When it withdrew from F1 at the end of 1962, Porsche’s stated reason was to concentrate its limited financial and human resources on its road cars and sports car racing. Less charitable observers dismissed this and concluded that Porsche simply couldn’t hack it in F1. It seems a harsh judgement, and yet perhaps there’s some truth in it. Certainly, it must have been a wake-up call to the furious pace of F1 development that the 804 actually fared worse than the stop-gap 718. And watching the Lotus 25 circulate in ’62 must have brought it home to even the staunchest Porsche supporter that it would have to run very hard to catch up.

Porsche’s reason for adopting a flat-eight wasn’t only one of company heritage — its also ensured the lowest possible centre of gravity. But to prevent the engine being too wide, its stroke had to be limited to 54.6mm (bore 66mm), a factor which may have contributed to its reputation for poor torque (113Ib ft at 7450rpm). Peak power was around 185bhp at 9300rpm. Many have blamed the engine for the 804’s relative lack of success, but Gurney didn’t find it a handicap: “I think the power was okay, on a par, really. I’d say it was probably hurting a little on torque, but if you kept it buzzing with that six-speed gearbox it was alright.”

In the search for more power, Porsche’s engineers eventually fitted the engine’s cooling fan with an electronically actuated clutch so that it could be temporarily disengaged by the driver. Supposedly, this was worth nine extra horsepower, but Gurney found this elusive: “Watkins Glen, I think, was the only time I ever used it. There I was draughting someone and I thought, ‘Now’s the time to flip the switch.’” But the hoped for power surge never came. “Nothing! It didn’t seem to make any difference at all.”

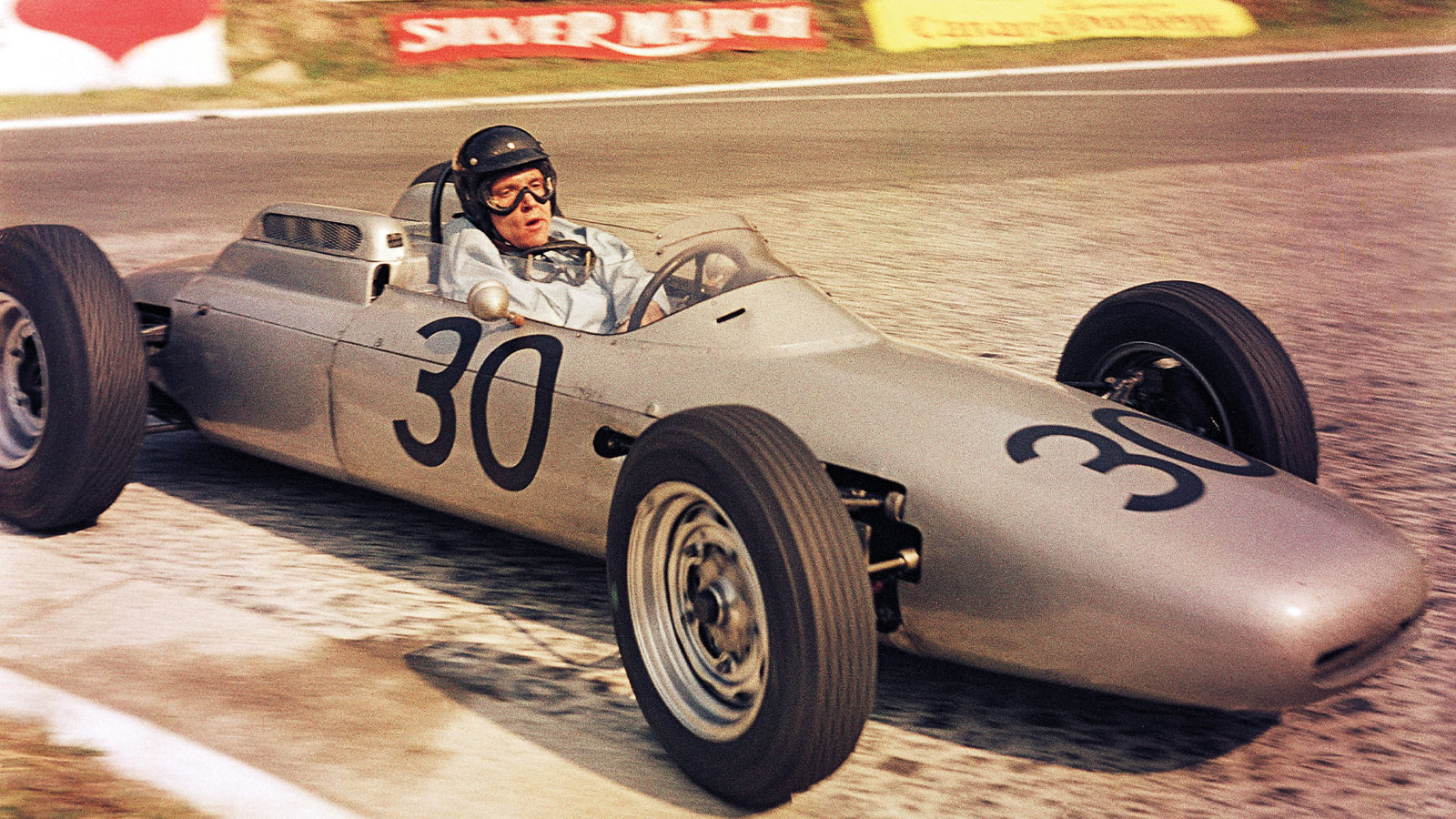

Gurney squeezed into the 804 at Rouen ’62

The lanky Gurney had to insist on changes being made to the 804’s seating arrangement: “The way I was forced to sit for the Zandvoort race, I looked like a giraffe. I was up in the airflow big time.” Porsche made the necessary changes, but Dan had already unwittingly encouraged Lotus to go much further. “I’d bought a Lotus 19, and when I went to have a fitting in the car, again I looked like a giraffe. They said the seat was as for back and as low as it could go, so I asked them to take it out. I got in and slid my backside forward: my knees were up in the air but now I was down in the car. At that moment Colin Chapman stepped into the compartment where we were working, and his eyes sort of popped out. Then he turned round and started designing the 25.”