Driving the Lotus 49: Grand Prix Crown Jewel

Of all the racing cars made during the 100-year history of Motor Sport, the 49 is the true diamond. Karun Chandhok takes Graham Hill’s chassis R10 out for a few laps at Lotus’s sacred space – Hethel

Jayson Fong

The era that made me fall in love with Formula 1 was the late 1980s and early 1990s. People often ask me about my favourite F1 cars at which point the Williams FW14B, the Ferrari 641 and the McLaren MP4/4 come to mind with the beautiful curves of the Jordan 191 pushing it into that bracket. I guess we’ve all got a ‘first-touchpoint bias’ when answering the question.

However when I take off the rose-tinted glasses and look at the history of the sport more objectively there is no doubt in my mind that the Lotus 49 is the most significant car in F1 history. This firmly puts it on the bucket list of cars to drive for any racing driver who is a true fan of motor racing. I’ve been fortunate to drive an F1 car from every decade of the sport going back to the 1930s, right up until the 2019 hybrid-powered Mercedes that took Lewis Hamilton to the world championship title that year. The list includes 12 world championship-winning cars and this has given me the wonderful opportunity to appreciate the evolution of the sport from the cockpit.

Clive Chapman and his team at Classic Team Lotus kindly let me drive the 49 before at Monza but somehow driving it at its spiritual home at Hethel felt extra special. Sitting in the cockpit is actually remarkably comfortable. I suppose the chassis had to be designed to accommodate Graham Hill who I’m told was reasonably tall. When you first look at the off-centre steering wheel, it seems very odd but actually once you pull away and start driving, it’s not really something you think about. Frankly, I felt grateful for the extra space to change gear.

I remember reading that the ZF gearbox was something of a sticking point between Chapman and Cosworth as they favoured the Hewland option. The gearbox itself may have had some reliability issues back in the day but it was remarkably user-friendly for something built nearly 60 years ago. I found it very straightforward to go up and down the box, with a lovely positive feeling as the lever went through the gate and selected every gear.

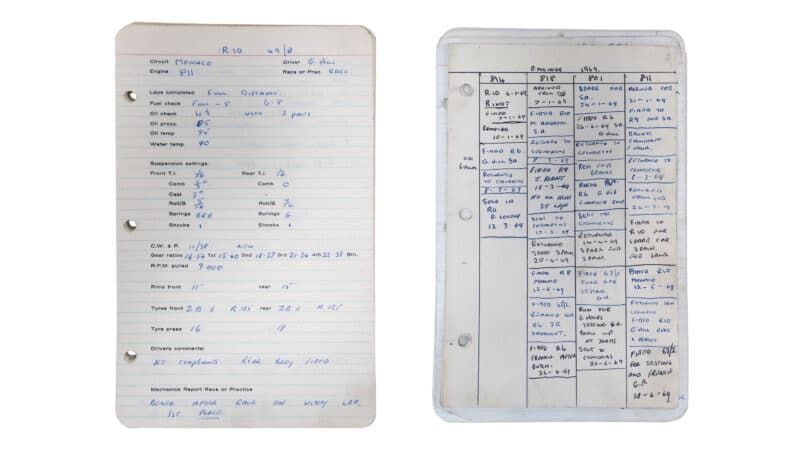

From left: Lotus mechanic’s report for the 1969 Monaco GP; DFV engine information for 1969. Left: note off-set steering wheel

One of the big debates around the Lotus 49 has always been: is it a case of a great engine in a decent car or a great engine in a great car? Certainly people like Jack Brabham believed that other cars and teams would have been even faster and more successful with the DFV engine in 1967. Experts would say that the Honda and Eagle V12s probably had more power although ironically the Ferrari had less. In reality the H16 engine at BRM was probably the first stressed-member engine in F1 but it was the compact size and stiffness of the DFV which allowed its beautiful integration into the Lotus chassis. Chapman and the team were able to build a lightweight car with good torsional stiffness because of the DFV engine and ultimately the whole car succeeded as one.

“It was the size and stiffness of the DFV which allowed its beautiful integration into the chassis”

I absolutely love driving the DFV engine cars and experiencing this earliest iteration gives you an immediate appreciation of why the DFV won 155 grands prix across a 17-year period. Of course it’s powerful but as I said before, there were others that also created the pure grunt. It’s the driveability and linear torque curve which makes it an absolute pleasure. In an era where the cars didn’t have downforce and balancing the rear of the car on the throttle was an art form, having an engine that was predictable in its response must have been a huge advantage.

