“We were not more intelligent than the others, we were more lucky in that we were also working with the sports car [his dominant 312PB]. With this car we were beginning to understand what it meant to have a large flat surface running close to the ground.”

At back-to-back tests in Stuttgart University’s wind tunnel, it was discovered that the two-seater, with its enveloping body, generated much more downforce than its slender monoplane cousin. Even with its wheels still exposed, surmised Forghieri, an F1 car with a wide, flat top surface would generate greater aero grip than did the current ‘Coke bottle’ cars of Tyrrell and McLaren etc. This would, in turn, mean that a larger percentage of the car’s weight could be sited within its wheelbase instead of hanging a chunk of it over the rear in a quest for better traction. It would also mean that less rear wing would be required, ergo more straight-line speed.

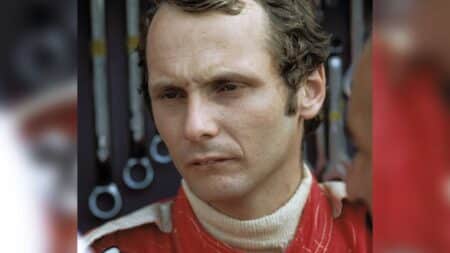

That was the germ. The seed was Spazzaneve (spat-za-nay-vay). The flower was Niki Lauda’s Ferrari 312T. The harvest was seven world titles — three drivers’, four constructors’.

Word of a new Ferrari leaked out even before the 1972 South African GP, round two of the championship. Clay Regazzoni let slip that he and Ickx had assessed a full-width nose at Vallelunga and deemed it an improvement. This was unlike any full-width nose ever seen before: a huge spatula affair, plunging to the floor, gently concave-curving along its leading edge, ailerons at its trailing edge, all bounded by moulded endplates and punctured by two gaping NACA ducts. What’s more, this distinctive proboscis would soon be bolted to a racing car unlike any ever seen before.

Cockpit is cramped, but straightforward

Ian Dawson

Boxy and slabsided, its cockpit conning tower rose from a calm sea of red-riveted aluminium and fibreglass. Head-on, it looked fabulously aggressive, a snarling bulldog, broad-shouldered and purposeful. Unfortunately, the dog analogy continued from side-on, from which angle its forward-mounted (just behind the front wheels) radiators, 93-inch wheelbase and minimal overhangs made for ungainly proportions. Enzo, who still mourned the passing of front-engined GP cars, detested it; Forghieri didn’t care. He had poured his heart and soul into it, pored over the wind-tunnel data, somehow poured a quart into a pint pot. The gearbox still hung out the back, but he was working on that…

Forghieri: “Spazzaneve was a very important car for me – and Ferrari. But it was always meant to be an experimental car. It was a base for me to study aerodynamics. It represented a big change in my mind.”

Its testing began behind closed doors. And that’s how Forghieri wanted it to stay. As far as he was concerned, this car was born in Fiorano and it would die there. This was a project not to be queered by the quirks or qualms of competition.