“Every centimetre,” he asserts. “I did hundreds of testing laps. Every evening after I had finished my work at the school, I used to do two or three laps. For every single corner I had my point of reference: a tree, a house, a wall, a dip down. I knew every corner and how to set the car up for it.”

But Vaccarella is adamant that he was not alone in this: “Other pilots knew it as well as me. From 1961 the race was very professional. Before then, perhaps some of the drivers did not know the track as well, and so were improvising, but after that it was all good, professional pilots: Elford, Siffert, Rodriguez, Kinnunen, Merzario, Moss, Collins. Which is why you had to be flat out, even on the Targa Florio.

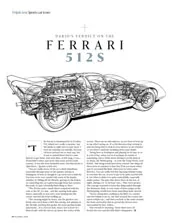

“I don’t know how many thousands of times you had to change gear. It was the most tiring thing in the world; continuous gearchanging and concentration. After two or three laps I was physically exhausted — especially in 1970 when I drove a at 620bhp Ferrari 512S. After one lap in that car I was dead, absolutely finished. I thought it was because I was eight years older than my co-driver, but even [Ignazio] Giunti said, ‘I’m destroyed’.”

Vaccarella on the Targa

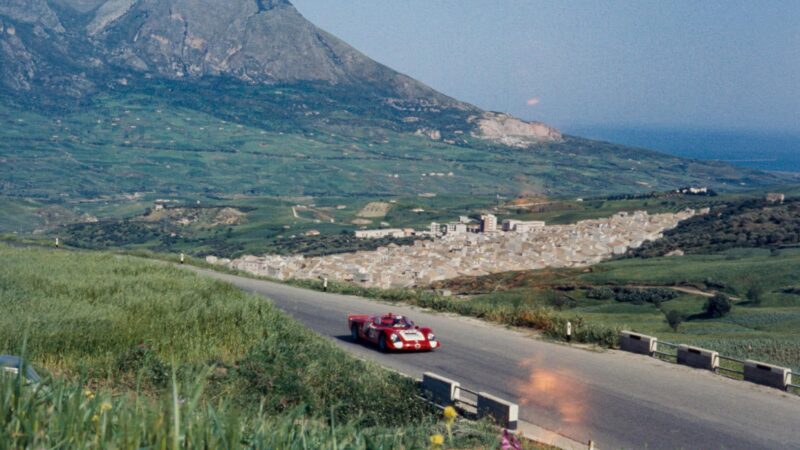

Taking on the ’68 Targa Florio in the Alfa Romeo T33/2

DPPI

1958 Retired — shared a Lancia Aurelia with Enrico Giaccone

1959 10th — co-drove Giuseppe Allotta’s Maserati A6GCS

1960 Retired — shared Lucky Casner’s Maserati Birdcage with Umberto Maglioli. Both led but Nino holed the fuel tank on lap eight.

1961 4th — shared a Scuderia Serenissima-run MaseratiT63 with Maurice Trintingnant Nino was fourth after lap one…

1962 3rd — shared Serenissima’s Porsche 7I8GTR with Jo Bonnier. They might have won but for total brake failure from lap three

1963 DNS — works Ferrari debut that never was: Nino prevented from starting by local police following a road accident

1965 1st — led from start to finish in a works Ferrari 275P2 co-driven by Lorenzo Bandini

1966 Retired — works Ferrari 330P3 was leading comfortably when co-driver Bandini was forced into ditch by a slower car on lap eight

1967 Retired —Vaccarella was easily quickest in practice with a Ferrari 330P4 and held a big lead after lap one, only to crash in Collesano

1968 Retired — co-driver Udo Schutz shunted their Alfa Romeo 33/2 on lap four when lying in second place

1969 Retired — running best non-Porsche, fifth, when the Alfa 33/2 he was sharing with Andrea de Adamich blew up on lap seven

1970 3rd —Vaccarella and Ignazio Giunti manhandled their Ferrari 512S to give Porsche a fright. Led briefly but slow stops cost them dear

1971 1st — Nino and Toine Hezemans couldn’t match Porsche pace early on but, when the leaders punctured, their Alfa 33/3 pounced

1972 Retired — shared an Alfa Romeo 33T13 with Rolf Stommelen and retired on lap four with a blown engine

1973 Retired — co-driver Arturo Merzario led but retired their Ferrari 312PB on lap two after running on a puncture damaged a halfshaft

1975 1 st — won comfortably in an Alfa Romeo T33T1I2 co-driven by Merzario. But non-championship race a shadow of its former self

That race was a microcosm of Vaccarella’s situation: Ferrari sent what they had; Porsche built cars ideally suited to — then specifically for — the Targa. The German marque was the dominant force in the second half of the 1960s, yet Vaccarella only drove for them once on the island. This paucity wasn’t for the want of opportunity, however: “Porsche had a great love for me and they courted me in 1966 and ’67. But my love for Ferrari was even bigger; I preferred their P3 and P4 to the 2-litre Porsches because I preferred cars with lots of power.”