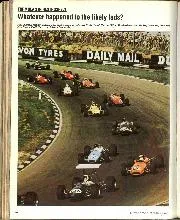

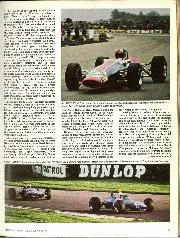

Formula 3 in retrospect

Whatever happened to the likely lads? In the late 1960s any aspiring Formula 1 ace simply had to get into Formula 3 somehow or other. These days we're used to…

THE CAR AS A PERSONALITY

The motor-car nowadays tends to be regarded merely as a means of transport, and those enlightened souls, most of them sports-car owners, who still get a ” kick ” from a smooth-running engine devouring the miles with evident pleasure, rarely put their feelings into print. We must therefore salute the arrival of ” Motor Tramp ” a motor-cum-travel book by John Heywood, as a work which does justice to the joy of motoring as the open-road driver knows it.

The book opens with the author collecting his car from the works and the feeling of pride which every new owner experiences. The make of the car is not mentioned, but the two illustrations make it clear that it was one of the early M.G. Magnas. It covered 20,000 miles in mud and snow and over pave all over Europe without overhaul, and more than justified the first flush of enthusiasm. A cheap holiday abroad was the first objective, and owner and passenger had sundry adventures as they journeyed to Berlin sleeping in the car each night. The author got a position as a film adviser, and his three weeks holiday blossomed out into a stay of six months. His first holiday was in the depth of winter, and he set out alone from Berlin to drive to the Tyrol. All one’s memories of the Monte Carlo Rally revive in reading the log of the journey; for two days the car ploughed along over snow and ice and at last gained the Austro Italian frontier. A slight spar with a

customs official over a tin of English cigarettes quickly led to friendship and together the two set off on a ski-ing expedition in the Italian Tyrol, which was until 1918 Austrian territory.

Here and in a later trip in Austria where Nazi propaganda was disturbing DolIfuss and his colleagues, the author shows himself a keen observer, and gives a clear-cut picture of the feelings of uncertainty and distrust which prevailed in those parts, a state of affairs which anyone living in the settled land of England finds difficult to picture. Journeying farther afield he spent several months in Czechoslovakia. An extraordinarily interesting country this, in which the electric lights and fairly gay life of the capital have made little or no impression in the lives of the peasant classes. Apart from that the population is made up of a number of completely different races, and the author instances a man and wife he met there, one of them Czech and the other Slovak, who could only understand one another when they spoke German. In all these journeys the car was naturally well to the fore, and the amusing way in which the book was written suggests the author as the ideal travelling companion. He is at the same time a critical observer of motoring itself, and we liked his description of the ordinary motorist of our own and other nations. In Berlin he saw ” little cars owned by little men with big cigars in their mouths and no notion of danger in their heads rushing out of right hand lanes (these of course have priority in Germany)— tyres shrieked.” Returning to England and proceeding towards London he saw ” little saloons which rocked and swayed past with no warning from the horn, their tyres splayed out on the corners and their bodies straining away from the light suspension. Their drivers … all seemed in a furious temper.” Finally the Italians ” made themselves a continual

atmosphere of crisis and death. They acted naturally in a crisis because crisis was their natural progression. Every Italian was born a racing driver.”

A ‘final word on the photographs which decorate the book. Instead of being reproduced on shiny ” art,” they are printed direct on the excellent paper used for the text, and as such form an integral part of it, besides gaining from the naturalistic.

point of view. Apart from that the author’s experience of the film studio has stood him in good stead in choosing the ‘• shots ” and the whole forms one of the most enjoyable books we have encountered for a long time.

“Motor Tramp” is published by Jonathan Cape of 30, Bedford Square, London, W.1, and costs eight shillings and sixpence.