Interlagos track, and in ’57 he started a relationship with BMW. He took class wins in its elegant but heavy sports car, the 507, and in the little 700 coupé he claimed the German Hillclimb title at the age of 60.

In 1948 Hans had married his third wife, Christa-Maria. Their son Hans-Joachim was born in 1951. “I wouldn’t have been interested in cars without my father. When I was a toddler I would hang around the garage while my dad and von Falkenhausen worked on the AFM. One day they couldn’t find the small spanner they needed to adjust the valvegear. They searched high and low, but in the end they put the bonnet back on, started the car up – and Wheee! this little spanner shot out of the exhaust pipe. I was in a world of my own, and I’d pushed the spanner into the exhaust, thinking I was helping to prepare the car. When I went with him to his races and hillclimbs, I got the smell, I got the infection, and from then on my only target was to be a racing driver.

BMW M1 Procar series was Stuck’s favourite

Motorsport Images

“My father taught in the race driving school at the Nürburgring, and I was just nine years old when he first let me drive a couple of full laps in one of the school cars, seat right forward, sitting on a cushion. After that I did a lot of laps. Another instructor was the BMW tuner Hans-Peter Koepchen. When I was 18 he said to my father, ‘I’ve watched your lad. I want to put him in for a race.’ My father was worried, he knew a racing driver’s life can be very hard with injuries and money, but it was too late already. There was a 300km single-driver race on the Nordschleife, and I did it in a Koepchen 2002, no seat belts, no overalls, just shirt and jeans and open-face helmet. I already knew the track, every kilometre. But each time I went over a big jump the throttle cable came undone. I had to keep stopping to reconnect it, but I still finished third in class. Then Koepchen put me in the Nürburgring 24 Hours with Clemens Schickentanz. We won it outright. It was so different in 1970: no catering, no motorhomes, nowhere to change or shower, no girls to massage you. The state of the art then was sitting on a camp chair in the old pits for 24 hours, eating chips and drinking Coke.”

Hans also sampled the hillclimbs at which his father had excelled. “They were fun weekends. When you stand around for 15 hours and do five minutes of racing, there is plenty of time for funny stuff. And it’s good training, because in a race, if you make a small mistake, you can recover. In a hillclimb, if you make the smallest error you can never get the time back. You have to be very precise, starting on cold tyres, trying to memorise the track. Some drivers would sneak out in their road cars on Thursday and Friday to do extra practice. They’d paint black bars on the white reflector posts by the road, braking points, two stripes for second gear, three for third. So when it got dark we’d go out with white and black paint and change them all, removing some stripes, adding others.”

More and better touring car drives began to come his way. In 1971 he scored wins in BMW 2800, Simca 1100 and Opel Commodore. He nearly had a second win in the Nürburgring 24 Hours, starting from pole and holding a big lead until, with an hour left, the engine blew. For 1972 Jochen Neerpasch, Ford of Germany’s racing boss, signed him to drive the works 2600RS Capris. He and Jochen Mass won the Spa 24 Hours, and three more wins at the Nürburgring and a string of other victories earned him, at 21, the title of German Champion.

Chris Amon shared BMw 3.0 CSL at Le Mans in 1973

Motorsport Images

“For 1973 Neerpasch left Ford to go to BMW, and he wanted to take me with him. He was one of the first to focus on how cockpit concentration is allied to physical fitness, and in January he summoned all the team drivers to fitness training in Switzerland – gym, cross-country skiing, weightlifting. Some of us weren’t too sure about this stuff. Chris Amon was in the team, and he was anything but fit. We had to report to the factory in Munich and pick up brand-new BMW road cars, then drive to the hotel in St Moritz. Of course it developed into a flat-out race on those twisty mountain roads: eight cars started and only five arrived. Neerpasch was furious. I did the season with the CSL coupé, usually with Chris in the longer races. We won the Nürburgring Six Hours, but we had bad luck everywhere else. At Kyalami Jacky Ickx and I were leading the class, and a front wheel fell off. I came into the pits on three wheels and a brake disc, Screeech! They rebuilt the front corner, and we finished the race.