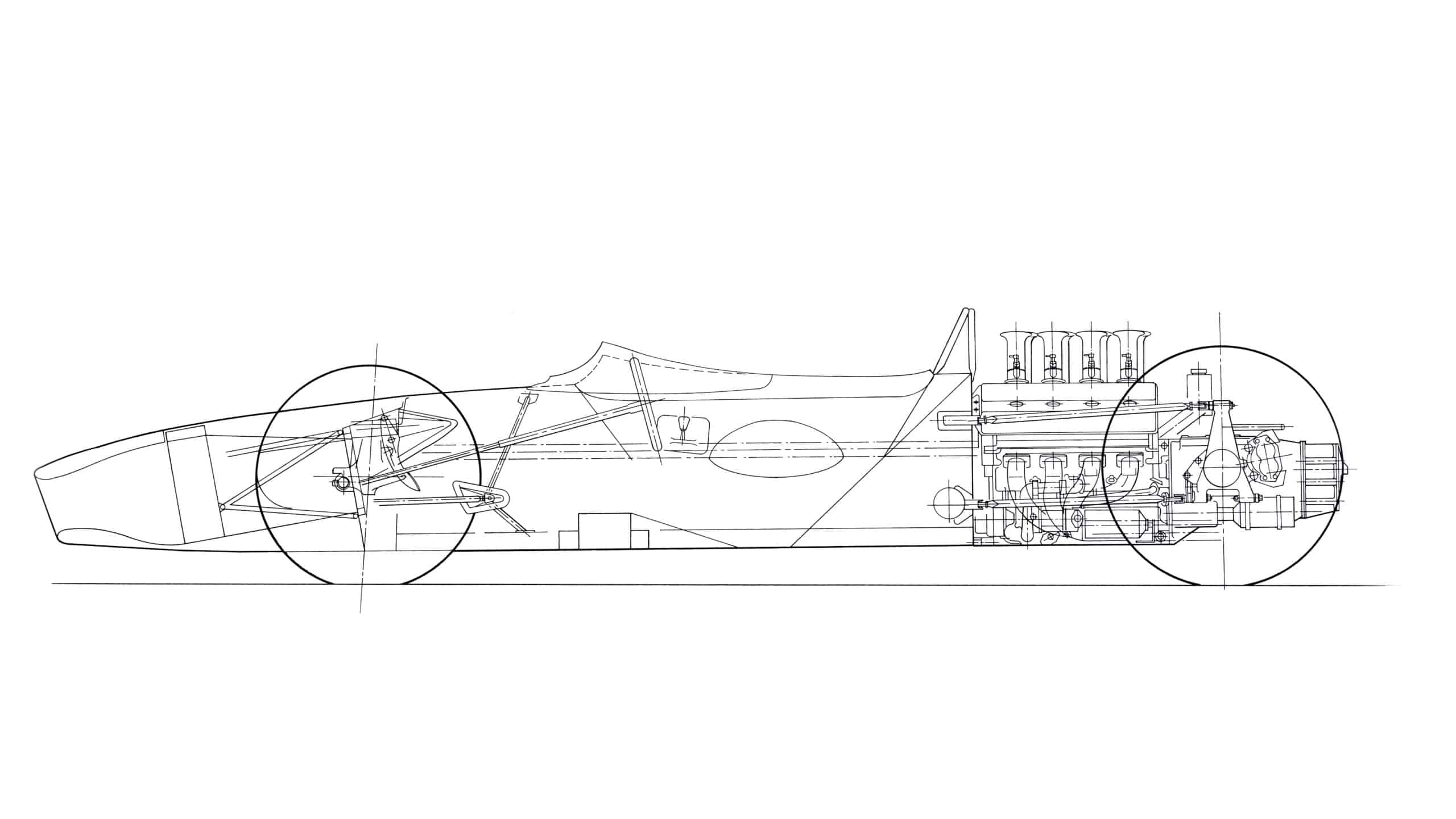

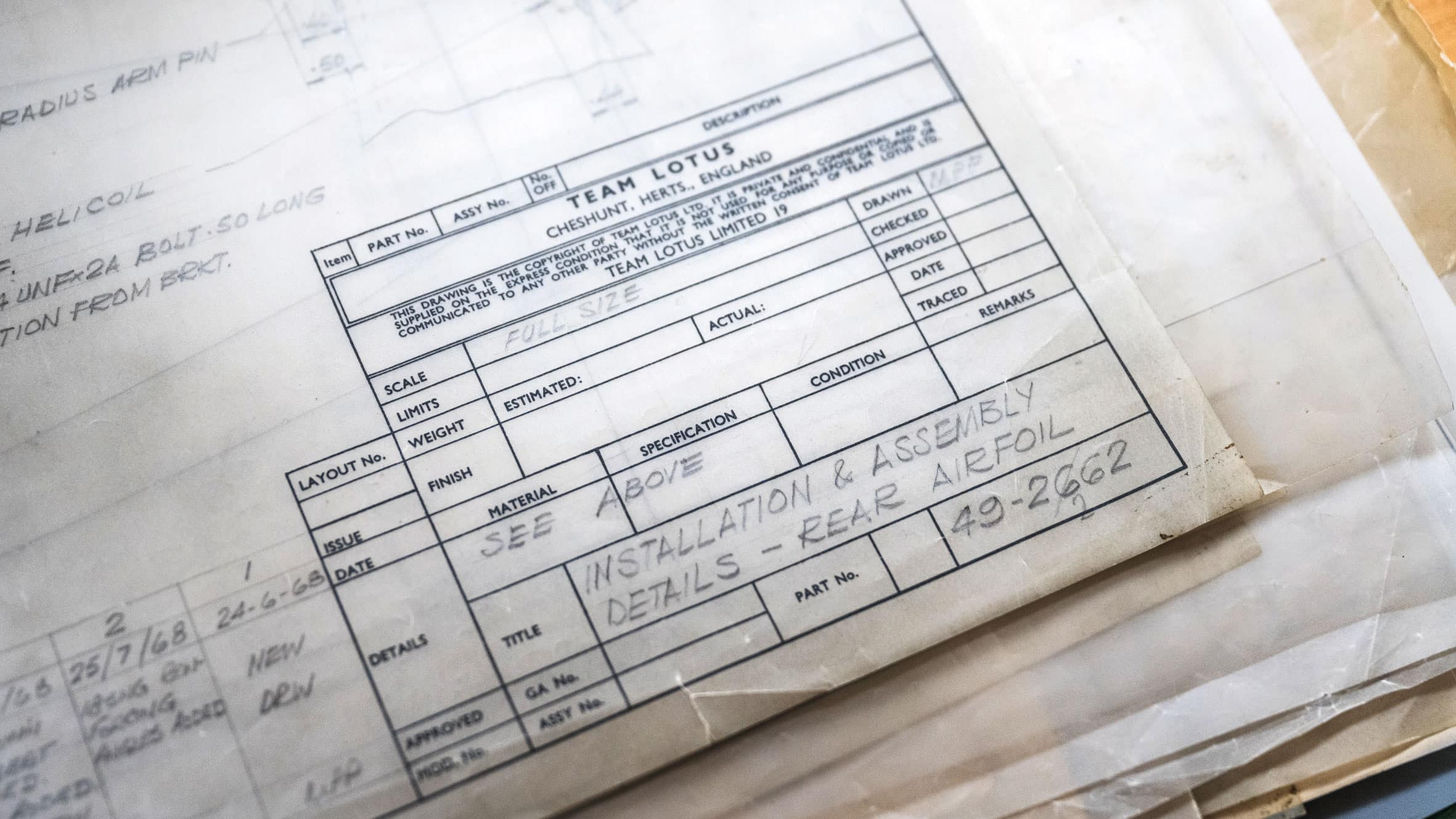

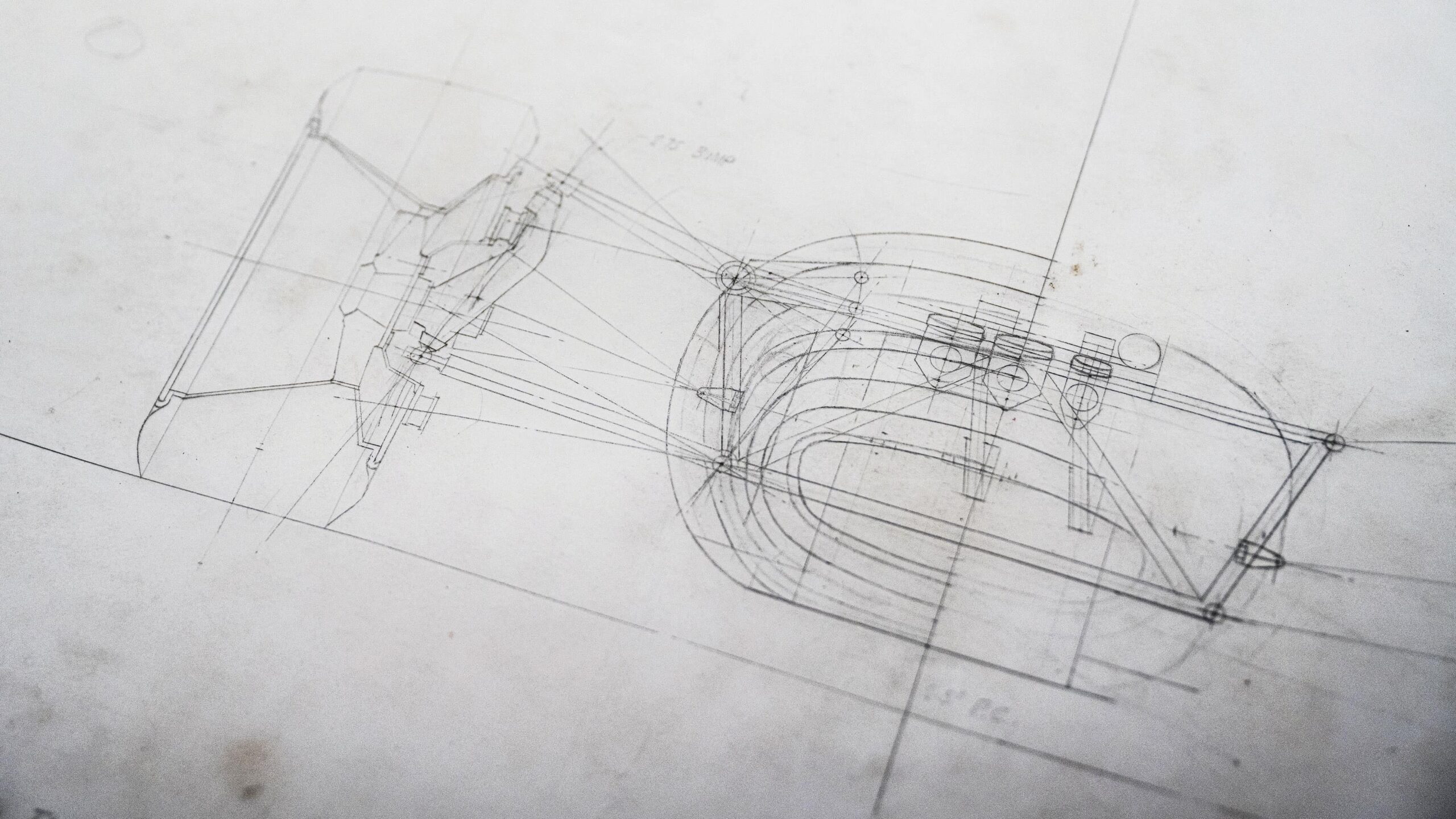

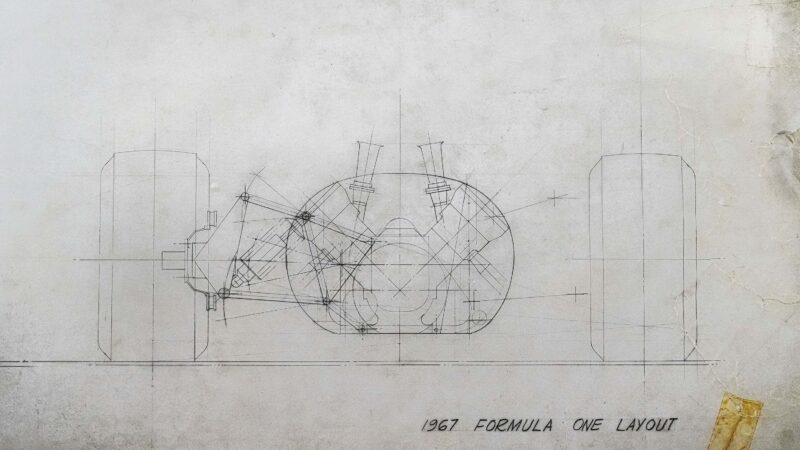

Priceless treasures from the Lotus archive – these full-size drawings of the Lotus 49 are the work of Maurice Phillippe, chief designer of the car

As you start to accelerate from the apex, the amount of power supersedes the amount of grip and the rear of the car starts to step out of line. Having a torque curve without any obvious dips means that you’re able to start using the loud pedal and just control the wheelspin in a way that after a few laps you find yourself using the throttle to rotate the car around. Before long, you start to dream you’re holding the slides like Jimmy Clark – without a fraction of the great man’s actual talent of course. Any mid-corner understeer can be balanced up with your right foot, getting the rear of the car to come around and open up the trajectory to get on the straight quickly. Getting rid of any lateral load and straightening the car is really important as the lack of downforce means that traction is always a challenge.

