Auto Union was using two blowers by 1939. Mercedes-Benz had beaten it to this punch in ’38, although those items were in parallel, one per bank on its V12. Both teams were running them in series the following year, a low-pressure unit accepting the charge before squeezing it into its smaller Siamese twin. Auto Union achieved 24psi of boost in this way, an increase of seven from its singleton set-up, and this hiked power from 460bhp to 485 — five up on Mercedes! — at 7000rpm. (Another surprise is that the D-Type ran 10:1 compression, whereas Merc stuck with a conservative 6.5:1.) Of course, drop either V12 into a car weighing the mandatory 850kg minimum minus driver, fluids and tyres and you have a performance that far outstrips, all modern thinking tells you, the road circuits upon which these beasts were unleashed.

This car’s vertical superchargers currently draw from two twin-choke Solex carburettors. However, it is understood that a four-throat, float-less (?), weir-type item was developed for 1939. Entitled the ‘waterfall’, this allowed a jet to draw off exactly what it needed from a chamber topped off by one pump and tapped off at a precise level by another, with any ‘waste’ being recirculated to the main tank. This arrangement also boasted a ram pipe, seen here, that ran underneath the right-hand side of the engine cover before swinging up into and through it.

A colossal backfire — like hitting the brakes — shows that the car is still chilly and grumpy, the methanol freezing around its supercharger inlets. I downshift into first in an effort to keep things ‘on the boil’. The lever is lightly spring-loaded towards the central plane — second, third, fourth and fifth form the usual H-pattern — and its movement is steady rather than rapid. But it exudes quality and solidity, despite a rod linkage that stretches more than 4ft from your right hand to a surprisingly compact, twin-shaft, five-speed gearbox. A dose of double-declutching sees bottom slide into mesh without much of a graunch.

It’s impossible to heel-and-toe, though, which makes things tricky down at the hairpin. But the Lockheed brakes are reassuring. This was another area in which A-U held a slim advantage over cash-rich Mercedes; by 1939, its slotted-backplate, radial-finned, 17-inch drums featured four leading shoes compared to the two of Mercedes. These are operated by a dual-circuit arrangement, the placement of its parallel master cylinders the cause of the wide spacing between throttle and brake. Cold, they grab and pull slightly to the right, locking the fronts once, but they have plenty of feel.

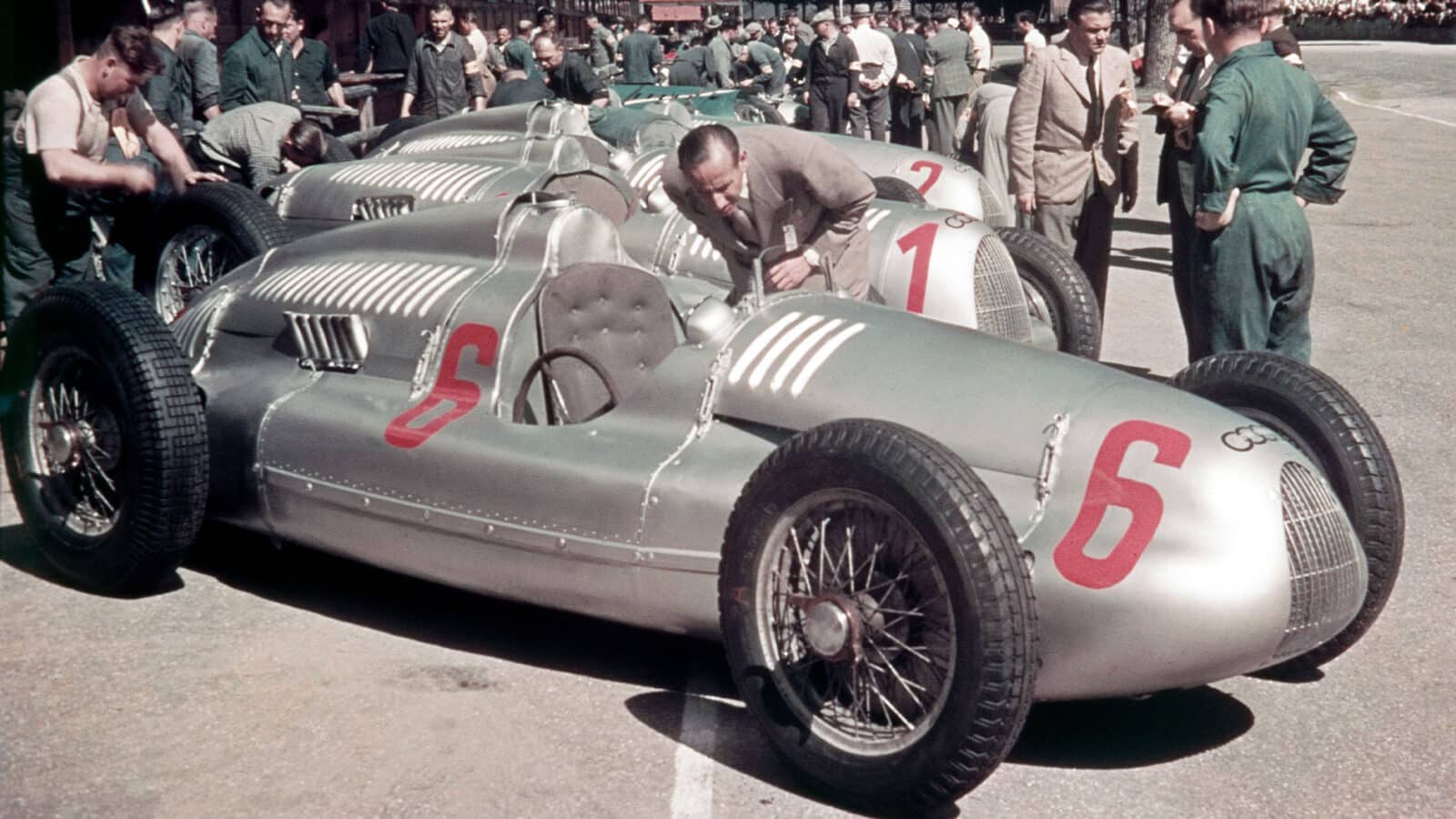

Left to right: Nuvolari, Stuck, Kautz, Hasse and Müller

Getty Images

Not that late-1930s GP racing was about stamping on the anchors and banging down the ‘box. Don’t imagine for a minute that Tazio Nuvolari was the first man on the brakes, but the keys needed to unlock those ultra-fast circuits were high-speed balance and terminal velocity. (This was a time, remember, when the hairpin at Eau Rouge was by-passed because Spa’s organisers were worried that their track was too slow!)

Now bear in mind that the Auto Union C-Type was a snap oversteerer, a wild streak tamed only by Bernd Rosemeyer, a tyro blessed with razor-sharp reactions and unencumbered with knowledge of front-engined racing cars. Lesser mortals struggled, while those others with perhaps the talent to adapt preferred to stick with what they knew — and the larger pay packets — at Mercedes. There can be no doubt that an Auto Union weakness during this titanic struggle was its driver line-up; only in 1935 — with Hans Stuck still on it, Achille Varzi getting to grips with it and Rosemeyer coming through — was the east German team able to match the Three-Pointed Star’s stellar squad. Yes, it almost swept the board the following year, but it relied exclusively upon Rosemeyer — and a major backwards step by Mercedes, the unloved W25C — to do so.