“I’d had my first single-seater race at Hockenheim in 1970, in an F3 Eifelland March, and I didn’t enjoy it. I didn’t fit in the car, and I got caught in somebody else’s accident.” A car spun mid-pack and several others piled in. Hans’ March flew, landed on its nose between a post and a startled photographer, and caught fire. In 1971 he had a single F2 ride in an Eifelland Brabham at the ’Ring, but was taken off by Vittorio Brambilla. But in ’73, with March now using the BMW engine in F2, Neerpasch organised with Max Mosley half a dozen rides for Hans. He didn’t finish in any of them, but he ran near the front often enough, particularly at the ’Ring in the wet, to show he was comfortable in a single-seater now. “I stuck up above the rollover bar, I had trouble fitting my knees under the dash, and I had to cut the toes off my boots to work the pedals. Otherwise I was OK.”

This led to a works March F2 drive for 1974. Then, days before the first F1 round in Argentina, Jean-Pierre Jarier walked away from his March seat and signed for Shadow. Overnight Hans was summoned to Buenos Aires to squeeze into the March 741. “I had never even sat in an F1 car before. My first try was in official Friday practice. I was going through a fast fourth-gear right-hander thinking, this is pretty good, and Eeeeowww! Niki Lauda’s Ferrari came past on the outside. I was 10 seconds off the pace. So I went to see Carlos Reutemann. It was his home circuit, so I thought he was a good guy to ask. ‘Excuse me, my name is Hans Stuck, and I am new to F1. Can you please tell me how to drive round this circuit?’ We did 10 or 12 laps in his road car and he gave me a lot of good advice, which was very nice of him. On Saturday my times were much better, and in the race I was running 11th when the transmission broke.”

Hans Stuck Snr, Auto Union driver and king of the long mountain climbs

Motorsport Images

At Kyalami Hans qualified seventh and finished fifth, and a month later he was fourth at Jarama, making his mark in what was at best a midfield car. In F2 he won four rounds and had three more podiums, but was pipped to the title by consistent team-mate Patrick Depailler. He was also scoring more wins in BMW’s touring cars. In all, he did 31 events that season.

“For 1975 Teddy Mayer approached Jochen Neerpasch, who was pretty much acting as my manager now, to see if I could drive for McLaren in F1. But Jochen wasn’t keen, because BMW were going to race touring cars in America, and he persuaded me that would be better: maybe I was wrong, but I have no regrets. I had a great time in the US, and my team-mate was often Ronnie Peterson.

“Ronnie and I got on so well. Our relationship was just perfect. But I knew if I could beat Ronnie’s times I could ask Neerpasch for more money. So we just tore the cars up, like throwing bread to the birds. At Brands Hatch we shared a 320 turbo. After a couple of laps it started to rain and I lost it, chucked the car over the guard rail and into the woods. It was wrecked, bodywork gone, parts hanging off. I walked back to the pits and told Ronnie, and we jumped into our road cars and drove away, Ronnie to his place in Maidenhead and me to Heathrow to catch an early flight home. Monday morning Neerpasch’s secretary called: ‘Mr Stuck, please come to the office at once.’ I was living in Munich then, so I got there in 10 minutes. Jochen was sitting there, face as long as a metre. ‘Where were you yesterday? They stopped the race because of the rain, we got the car back, there was only bodywork damage, we fixed that in minutes. We put the car back on the grid for the restart, and we had no drivers. You’re lucky that both of you had left, because if it had been one of you he would have been fired. You’re both fined 10,000 marks for leaving the circuit without permission.’ I got straight on the phone to Ronnie. ‘Listen, you won’t believe this. This is the best story of all!’”

Hans continued to drive for March in F1 when his BMW schedule allowed. He qualified seventh at the Nürburgring, ahead of reigning champion Emerson Fittipaldi and eventual winner Reutemann, only for his engine to fail on lap three. Two weeks later, in the chaotic rain-sodden Austrian GP, he qualified fourth and ran near the front until he slid off into the fences. He did a full F1 season for March in 1976, finishing fourth at Interlagos and at Monaco. But the race he remembers most fondly that year is Watkins Glen. “I qualified sixth, but had a clutch problem at the start and got away almost last. At the end of lap one I was 23rd. By half-distance I was fifth, and that’s where I finished, with Lauda’s Ferrari and Mass’ McLaren about five seconds in front of me.”

