Ferrari writes Le Mans history again in 2023

This year’s sell-out Le Mans 24 Hours easily lived up to the race’s storied past. Richard Williams, author of a new book on the French classic, looks at how Ferrari delivered the perfect 100th birthday present

Calado, Pier Guidi and Giovinazzi made history with overall win on Le Mans return

By the time spectators at the next Le Mans 24 Hours retreat from the noise and dust of the race to browse among the exhibits in the museum of the Circuit de la Sarthe, a tiny red car will have taken its place on a miniature podium, mounted ahead of replicas of the other 61 starters in the centenary race. The Ferrari 499P was the car that gave the organisers exactly what they wanted for their 100th birthday: a headline-making outcome that, by ending one historic period of dominance and restoring a famous name to the top of the results, justified the creation of an entire new category at the summit of endurance racing, with Le Mans as its centrepiece.

“The Ferrari 499P gave the organisers what they wanted”

Amid room after room packed with wonders, a hall in the museum is furnished with display cabinets containing 1:43-scale models – Dinky Toy size – of every car to have competed in the 24 Hours since 1923, all precisely detailed and immaculately finished. The enthusiast can happily spend a long time in that room, tracing the evolution not just of one of the world’s most celebrated motor races but of the sport itself and the industry it represents. Had the founders of the 24 Hours been able to see into the future, this is surely what they would have wanted.

The making of history: the twin Ferrari 499Ps lead the field away for the start of Le Mans’ centenary race

Getty Images

The broad vision dreamed up by three men over cups of coffee at the 1922 Salon de l’Automobile in Paris was of an event that would not just promote but improve the motor car and its environment, including the quality of the roads on which it ran. The trio whose interests coincided in Paris’s Grand Palais that day included Émile Coquille, the French representative of Rudge Whitworth, keen on sponsoring an event that would highlight the quick-change properties of his firm’s new wire-spoked wheels. Charles Faroux, a prominent journalist and sometime driver, introduced Coquille to Georges Durand, the secretary of the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, in the belief that their ambitions might coincide. When Faroux put forward the notion of an eight-hour event, with four hours in daylight and four in darkness, Durand went further: why not race once around the clock?

Durand had begun his working life in Le Mans at the municipal department of bridges and roads. In 1923, most of France’s highways – like the section of the N158 from Le Mans to Tours which would eventually become the Mulsanne straight – were roughly surfaced. A collateral benefit of the new race would be the use of a section of public road as a laboratory. In the preparations for the inaugural 24 Hours, the 10.72-mile circuit was resurfaced with a mix of gravel, earth and tar, sealed with calcium chloride – intended to reduce dust, but also prone to stinging the drivers’ eyes and quickly abandoned, eventually in favour of asphalt.

An estimated 325,000 fans made it a sell-out event.

1923’s winning Chenard et Walcker

Getty Images

The museum model room

The start in 1923

Alamy

Three years earlier the circuit had been used for the French Grand Prix, won by American Jimmy Murphy in his Duesenberg, a pure open-wheeled racing machine. The 24 Hours, however, would be contested by road cars equipped with lights, self-starters, mudguards and hoods, all of which had to work properly throughout and would – like the replenishment of fuel, oil and water – be checked constantly by commissaires wielding an intimidatingly thorough rulebook. Thus did Durand and his colleagues ensure that, by attracting manufacturers keen to demonstrate to the public not just the performance but the reliability of their latest offerings, their race would always have a credible raison d’être.

“How much of a rigged outcome was this, and how much simply what is accepted in horse racing?”

Their success could be judged by the amount of newspaper and magazine advertising taken by successful firms, from the full page taken in La Vie Automobile by the Chenard et Walcker company, then one of France’s 10 biggest car manufacturers, whose entries finished first and second in the inaugural event, to the 28 pages of ads in The Autocar 20 years later for the makers of various components of the winning Jaguar and for the Coventry company’s many dealerships around the UK.