“The chassis I was driving has won the Monaco Grand Prix twice in Graham Hill’s hands”

The chassis I was driving has a unique history in being the only one that has won the Monaco Grand Prix twice in Hill’s hands and I suspect it still had the gear ratios in for something like Monaco. Before I knew it, I was pulling 9500 in top gear down the back straight! Of course with the lack of wings, there’s much less drag on the car and combined with the weight being down at just over 500kg, the 410hp engine helps you accelerate very quickly.

Unquestionably, a key criteria for success in that era of the sport must have been predictability. With the introduction of the 3-litre engines, the ratio of power to grip firmly tilted towards power in that era. The drivers would have craved a car that was going to be compliant over bumps and undulations and balanced in the corners for them to achieve consistency and be safe.

“As you accelerate from the apex, the amount of power supersedes the amount of grip”

One thing that is clearly noticeable in the Lotus 49 in comparison to the cars from the 1970s, let alone the 1980s, is just how much softer it is. You really feel much more movement in terms of pitch when you get on the brakes and lateral roll as you snake your way through the appropriately named Graham Hill esses.

Following in the footsteps of Graham Hill, Jochen Rindt and Mario Andretti

Jayson Fong

At the end of the straight I did the classic ‘downforce era’ driver thing of jumping on the brakes hard. In a high downforce car you try and maximise the aero performance at peak velocity and attack the brakes to gain the benefit but I quickly realised that with the Lotus, I needed a reset.

“I feel privileged to have driven what is unquestionably the greatest racing car”

Driving these cars was all about smooth applications – give the car a warning that you are about to transfer the weight forward rather than shock it with a hard stab. It’s the same principle with the steering – you have to tease it with a subtle little turn first to get the weight transferred in the right direction before loading it up. You find yourself in this constant dance of hands and feet, manipulating the throttle, brakes and steering wheel to keep the car moving around but always thinking about how to carry momentum through the corners.

A smooth racing style is required with the 49 – no ‘downforce driving’ into the curves

Jayson Fong

This is why the great drivers like Clark and Stewart were able to stand out among their peers – the drivers really drove the cars. Every input they made in this dance was translated to the road without being filtered by any electronics for the power steering, brakes or differential.

The cornering speeds are a long way down from anything we saw once the ground-effects era began a decade later but the cars feel alive and you really have to be comfortable with the constant movement and micro-corrections. But fortunately my time racing historic Can-Am cars as well as E-types and Cobras at Goodwood has been helpful in getting used to this.

Naturally, I left Hethel with a massive smile on my face. As a purist, I loved the opportunity to drive a car where every single movement I made with my hands and feet had a direct effect on the movement of the car. And then there was the wonderfully smooth torque curve and glorious sound of the DFV engine, playing with the throttle to get the rear of the car to come alive at every exit.

As a historian of motor sport, I feel privileged to have driven what is unquestionably the greatest racing car, with the greatest racing engine of the past 100 years.

Lotus 49: race record

World championship GPs: 50

Wins: 12

Podiums: 23

Pole positions: 19

Fastest laps: 14

First race: Dutch GP, Zandvoort, June 4, 1967 1st, Jim Clark

Last race: Spring Trophy, Oulton Park, April 9, 1971 6th, Tony Trimmer

GP wins

1967 Dutch GP, Zandvoort, Jim Clark

1967 British GP, Silverstone, Jim Clark

1967 United States GP, Watkins Glen, Jim Clark

1967 Mexican GP, Mexico City, Jim Clark

1968 South African GP, Kyalami, Jim Clark

1968 Spanish GP, Jarama, Graham Hill

1968 Monaco GP, Monte Carlo, Graham Hill

1968 British GP, Brands Hatch, Jo Siffert

1968 Mexican GP, Mexico City, Graham Hill

1969 Monaco GP, Monte Carlo, Graham Hill

1969 United States GP, Watkins Glen, Jochen Rindt

1970 Monaco GP, Monte Carlo, Jochen Rindt

Non-championship F1 wins

1967 Spanish GP, Jarama, Jim Clark