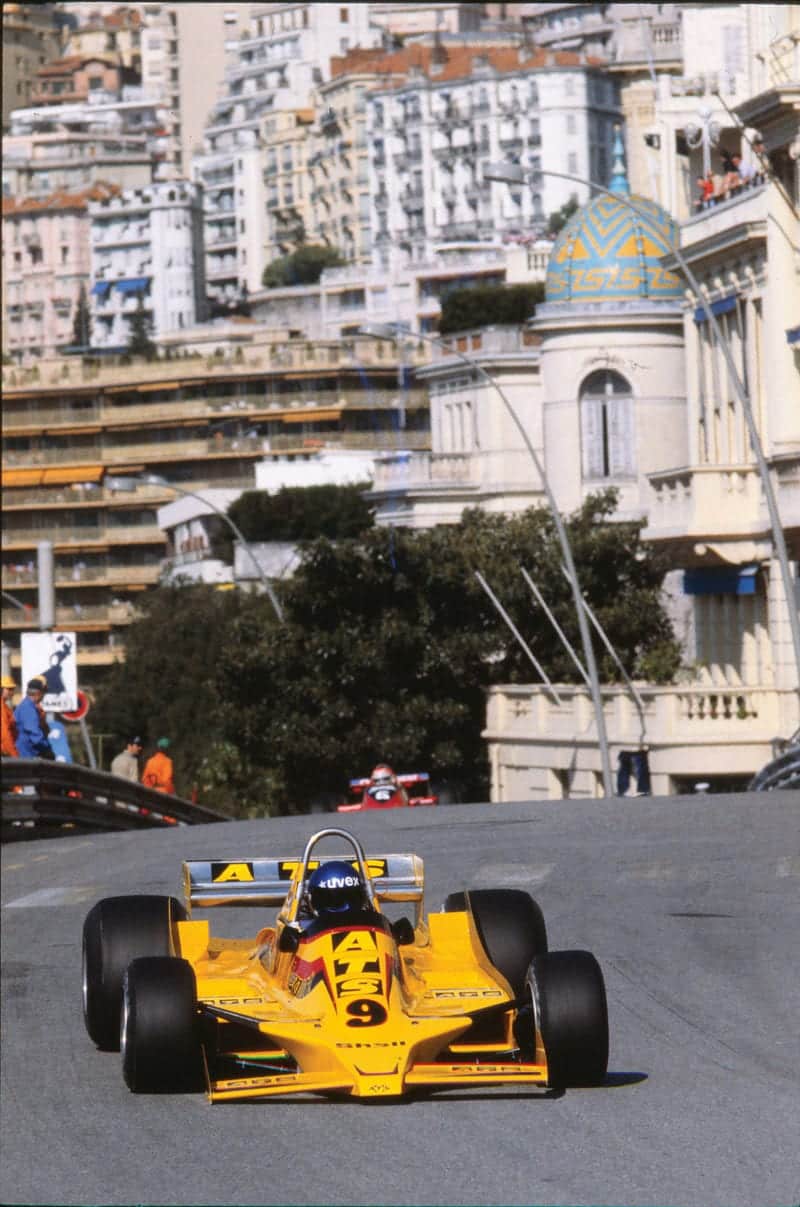

An unhappy season with ATS was Stuck’s last in F1

Motorsport Images

In March the following year Brabham’s Carlos Pace died in a light plane crash. “At once a lot of talk, who will be John Watson’s team-mate? The flat-12 Brabham-Alfa looked like a winner, and the next race at Long Beach was less than two weeks away. Then Bernie [Ecclestone] calls me in. ‘Do you want to drive for me?’ Of course I say ‘Yes’. ‘How much do you want?’ I say, ‘Last year with Max I earned $80,000. I’m not a rich man, and I need to take care of my mum.’ [Hans Stuck Sr had died, aged 78, a few weeks before.] At that moment the phone rings on Bernie’s desk and he picks it up. ‘Ah, Arturo. Si, si. How much? Thirty? OK, I’ll get back to you. Ciao, Arturo.’ Then he says, ‘That was Merzario. He will race for me for $30,000, plus some money for the points. You want it, or not?’ ‘I’ll do it,’ I say. I sign the contract for $30,000, and five days later I’m in a Brabham-Alfa at Long Beach.

