In contrast, I’m at sixes and sevens with it. And my heart is going 10 to the dozen. Raced by Fangio; wrecked by an idiot. It does not bear thinking about. But it’s all I can think about. We are cruising in second and third gears, taking the photographs you see here, yet this seems fast enough on a damp/dry track. The engine is fantastic — you’d think it had a modern ‘black box’ under its bonnet, so tractable is it — but the steering is leaden, the brakes wooden. How the (green) hell did Fangio do it, be so fast in a car that feels so wilful? My respect goes off the scale.

You are Paul Fearnley (we’ll leave it at that). You have heaps of respect for Fangio, but you have to stand where he once sat in order to lower yourself into his cockpit. Ensconced, there is plenty of width in here — ample for his sturdy frame — but legroom is stunted. The driving position is very armchair: backside over central propshaft, feet not quite dangling, but distinctly splayed, either side — clutch left, brake, accelerator right. Praise be, no confuse-a-novice centre throttle as fitted to many 250Fs.

A studded, wooden-rimmed wheel is a stretch away, but not to the extent of that aesthetic Moss full-arm. Remember that gripping side-on close-up of Fangio? T-shirt, taut bicep, corded forearm. More flex. A wee bit closer to the wheel, I guess.

Dash is simple: rev counter left, oil/water temperature centre, oil pressure (kilograms per centimetre cubed) right. Far right is the four-position ignition switch (twin-spark motor can function on first or second of two magnetos but both are required for racing.)

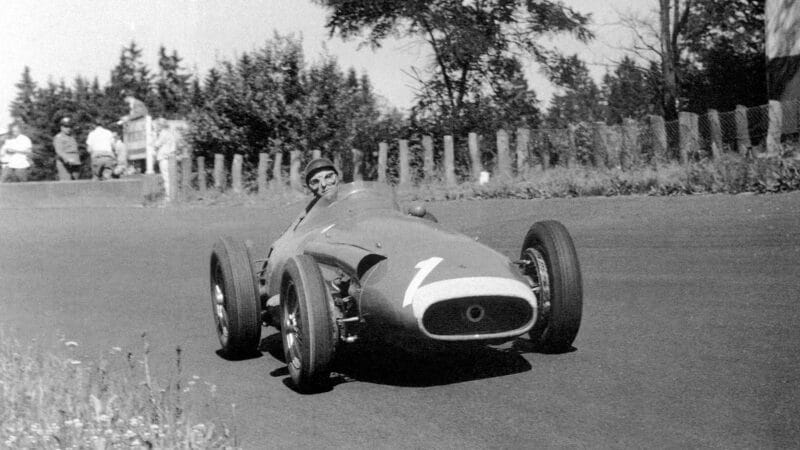

The Maserati 250F: a masterpiece in the hands of Fangio

Yves Debraine/Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

By my right thigh is the metal gear lever. It controls the usual five-speed racing arrangement: first off on a godleg (Freudian typing error), main ratios nestled in the H, reverse blocked by lift-up metal catch. The lever does fall to hand, but only after groping lower than anticipated. Until you settle to ergonomics that scream 1950s, a shift feels akin to a rummage for an unseen item in the footwell.

So, somewhat perched and somewhat cramped, I’m ready for a push-start. Weighty clutch in, second snicked. And heave!

Giaochino Colombo’s reworked straight-six is louder than I’d imagined it would be. Far more aggressive. Its throttle is featherlight, though, and I hamfootedly kick the three Webers awake. My left tympanum goes into spasm. That’s a bazooka of an exhaust. At tickover, it’s as if individual power pulses can be differentiated; superheated smoke rings at supersonic speeds. I inhale. Deeply. And select first.