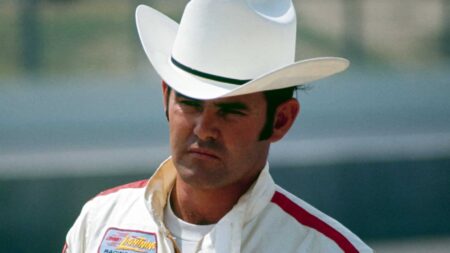

“It was a great era. The drivers and chief mechanics were the guys who figured out what to change. It was a little more dangerous, a little more heartbreak when somebody would get killed. But nobody pointed a gun to our heads and said go out there and take your chances. We did it because we loved it.”

It was engine builder Herb Porter who convinced Mayer to sign Rutherford. “Herb was my benefactor,” says Johnny. “I credit Herb for a lot of my thinking about racing Indy or Championship cars. He set his cars up to run hard and fast, and I got in trouble a couple of times because I didn’t do that.

“Herb was patient with me. He was the guy who told me that at Milwaukee you need to run the outside groove, so that halfway through the race when the track rubbers-in you could start working the outside and passing [cars], and it worked!

“With McLaren, and later with Jim Hall, I did a lot of tyre testing for Goodyear, and you learn a mountain about race cars and the different feel of tyre constructions and compounds. Those things make you a better driver and I was blessed with that at McLaren for seven years and Jim Hall for three years.”

1974 – Indy 500 victory at last: oil-spattered McLaren rolls into Victory Lane

Getty Images

Rutherford recalls how quickly he bonded with Alexander and the McLaren team: “My first race was at Trenton. In practice I banged the fence pretty hard. I thought, ‘There goes your big chance!’ I came back to the pits and apologised to the crew. Tyler put a hand on my shoulder and said, ‘John, if you don’t keep score, we won’t either.’ And that was the basis of our relationship. I knew then that we would accomplish some great things.”

Alexander meanwhile has great admiration for Johnny’s bravery and commitment. “Rutherford had balls as big as an elephant!” he says. “It took us a long time to get him to use his balls, but when he did he was very good. Everybody liked Johnny and when the chips were down the guy was quick. He was in some ways a bit like Andretti. Once you got it right for him he really paid you back.”

“Back then we weren’t limited on the boost. The gauge was pegged and bending the needle!”

Those were days of huge horsepower in IndyCar racing as turbocharging blossomed. There was also plenty of downforce from big rear wings, and lap times skyrocketed through the early ’70s. Into the ’80s more and more restrictions were placed on turbo boost, wings and aerodynamics in general, ultimately resulting in today’s much-reduced IndyCar.

Rutherford was impressive to watch aboard the turbo Offy-powered McLaren M16C/D/Es of 1973-76. Putting his cojones and sprint car experience to good use, he was boldly able to attack the high groove like few others. “The M16 was a forgiving car that was well-balanced,” he recalls. “Gordon Coppuck designed a really good race car and Tyler and Denis Daviss, who was my chief mechanic, knew how to dial it in.

“The first year we ran the M16 the rear wing was huge. It overpowered the front of the car. We went to Indianapolis for a tyre test. It was the first time I’d driven the McLaren and we couldn’t get it to stop pushing the front end. It just understeered and we worked and worked and nothing much happened.”