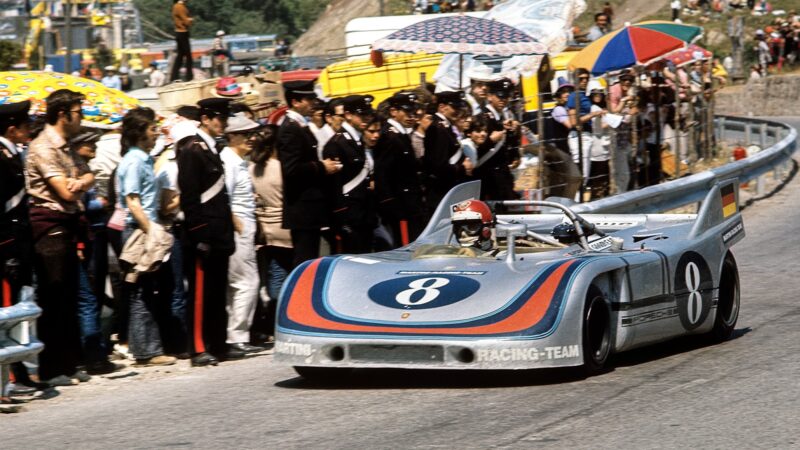

We stop and look back at the start/finish. It’s that shot of Arturo Merzario powering away in his 312P at the start of the ’73 race, crowds spilling on to the road, right there. A gap in the fence allows us to wander through the crumbling concrete stands. A monument to the Targa’s father, Vincenzo Florio, sits shaded under trees and, as is typical of such places, the atmosphere is still, quiet and spooky. Signage is visible, but fading fast, and I’m surprised how neglected these familiar buildings appear. They’re derelict, but at least they’re still standing.

We press on towards Cerda. Here, the roads begin to sweep, but there is still too much traffic to really enjoy the Ferrari. Vic told me the road is now 50 per cent wider than it once was – so single-track, then.

We enter the bustling small town of Cerda and recognise the long high street that climbs slow and straight. At the top it sweeps left then immediately into a long right. Today, traffic restricts us to a crawl. According to Elford, “At the top end of Cerda in the Porsche I was the only one in fifth gear. That was over 170mph.” The street is virtually unchanged and such speeds, attained while locals stood applauding from their doorsteps and balconies, are almost impossible to imagine. This is what I came to Sicily to discover.

My notes from the conversation with Vic read: “After 2km there is a junction – turn left. This is where the wheel of my 907 fell off in ’68. There’s a wall about 10 feet high where spectators were standing. They jumped down and lifted the car back on the road for me.” So this was where it started, the great comeback. Elford, sharing the Porsche with Umberto Maglioli, lost over 18 minutes at this spot, then set off on one of the greatest sports car drives in history, smashing the lap record on the way (see page 60). It’s why his name is still whispered with reverence in these parts.

Elford/Larrouse Porsche 908 set fastest lap at the 1971 Targa Florio but crashed out

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

As we climb away from Cerda, all signs of traffic melt away. The Ferrari is in ‘sport’ mode now and we begin to press on. But there is never a moment’s peace. The stunning, rugged scenery is wasted on us because there is too much to do: second-gear right-hander, accelerate up to third with a tug of the right paddle, flick the left for a satisfying blip down to second (this car makes me sound so much better than I am!) and turn in. And so it goes on. How could anyone remember this?

As the road plunges down into a valley and begins to climb towards Caltavuturo, Vic’s words echo: “I had a photographic memory. Having come from rallying, when I learned the Targa I realised I was writing imaginary pace notes in my head. It was the same as the Nürburgring – I knew every inch.”

On the Targa, drivers could practice weeks in advance on the open roads, but still Redman’s words strike a chord: “I never knew any of it. How do you remember 950-odd corners?”

There was also the road surface to contend with. It’s not very good now, and although period reports explain attempts to resurface sections, it couldn’t have been much better then. Earthquakes, landslips, floods – they’ve all left their mark. Round a blind bend in the low-slung Ferrari and you’re likely to find a cracked step in the surface – perhaps there’ll be a temporary road sign, perhaps there won’t.

Back to Vic’s notes: “Just before Caltavuturo turn left and go downhill. Pass under the autostrada and climb up to Scillato (don’t go into the town, it should be on your left).” Now we slow down for the next town and look for more famous landmarks: Collesano.