Thirty cars out of 33 had finished the 1923 race, largely run in horrible conditions that discouraged excessive speed. The first retirement was a little SCAP which, as if to illustrate the ACO’s emphasis on the need for reliable electrical components, left the track when its lights failed at midnight. The following year, when the race was moved from May to June and a Bentley recorded the first of the firm’s five victories amid high temperatures, only 14 cars finished out of 41. The fight was on for a winning balance between speed and reliability.

It rained on occasion, but much of Le Mans week was blessed with wonderful weather. Here the NASCAR Chevrolet Camaro thunders between the trees

Getty Images

Ferrari’s first win in 1949

Getty Images

NASCAR’s return in 2023

Getty Images

Peugeot’s #94 9X8 led on two occasions during the night, only for Gustavo Menezes to crash heavily at the first chicane while out front in the 12th hour

Getty Images

That fight threw up figures whose names became inextricably linked with the race. Woolf Barnato, king of the Bentley Boys, saved the firm from bankruptcy and became the first driver to win the race three times. Luigi Chinetti, another three-time winning driver, introduced Ferrari to Le Mans at the first post-war edition. Briggs Cunningham disembarked from a transatlantic liner each year like a Hollywood star arriving at Cannes. The brilliant aerodynamicist Charles Deutsch penned futuristic bodywork for his little Panhard-engined DB and CD machines. Pierre Levegh came within an hour of winning the race single-handed before, three years later, finding himself at the centre of the greatest disaster in the sport’s history. Jacky Ickx’s regrets over his stalled F1 career vanished in the glow of six wins in the 24 Hours. Jean Rondeau, a son of Le Mans, drove a car bearing his own name to victory in 1980. Norbert Singer and Wolfgang Ulrich supervised the long years of Porsche and Audi dominance, during which Tom Kristensen, with nine wins, supplanted Ickx as ‘Monsieur Le Mans’.

“Roger Penske looked thunderously disenchanted”

Now, a century on from its invention, the modern 8.46-mile circuit boasts a surface as smooth as a billiard table. The cherished tradition of the Le Mans start and the Maison Blanche complex, where so many hopes came to a sticky end, had to go in the name of safety, while the majestic 3.5-mile Mulsanne straight was trisected by a pair of chicanes. Drivers are no longer required to carry out all necessary mid-race repairs themselves or dig themselves out of sandbanks. No one is now allowed to try racing the whole 24 hours single-handed.

The lustre of the race, however, remains magically undimmed, the product not least of the organisers’ early success in creating the atmosphere of a giant fête. Already in 1924 the official poster showed flappers in summer frocks and young sports in black tie dancing under the moon, the stars and a firework display, while a racing car thundered past the grandstand. Which was the show, and which the sideshow?

Cadillac secured its best-ever Le Mans finish in third and fourth, despite this moment for Scott Dixon

Getty Images

Porsche endured a disappointing Le Mans return, as the 963 couldn’t match the rampant Ferraris, Toyotas and Cadillacs

Getty Images

The days of digging yourself out are long gone

Getty Images

Toyota’s hydrogen future?

But that has never truly been in doubt. The cars are the real spectacle, and it is to the ACO’s credit that their attention has always been focused on the need to stay abreast of changes not only in technology but in public attitudes. After the Arab-Israeli war of 1973, when the price of petrol shot up, attention turned to devising ways of making racing engines more economical. In the 21st century the use of hybrid power has been encouraged and there are plans for a hydrogen-fuelled class by 2030, already given publicity in display laps by the Mission H24 prototype, constructed in the circuit’s Technoparc. The ACO’s belief in ‘green’ hydrogen, made using carbon-free methods, seems to be supported by the unveiling at this year’s race of a Toyota concept car and a joint project on the way from Ligier and Bosch.

