Mercedes’ F1 bounce back

The team that once utterly dominated Formula 1 has had a torrid two years. Now, finally, it appears to have refound its mojo. But why has it taken so long? Andrew Benson investigates what went wrong

Getty Images

After two painful years, a lot of soul-searching and a fair few blind alleys, Mercedes has finally seen the light at the end of the tunnel in Formula 1. In the end it has all happened quickly. After the Miami Grand Prix, George Russell made a remark that really brought home how far Mercedes had fallen since becoming the most successful team in F1 history and winning eight consecutive constructors’ titles from 2014 to 2021. Russell had finished eighth, two places behind team-mate Lewis Hamilton. At the front of the field, 35sec ahead of Russell and 17sec in front of Hamilton, Lando Norris had just won the race in a McLaren powered by a Mercedes engine.

“It shows what’s possible when you get things right,” Russell said, “but for now we don’t have things right, and we need to make changes quickly. We have to accept that we are the fourth-fastest team at the moment.”

And yet by mid-June, after a series of upgrades to the car over successive races, Russell was on pole position for the Canadian Grand Prix. And while he finished third in the race, both winner Max Verstappen and Norris, who joined him on the podium, felt the Mercedes had been the fastest car.

Two weeks later, Hamilton took third place, again behind Verstappen and Norris, at Spain’s Catalunya track. And Russell – who had briefly led the race after a lightning start from fourth, where he eventually finished – said: “We really feel we are getting a bit of momentum. It’s shifting and it’s with us, and we know what we need to do to make the next big leap with our updates.

“I’m confident we can win races this year now. We have led two races in two weekends after the upgrades. We wouldn’t have expected that at the beginning of the season.” Then came his fortuitous, but significant, victory in Austria. Mercedes’ first win in 33 races.

Mercedes’ technical director James Allison believes that F1 success brought complacency

DPPI

Mercedes-Benz

Mercedes-Benz

How has Mercedes found the path to putting things right? And why has it taken so long? It is, after all, more than two years since the new venturi-floor, ground-effect regulations under which Red Bull has so far dominated F1.

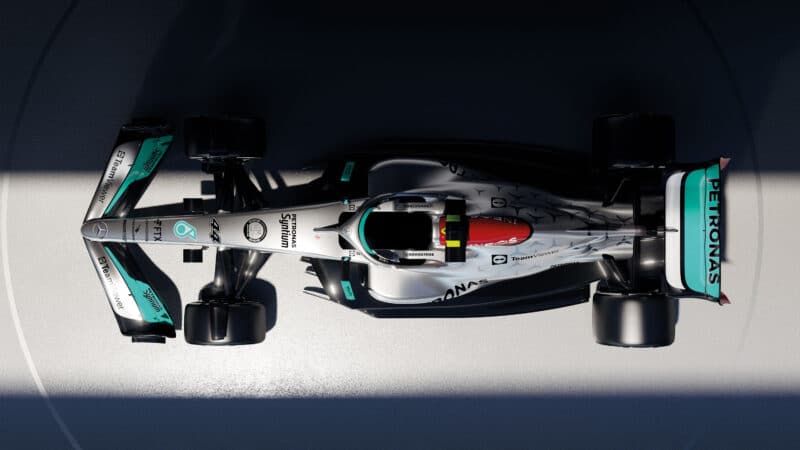

Outside Mercedes – and sometimes within it, too – the focus has been on the observable differences between the Mercedes cars and the Red Bulls. In 2022 and 2023, the designs of the two cars were very different – Red Bull with its heavily undercut sidepods; Mercedes with its so-called zero-sidepod design. This year, the Mercedes outwardly resembles the Red Bull more obviously.

“The most significant thing is not technical but cultural”

F1 engineers will always tell you that the most important parts of the car are the bits you can’t see. Nevertheless, in light of the different achievements of the two cars, it seems valid to ask one overarching question: does the Mercedes team understand how to achieve performance from the latest technical regulations? Put that to Mercedes technical director James Allison and he almost scoffs.

“It’s sort of at one level an utterly facile question and at another level a completely reasonable one,” he says. “So, here’s the level on which it’s facile. Yeah, if you give it more downforce, it will be more competitive. If you make it so that it has cooler rear tyres, that would be helpful. These are exactly the same objectives that every team in the pitlane is aiming for. The question is: how successful are you in achieving those things?”