“The next month, after qualifying at Monaco, we’re having dinner, all in a good mood because Wattie’s on pole and I’m fifth on the grid, four-fifths of a second slower. And Bernie says, ‘Now we’re friends, I’ll tell you something. In my office when we were talking about money, it wasn’t Merzario on the phone. It was my secretary in the next room, I told her to call me.’ That’s Bernie.

“I always got along with him extremely well. When you work for Bernie he is very demanding, which is good for me: I’m always better when I’m put under pressure. That season there were some problems with the car and the engine, but I finished ahead of Watson in the championship. I was on the podium at Hockenheim and Zeltweg, and in the points at Jarama and Zolder and Silverstone. Then at Watkins Glen I qualified on the front row. Before the race Bernie said to me, ‘Next year Lauda comes to us from Ferrari, and Parmalat are our new sponsors. Parmalat only want winners. You win this race, and you’ll stay with me.’ John Watson had only won one Grand Prix then, and Bernie had to choose between us for 1978.

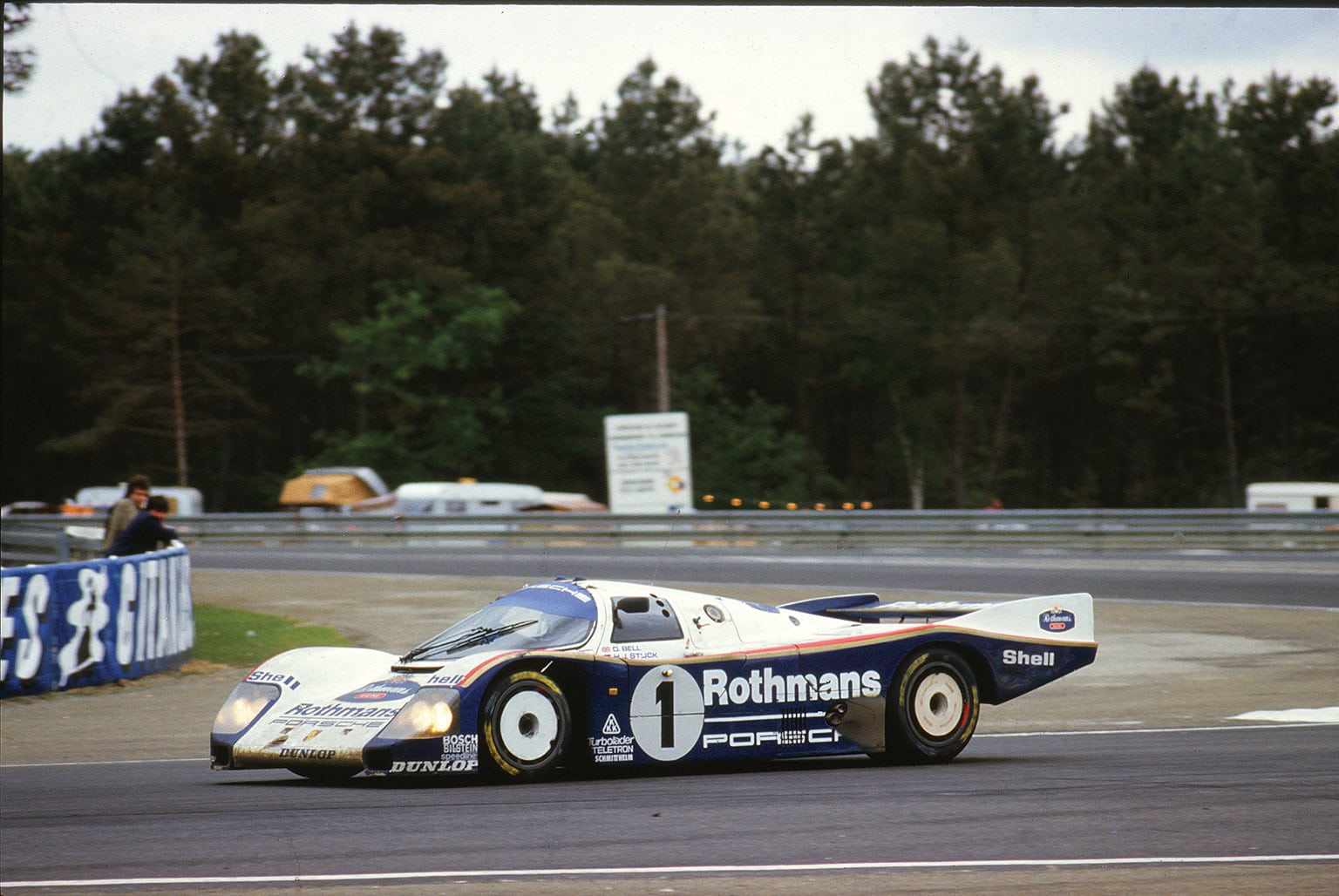

Back to back Le Mans wins with Derek Bell and Al Holbert were highlights in Porsche 962s (below)

Motorsport Images

“It was raining hard when the race started. I out-accelerated James Hunt’s McLaren, which was on pole, and pulled out a good lead. I felt very comfortable. Then on the third lap the clutch cable broke. But it wasn’t a problem because gear changes were easy without the clutch if you got the revs right. Then the rain stopped, the track started to dry, and I began to think I’d have to stop for slicks. How could I get out of the pits without a clutch? While I was trying to work that out I slid off the road and into the barriers. Babaaam. That was that. For 1978 Brabham had Lauda and Watson.

“So I went to Shadow. Not a great season, I only scored points at Brands Hatch, but my team-mate was Clay Regazzoni. A fabulous guy, good driver, very fast, we had some great fights. He had the right mentality, and we both liked to have fun. When he arrived at a circuit for a Grand Prix, his first question was never, ‘Where is the car?’ It was always, ‘Where are the girls?’

