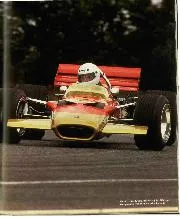

First, it seems appropriate to dispel any illusions that may surround our readers concerning a 3-litre F1 car. Successive designers over the past eighty years have devoted much of their lives to the endless quest for speed and track performance which is the essence of a racing car’s existence. Progressively, F1 cars have become more specialised and further removed from their road counterparts than one could ever have imagined, so if there is anyone who thinks that a 450bhp single-seater projectile, weighing just over 1,300lb and transmitting its power through to the road via enormous 20in wide rear tyres, has anything to do with high speed road motoring then they would be well advised not to try driving one. F1 is very much an area for specialists and my stint round Silverstone served merely to convince me just how excellent a standard of driving is maintained by the people habitually at the back of a grand prix grid, let alone at the front.

Strapped into the cockpit, the Shadow seems absolutely tiny

The first minor problem with the Shadow arose when I slid into its cockpit wearing a pair of soft driving shoes. The Shadow monocoque tapers forwards fairly drastically, being little more than five inches wide at the front of the footwell which accommodates not only throttle, brake and clutch pedal, but also a foot rest to keep the driver’s left foot from inadvertently riding the clutch pedal. Once the front body and cockpit section was secured, I found it impossible to move my feet at all as they seemed firmly wedged between monocoque floor and glassfibre body section. Off came the body section, off came my shoes and I was left, in comfort, to start driving in my socks.

Pedals, gearchange controlling the precise five-speed Hewland gearbox, and steering wheel position, all proved ideal once I’d been strapped into the Shadow cockpit. Ear plugs are an absolute necessity for F1 motoring, but one receives the biggest surprise when one comes to fire up the engine. A quick flick of the switch on the instrument panel to activate the electric fuel pump, on with the ignition switch on the centre of the steering wheel and press the starter button. The Cosworth DFV bursts into life with as much fuss as a 1,600cc Formula Ford and burbles happily over at around 2-3,000rpm without a hint of temperament. The clutch is pleasantly soft in action and, although my elbows flexed the fibreglass cockpit side slightly, the gear-change movement is splendidly simple once you’ve got used to moving little more than your wrist. Strapped securely into the cockpit with the top section screwed down, the Shadow seems absolutely tiny.

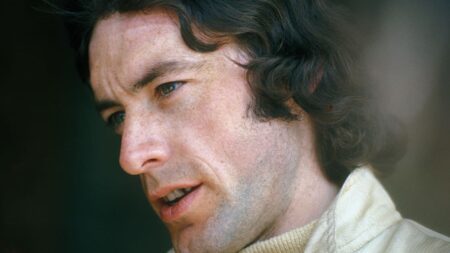

Alan Henry managed to fit into Tony Southgate design – much to his surprise

Grand Prix Photo

On the move, the Cosworth V8 is surprisingly docile and can easily he driven ‘off the cam’ with no juddering, spluttering or misfiring. For the first few laps it became clear that it doesn’t really matter whether you’re in first or fourth gear for between 4,000 and 7,000rpm the DFV offered ample torque for my requirements. In fact it didn’t take long to realise that one could travel round the circuit, apparently quite quickly, without ever getting the engine revving much over 7,000rpm. It is only when the rev counter needle approaches the 8,000rpm mark that the whole complexion of the scenery changes.