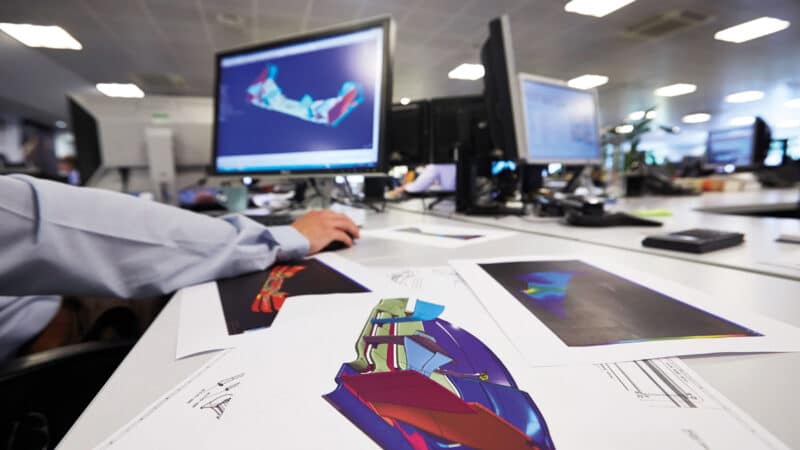

Allison sees the root of Mercedes’ issues at a much more fundamental level.

“The most significant thing is not technical but cultural, really,” he says. “That these rules require different things from an organisation than the old rules did, and eight years of consistent success as a group probably led us to be a bit too confident that the way in which we were working would always get the best out of the resource we were spending.

The W13 suffered with porpoising in 2022

Mercedes-Benz

“We were slow to recognise the fact that the new regulations actually require a different set of skills and a different way of interacting with each other. And when I talk about interacting, I mean the main blocks of the company. So the aerodynamic guys with the vehicle dynamics guys, with the track guys, with the drawing office guys. All of them have always had to interact because you couldn’t do an F1 car without. But the extent to which they need to be in each other’s pockets with these new rules is quite different to the extent to which they had to be in each other’s pockets previously, driven largely by the fact that the cars are so near the ground that the suspension and aerodynamics are closer than blood brothers and need to be designed with the greatest of sympathy to each other.”

Was Hamilton disappointed with his Mercedes contract? Top

Getty Images

Getty Images

Toto Wolff is one of three equal shareholders in Mercedes F1.

DPPI

This is a mirror image of the reason Red Bull’s outgoing chief technical officer Adrian Newey gives when asked why he pursued their particular design philosophy with these rules – for Newey, the integration of suspension and aerodynamic designs was critical to operating the car under the latest rules.

Allison continues: “We carried on for far too long with the more relaxed interactions that had served us brilliantly well under the old set of rules and were slow to recognise the need for us to tighten our act up.”

If this sounds esoteric – how can internal restructuring affect car design? – for Allison it goes to the heart of what went wrong.

Lewis is left behind by Max in the 2021 finale

Getty Images

“The car concept that is so ‘entertainingly’ discussed at every level by everybody is just the outcome of the institutional approach to designing a car,” he says. “And if you are slow to recognise what is weak in the way you are interacting with one another, the targets you are setting, the articulation of what is good and what is bad in terms of which characteristics will make the car go quicker and which ones will hamper it, if your organisation is not set up to deliver a nice trusty path to greater competitiveness then you can talk all day about the geometry of the car; it will matter not one jot.

“Everything about being competitive is about valuing the right things, putting resource onto the right things and then pursuing those right things with vigour. The car just pops out at the end as a consequence of that.”

Miami misery – sixth and eighth for Mercedes

Getty Images

Among the changes inside Mercedes have been the identities of the people at the very top of the technical team. Allison was Mercedes’ technical director from 2017 until mid-2021. In the summer before the latest ground-effect, venturi-underbody rules were introduced, he moved into a broader role as chief technical officer – away from the day-to-day of F1 – while Mike Elliott replaced him as technical director.

Through a difficult 2022, Hamilton, unhappy with the car’s nervous rear end and forward cockpit design, had pleaded with the team to change tack on many fundamental design features of the car. But they ignored him and stuck with the zero-pod concept, only to start 2023 in no better position, and with Hamilton saying the car felt exactly the same, and had the same vices.

Russell was dismayed with the new car’s handling earlier this season.

Getty Images

Early in the season Elliott was replaced by Allison, in what was presented as a job swap at Elliott’s behest to maximise the skills of each man. Few believed the official line. And, within months, Elliott had left the team.

By Monaco of 2023, the zero-pod concept had gone, as Mercedes took as big a step towards a Red Bull-style design as was possible within the constraints of the car’s architecture.

On the thinking behind this move, Allison says: “It was a sort of a priori geometry change so that we didn’t have to die wondering. But arguably that geometry change made us a bit slower that year.”

While this season has seen gradual improvement at Mercedes, there’s much hope for 2026 when the new F1 regulations start

Mercedes-Benz

Allison rejects the idea that altering the technical leadership of the team was a major influence on Mercedes’ problems at the start of this rules era.

But he admits that two and a half years into a new set of regulations is perhaps a little late to have come to the realisation that the team was going about things the wrong way.

“We should be disappointed that it’s taken this length of time to have a sober assessment of [what was wrong] and to then enact the cultural changes to put it right,” he says.