“For 1979 I joined ATS, Günther Schmidt’s team. It all seemed good: me as sole driver, spare car, lots of testing, good money. The car wasn’t so bad, but Schmidt always wanted to control everything. He had a problem with himself, a terrible temper, he was always angry. Once he didn’t like the new front wing the guys had fitted. He told them to take it off, and then he jumped up and down on it in the pitlane to destroy it. He’d made his money out of ATS wheels for road cars, and at Monaco he said, ‘Now we must race on ATS wheels.’ We thought he must know what he was doing, because he was a wheel manufacturer. After 30 laps I was up to eighth ahead of the Brabhams of Piquet and Watson, and along the waterfront a wheel broke, flew in the air, bounced off a lamp post, and Kersplosh! into the water by Schmidt’s yacht, in front of all his guests.

“In the last race of the season, at Watkins Glen, I came through from 14th on the grid to finish fifth. Those two championship points were the first ATS had ever scored, and it got Schmidt into FOCA, which was worth a lot of money to him in transport to the races and so on. But he didn’t say, ‘Good job, Hans.’ He was angry: ‘Why didn’t you finish fourth?’

“ATS was the end of F1 for me. I knew I could get good drives in sports and touring cars, earn a good living, have more fun. I did Le Mans 18 times, the Daytona 24 Hours 16 times, all the other long-distance races. In 1985 I joined Porsche.” Hans drove the immortal 956/962 Porsches at Le Mans seven years running, winning two years on the trot and scoring a second, two thirds, a fourth and a seventh, a superb record. On six of those seven occasions he drove with Derek Bell, and Al Holbert joined them for their back-to-back victories in 1986-87. “Whenever Derek was in our car I never had to worry for a single second. Fast, reliable, he didn’t break anything, and very good at adapting if anything was going wrong. Holbert was brilliant too. Two more favourite co-drivers were Thierry Boutsen and Danny Sullivan. I was third again at Le Mans in ’94, and second in ’96, both times with Thierry. He is quite serious, quite Belgian, and I am not so serious, but our sizes in the cockpit were the same, and he was very fast. Danny was with us in ’94, a lovely guy. Who doesn’t like Danny? We used to call him ‘spin and win’.

