In this era, the drivers will tell you, the downhill left-handed Pouhon is the most testing corner on the circuit. That said, the exhilaration of Eau Rouge, the impression of being fired out of a cannon, remains, and doubtless Senna would have approved.

Just as it was not by chance that the late Michele Alboreto wore a helmet identical to that of his boyhood hero Ronnie Peterson, so Lewis Hamilton’s bright yellow helmet is an inevitable reminder of Ayrton, whom he revered.

“Actually,” he says, “I think it was the colour of Senna’s helmet that drew me to him in the first place, but of course there was more to it than that.”

I wanted to talk to Hamilton about Senna, because I was interested to know how much, or otherwise, he had been influenced by him – indeed, how much he based his approach to the job of Grand Prix driver on what he had observed, and learned, of Ayrton.

Yellow of Hamilton’s crash helmet pays tribute to Senna

Getty Images

At the time of Senna’s death, in May 1994, Hamilton was only nine years old, but already making his mark in junior karting. “The year before,” he says, “I’d won the British Championship, and got the chance to meet him. I’ll never forget that.

“As a kid, I was drawn to Senna because, for one thing, his driving style seemed to be different from anyone else’s. And he seemed to be a daredevil – well, not a daredevil exactly, but he always went out of his way to… make sure he was at the front. Compared with all the others, he appeared never to be afraid – he seemed to me to have that little bit of an edge.

“I’ve always felt like I had a connection with him, that we’re somehow similar – I do crazy things other people wouldn’t do, and I feel like I have an edge, too. I feel I share something with him – I seem to be able to draw a lot from the way he came across, in interviews, and so on.

“He was such a fighter, that was the thing – I don’t think he was ever one to drive half-heartedly. He was always looking for perfection, and, yeah, he was a warrior – and that was what I loved about him.”

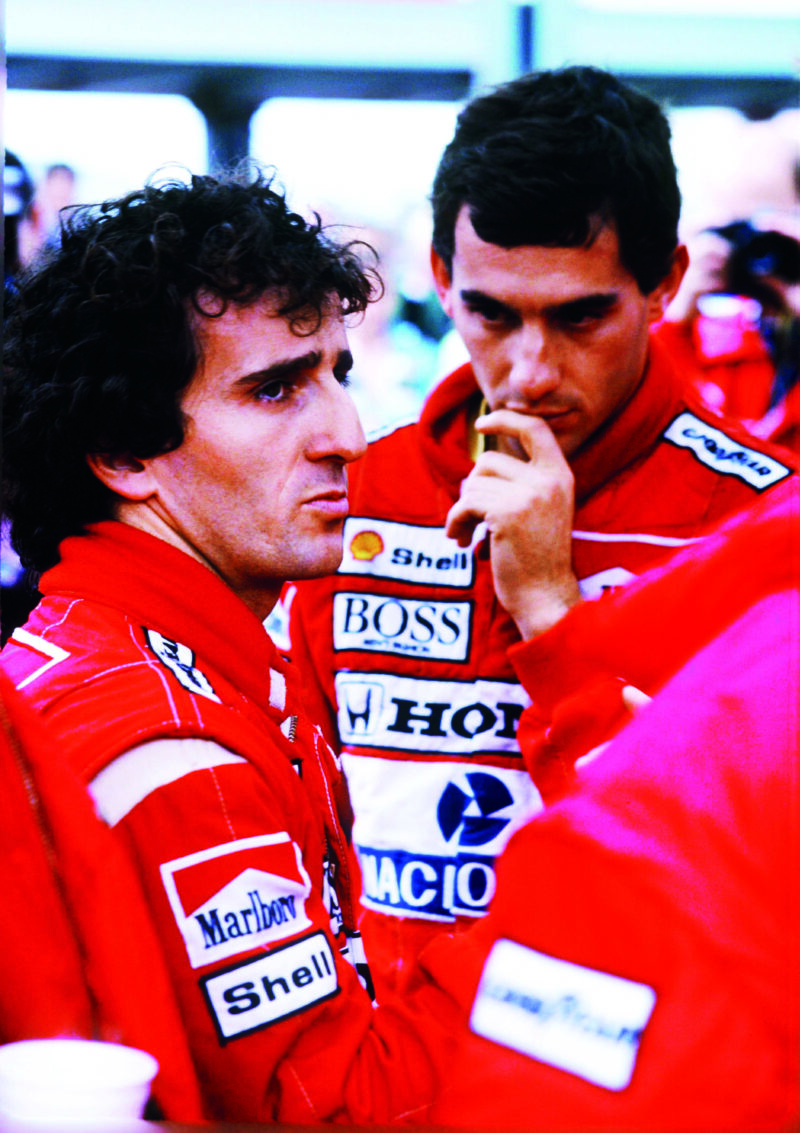

Hamilton appreciates Senna’s “fighter” mentality”

Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images)

Monaco, as Hamilton said, is his favourite circuit, and when he won there in May he said that it meant more to him than any other victory; Senna, of course, won the Monaco Grand Prix six times, a record unequalled by any other driver.

It was Ayrton’s invariable way to go fast in the opening minutes of the first practice session, and nowhere was this more in evidence than at Monaco, where most drivers take time to acclimatise to the circuit’s unforgiving confines, to the nearness of everything. Thirty or 40 minutes into the Thursday morning session, Senna would be maybe two seconds up on anyone else, and even Prost admitted that the psychological effect of that was potent indeed.

“I don’t know what it is, but I’m just able to do it”

In 2007, when Hamilton drove a Formula 1 car at Monaco for the first time, I watched at the approach to Rascasse, and felt an acute sense of déjà vu. Here was a McLaren, with a yellow helmet poking from the cockpit, and, within a few minutes, it was shaving the barriers. When I managed occasionally to catch the times on the PA system, it was no surprise that Lewis was fastest by a street.

“Last year,” he says, “my first laps were a second or more faster than anyone else’s – and I’m talking about the first laps of the whole weekend. I’m faster because I’m getting on it – and I do that because I have to start ahead, because… it’s difficult to put into words… I want to get here, whereas the others start here in order to get here.

“I don’t know what it is, but I’m just able to do it – it’s something about my personality and my ability. You know, being able to relate to someone – when you’re a kid – is something you can’t explain to people, but, as I said, I always felt some… connection with Senna somehow. Of course, the thing is, if you get to the limit quite quickly, it’s hard to go any further…”

Hamilton may base much of himself, and his approach to racing, on Senna, but in one significant respect, I say, he seems wholly different. Ayrton may have had sublime ability in a racing car, but on many occasions he did pull stunts on the track that went beyond accepted – and acceptable – limits, and amounted to blatant intimidation.