“We are on a trajectory where we are making the car better”

He says that it would be “grossly overconfident” to suggest Mercedes is now definitively in a good place, but adds: “I feel like we have an appropriate level of self-awareness and internal critique happening that is making the key folk in the company realign how they work, reassess what they value, restate what makes lap time emerge and that that is resulting in improvements we see on the track.”

It has been a difficult path to this point. Mercedes believed the 2022 car would produce prodigious amounts of downforce by running close to the ground. But it suffered from porpoising – a phenomenon common in cars with venturi underbodies which sets up a vertical bouncing as the airflow stalls and reattaches. So the 2023 car was designed to have an aerodynamic optimum at a higher ride-height – only for the team to realise that running as close to the ground as possible was important.

Andrea Kimi Antonelli will likely partner George Russell in 2025

Getty Images

Team principal Wolff says: “We have been zig-zagging as to where we thought we need to have the performance, and one thing you cannot buy in F1 is time. Once you have got it wrong, you’re on the back foot. We understand much more what is needed to get the car in a better space. It has been a painful learning curve and it is still not satisfactory, but the situation is more encouraging. We are on a trajectory where we are making the car better. I feel more confident now.”

Wolff admits that he is “not particularly proud” of the path Mercedes has trod recently.

“We could have done things better and differently and spotted things earlier and optimised within the organisation, and we didn’t,” he says.

A new concept was introduced for 2024, but still Mercedes found itself in trouble. Early this season, Mercedes realised it could balance the car in slow-speed corners, but only at the expense of high-speed oversteer; or in high-speed corners, at the expense of slow-speed understeer. But new bodywork in Miami, a new floor in Imola and a new front wing in Monaco made it possible to eliminate this flaw. Over that period, the car has improved. It has gone from 0.688sec on average off pole position in the first five races to 0.266sec off in the second five. It has also reduced the gap to Ferrari from 0.322sec to 0.049sec.

Some have looked at Mercedes’ travails over the last two years and formed a theory. This, they say, is all proof that the team’s success was down to the foundations laid by Ross Brawn before the era of hybrid engines. Wolff, the theory goes, has simply ridden Brawn’s coat-tails, and now, under a new regulation set, is being found out.

But there’s a problem with that theory. For a start, crediting Brawn alone with the successes of the initial hybrid era ignores the critical contributions of technical leaders Bob Bell and Aldo Costa on the chassis side and former engine chief Andy Cowell.

But beyond that, the theory does not even make sense. Mercedes’ success has already continued through one massive regulation change – to wider cars in 2017 – and several changes in the technical leadership team, including Allison arriving as technical director in 2017, long after Brawn departed at the end of 2013. It took the ground-effect rules to really upset the apple cart.

The current F2 driver will be 18 years old.

DPPI

It is, though, valid to question Wolff’s role in all of this, After all, as leader, the buck stops with him. But his position is not equivalent to that of a football manager who could be sacked. He is not only a shareholder, but he owns a third of the company, along with Mercedes and Sir Jim Ratcliffe’s Ineos.

Wolff says: “As a co-owner of this business, I need to make sure my contribution is positive and creative. I would be the first one to say if somebody has a better idea, tell me, because I am interested to turn this team around as quickly as possible.

“I look at myself in the mirror every single day about everything I do. Do I believe I should ask the manager a question? It is a fair question but it’s not what I feel at the moment.”

So where do the other shareholders stand? Squarely behind Wolff, it seems. Mercedes chief executive Ola Källenius, in reducing the company’s holding with the Ineos buy-in, has crystallised the asset value of the F1 team, demonstrating to the Daimler board that it has a monetary value as well as being its best branding platform. Mercedes’ commitment to F1 is open-ended.

For Ineos, it has already been a very successful investment – the valuation of its stake is estimated to have almost tripled since it bought it in 2020.

One big change is coming, though. Over the winter of 2023-24, Hamilton signed to join Ferrari in 2025, making this the final season for the most successful team-driver combination in F1 history.

Why did Hamilton change his mind just months after committing to a new contract with Mercedes in the summer of 2023?

Partly, it was because of the way those negotiations over a new contract had gone. Mercedes had wanted to give Hamilton only a one-year deal for 2024, because it was looking to the future and planning for the arrival of its Italian protégé Andrea Kimi Antonelli, while Hamilton was hoping for a longer commitment.

Wolff was not necessarily planning to fast-track Antonelli in as a replacement for Hamilton in 2025, after just one season of Formula 2. But he was trying to give himself the flexibility to manoeuvre, a position rooted in the way Mercedes lost out on Max Verstappen back in 2014.

At the time, Verstappen and his management team – his father Jos and Raymond Vermeulen – were choosing between joining Mercedes or Red Bull. Mercedes already had Hamilton and Nico Rosberg under contract, and could only offer him a role as reserve, and a seat in Formula 2. Red Bull, by contrast, could give him a drive in F1 straight away, and he took it.