1977 German GP, and the first of two podiums that year for Brabham

Motorsport Images

“When I joined Porsche Professor Bott, head of development, said: ‘Mass is living in South Africa, Bell is in England, Ickx is somewhere, but you live two hours from Stuttgart. We need you to be on call for development testing.’ I did more kilometres at the Porsche test track at Weissach than anyone, setting up the works cars, setting up customer cars. Norbert Singer was one of the few guys I ever worked with who would build a new car and it would come to the track already very nearly 100 per cent. I learned so much in my years with Porsche. At the races Peter Falk was the perfect strategist, and my engineers were great: Walter Näher and Roland Kussmaul, who was also a very good rally driver. But the first GT1 was a terrible car, because it was almost a normal 911 with a 962 back end bolted on. It never felt in one piece, it was like somebody was sitting in the back and steering, although at Le Mans in 1996 Thierry, Bob Wollek and I brought it home second overall, first in class. The later GT1 was much better, but it was a heavy mother to drive.

“I did a lot of racing in the States. In 1988 Audi sent me over there with the big four-door 200 turbo saloon, massive horsepower and four-wheel drive. With the centre differential we could change the percentage of power front to rear, adapting between street circuits and ovals. We could go from 50/50 to 20/80, which was almost like a nicely balanced rear-wheel-drive car. It was totally cool. In 1990 Audi did DTM, and against Mercedes and BMW I thought we had no chance, but we still won the title because there was so much engineering in the car. Then there was the ITC in 1995, when I drove for Opel. Those cars were incredibly complex: cooling shutters that closed to increase straightline speed, moving weight ballast under braking, self-adjusting rollbars, paddle gears developed by Williams, and you could pre-programme it all to each circuit. Going testing we had an engineer from Cosworth for the engine, another from Williams for the transmission, somebody from Bosch for the ABS braking. At the end of a race you had so much data you couldn’t analyse it all, but when it went right it was amazing. Like on the street circuit at Helsinki, narrow and twisty between concrete walls. I won both heats.”

