“The next year was terrible. I’d been in the car for about half an hour when I suddenly ran into rain down at Stavelot, like a curtain. I couldn’t see anything, the screen misted up and I couldn’t reach it to wipe it. Then there were headlights in my mirror, and this yellow Ferrari P3/4 came by, Willy Mairesse, and he lost it right in front of me and had a huge accident. I was in the middle of changing into fifth, and found myself going sideways in neutral. How I missed all the wreckage I don’t know. But we finished, sixth that year.”

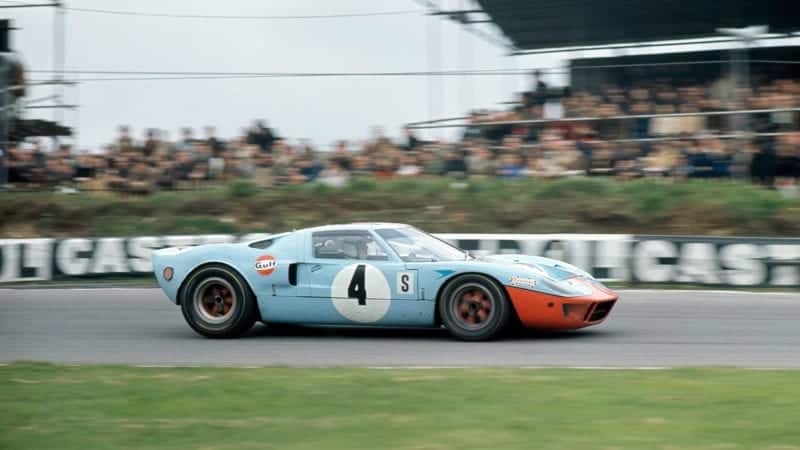

In 1967 Brian travelled throughout Europe racing an F2 Lola for Charles Bridges’ brother David, and a GT40 at Le Mans for Lord Downe. And his efforts in privateer GT40s had been noticed. At the end of the season John Wyer asked him to partner Jacky Ickx in one of the Gulf Mirage GT40s in the Kyalami Nine Hours. They won, and Brian was signed for 1968. Then Cooper offered an F1 drive, and Brian took that too. “It was the start of the Big Time. But it was also the start of difficult times.”

In motor racing back then, danger was ever-present. In April the death of Jim Clark devastated the world. It was followed a month later by the loss of Mike Spence, then Brian’s F1 team-mate Ludovico Scarfiotti, and then Jo Schlesser. Brian and Marion now had two young children, but the money had to be earned. With F1 and sports car deals signed, there was still F2. Following a test at Modena, Ferrari offered a works Dino 166 for the Eifelrennen, on the tortuous Nürburgring Sudschleife.

“We were all in a bunch at the front, Ickx in the other Dino, Kurt Ahrens and Piers Courage in Brabhams, and me. A stone from Ahrens’ rear wheel smashed through my goggles and hit me full in the eye. I flung up my hand and slowed, and peering through one eye I trundled back to the pits. Mauro Forghieri shouted at me: What’s the matter? Put on your spare goggles. I hadn’t got any, so they gave me a pair of Ickx’s, which were dark green for bright sun and not much good for the dark bits. I restarted dead last, and drove like a maniac.” He’d lost 2min 15sec, but he carved back up to fourth place, and broke the lap record. Even without a badly bruised eye, it would have been an astonishing drive, and Forghieri was beside himself with delight.

“At dinner that night he went away, came back, and he said, ‘Bree-an, just now I speak with Signor Ferrari. You drive for us, Formula Due. At the end of the year, Formula Uno’. So I said, ‘No thank you’. ‘What you mean, no thank you?’ I said, `If I drive for Ferrari I’ll be dead by the end of the year’.”

But Brian was going brilliantly for JW, winning the BOAC 500 and the Spa 1000Km with Jacky Ickx, and coaxing a lot of speed out of the unwieldy Cooper. He was third in the Spanish Grand Prix, his third-ever F1 race. Next came the Belgian GP at Spa, and he qualified a strong ninth. On lap seven he had a huge accident at Les Combes. The Cooper smashed into a concrete barrier and slid along it, trapping Brian’s right arm between the barrier and the chassis, and tearing off three wheels before cannoning into some parked cars, landing on top of them and bursting into flames.

Redman (left, in Porsche 971K) goes hammer and tong with Mario Andretti on way to first Daytona win

The Enthusiast Network via Getty Images/Getty Images

“I was one of only about half of the drivers in F1 then who wore seat belts. Otherwise I would have been killed. John Cooper came to see me in hospital and said, ‘What did you do?’ I said, ‘Something broke’. ‘Now then, my boy,’ he said, ‘Don’t worry, you’ll be all right’. On Thursday morning Motoring News came out, and its report said that Redman claimed the steering broke. John phoned the editor and said, ‘I demand a retraction, it was driver error’.” But Autosport came out the next day with a photograph showing the front right wishbone in the act of snapping. Brian was vindicated.

“I used to lie in bed the night before the Spa with sweat dripping down my face”

He was out of racing for the rest of the season. His right arm was badly broken, and steel rods had to be inserted above and below the elbow — which are still there. He played himself back in with the Springbok Series for Chevron the following winter, but the arm was still giving him a lot of pain. He’d just signed for Porsche for 1969, so a specialist in Johannesburg did a radical operation, gluing in new bone taken from his hip. Six weeks later he did the Daytona 24 Hours, sharing a Porsche 908 with Vic Elford.

“I hadn’t told Porsche about my arm problem, of course — just took the sling off when I got to the track. I had to drive on the banking at 200mph holding the wheel with my left arm, and bracing it with my knee. We were out after 12 hours with an engine problem that afflicted all the 908s. That saved me, because I couldn’t have gone the distance. But Porsche never knew.

“Gradually the arm got stronger, and we had a great 1969. There were 10 rounds in the Sports Car Championship. ‘Seppi’ Siffert and I won five of them, including Spa and the ‘Ring. In 1970 John Wyer ran the works Gulf-Porsche 917s, and I was paired with Siffert once more. It wasn’t big money: I was paid £290 per race, and £420 for Le Mans and Daytona. And no prize money. We won Spa again, and Zeltweg, and in the 908/3 we won the Targa. We were leading Le Mans by four laps when Seppi missed a gear passing the pits. Those 917s would only go 200rpm over the limit without blowing, and you didn’t have rev-limiters then. Le Mans is about the only long-distance race that really matters to the public, and I never won it.

“Spa I always found really frightening. Every time I went there I thought I was going to be killed. I used to lie in bed the night before the race with sweat dripping down my face, thinking, this is it.” And yet Brian won the Spa 1000Km four times, and the Spa 500Km as well, winning the European 2-litre Championship for Chevron after a huge battle with Jo Bonnier’s Lola. Ex-JW team organiser John Horsman wrote that Redman was four seconds a lap faster at Spa in the Porsche 917 than either Siffert or Rodriguez. “Yes, I saw that. I rang John and asked him why they’d never told me. He said that if they had, they’d have had to pay me more! People always ask me if I liked Spa. After the race, I loved it. But before the race, I hated it.