Wolff decided he did not want to lose out on the ‘next big thing’ a second time. In the end, Mercedes and Hamilton compromised. The deal they struck last summer was what is known as a ‘one-plus-one’ – a one-year deal with an option to continue for a second.

Hamilton, his confidence in Mercedes already knocked by their difficulties with the racing car, had been less than impressed by the team’s apparent lack of commitment to him personally. And, like almost every other driver, had always been interested in the idea of driving for Ferrari.

Wolff missed the opportunity to sign Max in 2014

Ferrari had ended the 2023 season in a stronger position than Mercedes, just missing out on beating them to second in the constructors’ championship after a late surge. And when they came in with a deal that not only offered him a longer commitment, but also more money – a reputed salary of $60m (£47m) – Hamilton went for it.

Wolff, for his part, felt let down – he and Hamilton had always said they would be transparent with each other. Yet there was no heads-up, and now Mercedes found itself in an awkward situation when it came to drivers for 2025, with pretty much all the top names under long-term contract, and its room for manoeuvre reduced.

But then the landscape of Formula 1 changed at the start of this season. A female Red Bull employee accused team principal Christian Horner of sexual harassment and coercive, controlling behaviour. It was headline news throughout the world.

Horner has always denied these allegations. With the backing of the majority shareholder, the Thai businessman Chalerm Yoovidhya, he survived the initial storm of revelation, an attempt by Red Bull GmbH in Austria to oust him, and an initial internal investigation into his behaviour, after which the board – led by Yoovidhya – dismissed the complaint.

At the sodden Canadian GP, Mercedes took its first podium of ’24 courtesy of Russell – and there was a second consecutive fastest lap for Hamilton

The complainant has appealed and Red Bull was in the midst of a second internal investigation, led by a different lawyer, as this article was being written. Other legal developments are likely.

Internally, Red Bull has been shaken to the core. Jos Verstappen said back in Bahrain that the team risked being torn apart if Horner remained in his position. Over the course of the first few races, Max was repeatedly asked whether Horner had his full backing, and only ever gave equivocal answers, talking about his wish for people to focus on the racing, and his desire to keep the senior team together.

Meanwhile, the revelations laid bare an internal power struggle at Red Bull – between Horner and the motor sport adviser Helmut Marko, and between Thailand and Austria. There was an attempt to oust Marko, which was when Verstappen made his feelings clear – if Marko goes, so do I, he told Red Bull bosses. Marko’s position was newly secured.

Wolff saw his chance. He is a long-time friend of Jos Verstappen and he realised that, with the Verstappens unsettled by Horner’s behaviour, and Red Bull doing nothing about it, he might be able to tempt Max away.

Verstappen is contracted to Red Bull until the end of 2028. But he has a mechanism by which he can leave whenever he wants. If Marko leaves, he can, too. And, privately, the Verstappens and Marko have come to an agreement – whatever Max wants, Marko will help him get it. So if Verstappen decides to leave, Marko will resign so he is free to do so. The only question remaining is whether that is what Verstappen will decide to do.

“This is no longer the Mercedes that swept all before it for so long”

It seems unlikely to happen this year. Verstappen is said to want to stay, with the aim of securing a fifth world title in 2025, to add to the fourth that already seems inevitable this year. Mercedes looks likely to head into next year with a driver line-up of Russell and Antonelli, who is busy building his F1 experience in tests with recent Mercedes cars.

But for 2026, getting Verstappen is a very real possibility. No one knows what the competitive picture will be when the new rules are introduced. So there is less reason to be put off by where Mercedes are right now – and if they continue their progress to the front, even less again.

And any concerns that Red Bull will steal a march at the start of the new chassis rules period – as it did in 2009 and 2022 – are reduced by the departure of Newey, the first major fall-out of the Horner controversy. Newey’s discomfort at the Horner situation and its consequences was one of the main reasons why he quit – and negotiated an early end to his contract that frees him to work for another team from early 2025.

On top of that, the Verstappens are said to believe that Red Bull’s development programme for the 2026 power units, which will be the first engine produced by the newly established Red Bull Powertrains business, is behind that of Mercedes.

While they wait to see what Verstappen chooses to do, Mercedes is focusing on getting its performance back to a respectable competitive level. And while it waits for the aerodynamic development programme to take effect, Mercedes has had to accept that its reality has shifted.

This is no longer the Mercedes team that swept all before it for so long, with all the cogs perfectly meshed and working in reciprocating harmony. A re-imagination of how it works has been required. Soon, the driver around which that domination was built will also be moving on.

As Wolff puts it: “We are in the process of reinventing ourselves.”

Andrew Benson is the BBC’s Formula 1 correspondent. @andrewbensonf1