Hi-tech Opal racer in 1996 International Touring Cars

Motorsport Images

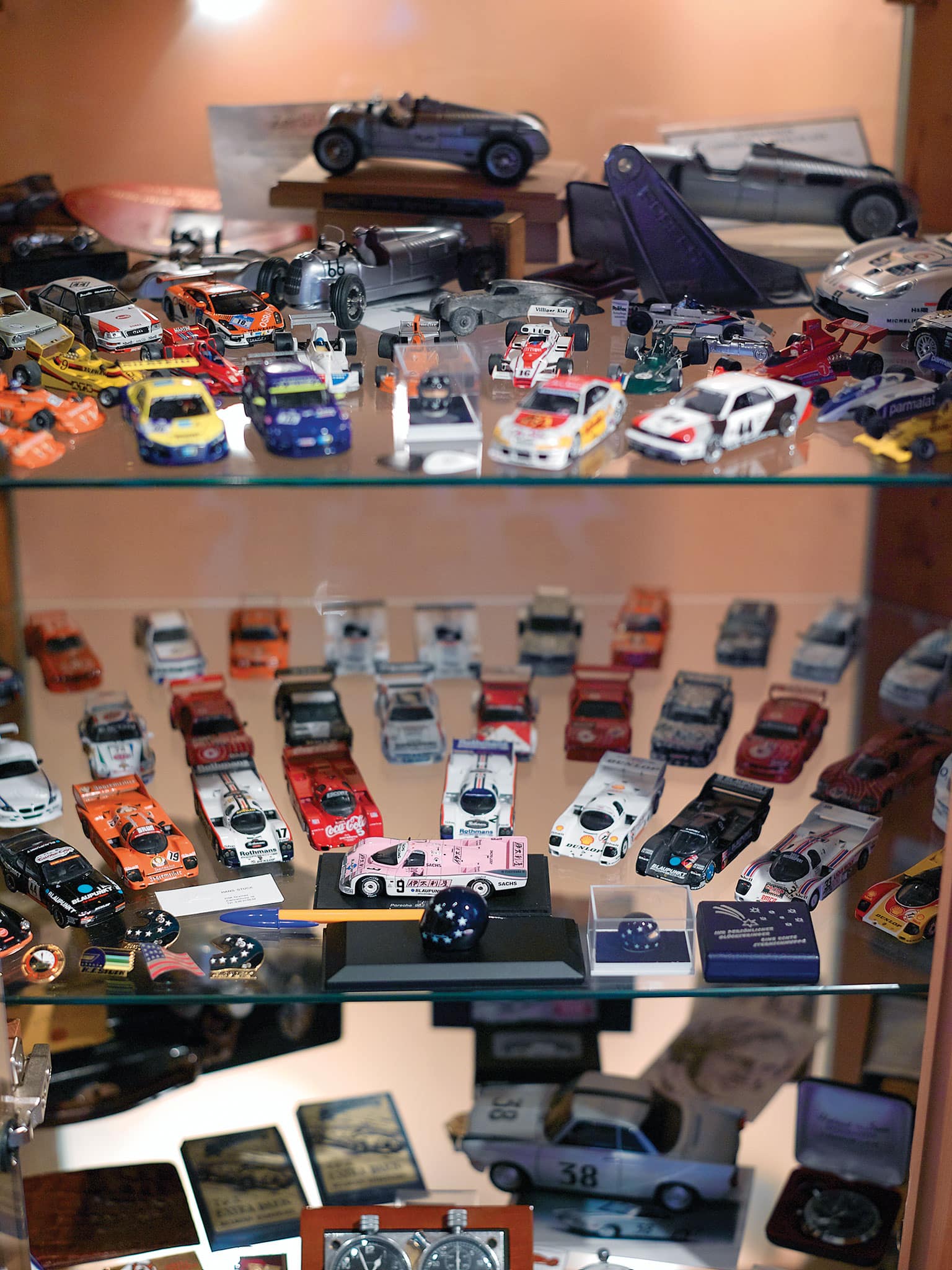

Hans’ favourite series of all was the wild BMW M1 Procar programme that supported Grands Prix in 1980/81. “The best ever, nothing has ever compared with it. A whole field of identical BMW M1 coupés mainly driven by F1 guys, with big prize money so everyone really went for it: the close racing, the noise – open-exhaust straight-sixes, Mmmmm! – it was usually better than the Grand Prix. Neerpasch organised it, he spent a ton of money on it. The five fastest F1 guys from Friday qualifying were put in the works cars to compete with privateers: I was always in a privateer car because at ATS I never qualified in the top five. They were put at the front of the grid, so I could never start above P6. But I won at Monaco, Zandvoort and Monza, and I won the privateer section both years. The second season I was in the Project 4 car run by Ron Dennis. He was my mechanic – ‘Hey, Ron, hurry up, take the front rollbar down a couple of notches’ – but he prefers to forget those days now.

“I raced a special spaceframe M1 with Nelson Piquet in the ’81 Nürburgring 1000Kms, and we were leading when it was stopped by poor Herbie Müller’s fatal accident. I had my worst accident in that car, in the Kyalami Nine Hours. During the night something broke and I hit the wall at 250kph (155mph). The car broke in half, I was sitting with the steering wheel in my hands and the front of the car was somewhere else. Since that crash I have a false nose.”

The stories of 43 years’ racing continue to pour out, always with guffaws and sound effects. Victory in the Nürburgring 24 Hours again, this time with a BMW 320 diesel: “Four-hour stints between refuelling stops, chugchug. That’s how we won it.” Winning the German truck championship: “So much fun. Just the tractor unit, very short wheelbase, 1500 horsepower, constant oversteer, smoking tyres. They weigh 5.5 tonnes, and you sit up high over the front wheels, so it’s hard to feel what you’re doing. The speed limiter is set to 160kph (99mph). Five or six trucks all flat out down the straight inches apart, Rrrrrrrrr!, swapping paint, and it’s all about who’s going to brake last.”

Final race: the 2011 Nurburgring 24 Hours, sharing a Lamborghini with his two sons. It gave Hans an emotional farewell

Sutton

And the abortive Grand Prix Masters series of 2005/6: “I hadn’t driven a single-seater for 15 years, but I loved it. Big tyres, big wings, paddle shift, and all my old friends – Emerson, Merzario, Danner, Lafitte. At Kyalami 16 guys all changing in the same room, going bowling the night before, a pit walk for the crowds and us all signing autographs. This is what F1 should be like. Drivers together, friendly, and for the public. And close racing. Not DRS and flaps and closed motorhomes and all this shit. I shared a pit with Nigel, he was great with the public, then as soon as we started practice he was just like the old Nigel, moaning all the time. Then the race started, and Wheeeoww! he was off. His battle with Emerson was brilliant, he beat him by 0.4sec.”

In 2007 Hans was hired by VW as Motorsport Ambassador, covering all the Group’s brands from Skoda to Lamborghini. “In 2009 I did the Langstreckenmeisterschaft at the Nürburgring, a 10-round series on the old Nordschleife, races of four hours, six hours, 1000kms, and the 24 Hours. Eleven classes, everything from Golfs and Fiestas up to full-race Porsches, 250 cars on the track at once, a real demolition derby. And huge crowds camping all round the track, lots of beer. I came into the Schwedenkreuz in an Audi R8 on a dry track and went into a curtain of heavy rain. I hit the guard rail backwards at 225kph (140mph). They stopped the race because of the weather, so I got second place. It was a big impact, and two weeks later I didn’t feel well. I got on my motorbike and rode 50kms to the hospital. They gave me a CT scan and said I had a blood clot on the brain and I was probably half an hour away from falling over dead. I was there 11 days, longest I have stayed in a hospital. They made two big holes in my skull, and they fixed it. That’s why, look, I have this big dent in my head. But I am not George Clooney, so it doesn’t worry me.

“But I don’t do historic racing. In 1993 I raced the 1973 Mark Donohue Can-Am turbo Porsche 917/30 at Laguna Seca. I love the Laguna track, and I loved that fantastic huge Porsche, so much power, but massive throttle lag. You put your foot down, you count, you keep counting – suddenly Beeeoowahhhh! But after that I made a decision. You drive an old car, tube frame, feet out in front, modern rubber giving more forces on the chassis, who knows if everything is still right. And some people in historics now are really crazy guys. I demonstrate, like Goodwood Festival, but I don’t race, like Goodwood Revival. If you race at all you have to race hard.

“When I drove my father’s Auto Union at AVUS it was amazing. All so heavy, brakes, steering, gearbox. Sitting far forward, close to the wheel, zero ergonomics. How did they do it for a four-hour GP at the ’Ring? I took it up to 145mph, and then I was scared, I didn’t want to go faster. He did 200mph around the AVUS banking, and no crash helmet.

“Since I was nine years old, I have probably driven more laps of the Nordschleife than almost anyone else on earth. When I am bored, like when I was lying in the CT machine having my head scanned, I just drive laps of the ’Ring in my head, every gear change, every apex. My first race was there, so this year I decided the 24 Hours should be my final race. I did it in a Lamborghini with my two sons Johannes and Ferdinand. Our target was just to finish, not to win, because we were against some big teams. At the end of the race I did the last stint. Ferdinand brought the car in, and as I got in I thought, ‘after 43 years, this is the last time you ever race a car’. The commentator must have been talking about it, because as I drove round I could see banners and signs everywhere in the crowd, ‘Goodbye Strietzel’, and ‘Thank You Hanschen’. As the race ended I was crying tears, my sons too, everybody was crying. I was able to end my time as a racing driver on my most beloved track with my two beloved sons.

“I still do some taxi-driving: round the ’Ring in an R8 race car with passengers paying big money for charity, classic rallies like the Mille Miglia. But no racing now, and no regrets. For 43 years the stopwatch ruled my life. Now I only use a stopwatch to boil an egg.”