To sustain the weight of the race’s history and carry it into the future, charisma intact, while controlling costs and speeds, requires ingenuity as well as vision. In 1949, facing a grid full of dusted-off pre-war machinery, the organisers sanctioned the presence of prototypes for the first time. In the early 1990s, when the combined forces of Jean-Marie Balestre, Bernie Ecclestone and Max Mosley appeared to be succeeding in their mission of cutting Le Mans down to size, the ACO’s then-president, Michel Cosson, defied the governing body by creating new classes, exploiting alliances in the US to fill the grid and restore the kind of allure that would refill the grandstands, too. At the start of the present decade, reacting to the decline of the LMP1 class, Cosson’s successor, Pierre Fillon, also reached out across the Atlantic when it came to creating the two classes, LMH (Toyota, Ferrari, Peugeot, Glickenhaus and the so-called Vanwall) and LMDh (Porsche and Cadillac) that were merged as Hypercars to compete for the overall victory this year.

In order to create an equal contest between the categories, differentiated mainly by their use of bespoke (LMH) and off-the-shelf chassis and hybrid systems (LMDh), the organisers used the Balance of Performance regulations to the full – and perhaps even beyond, given their late decision to impose 37kg of extra weight on the Toyotas, which were going for their sixth win in a row, with an extra 24kg for the Ferraris, 11kg for the Cadillacs, 3kg for the Porsches and nothing for the Peugeots. Toyota’s president, Akio Toyoda, was miffed by a measure that cost his cars more than a second a lap and a place at the front of the grid, occupied by the Ferraris.

Jean Rondeau finally achieves his dream of winning in his own car in 1980

Getty Images

Safety car tweaks weren’t popular

Getty Images

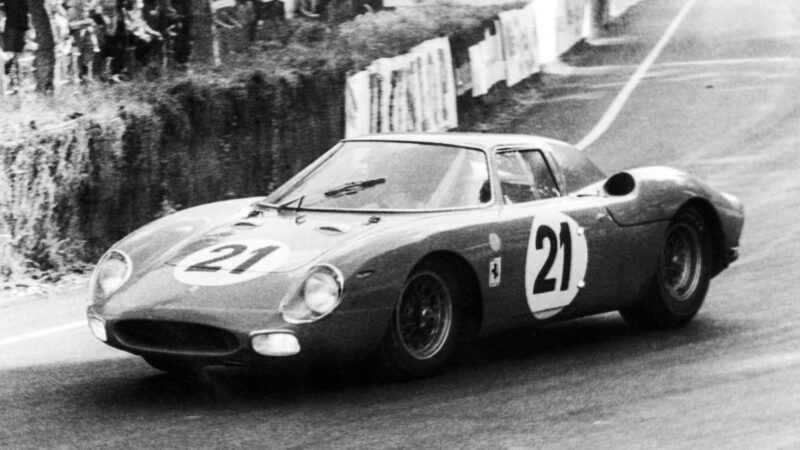

The NART 250LM on its way to Ferrari’s last win in 1965

Getty Images

Menezes pits with heavy damage.

Getty Images

Given that the 499P driven of Alessandro Pier Guidi, Antonio Giovinazzi and James Calado beat the Toyota GR010 of Brendon Hartley, Sébastien Buemi and Ryo Hirakawa by less than half a lap at the end, and that only Hirakawa’s excusion into the barrier at Arnage with under two hours to go may have prevented a reverse of the outcome, the handicappers might well have patted themselves on the back. Ferrari’s 10th victory, the first since 1965, made a great story. There was also the sight, amid the chaos caused by evening rainstorms, of the race being led at various stages by a Cadillac, a Peugeot and a Porsche. Less enamoured would have been Roger Penske, frequently caught by the TV cameras looking thunderously disenchanted as his three factory-supported Porsche 963s ended up with nothing more than limping finishes in 16th and 22nd places and a mid-race DNF. Perhaps Jim Glickenhaus also felt poorly rewarded for his early support of the Hypercar class when his two 007s, beautifully finished in pale blue with the stripes of the French Tricolour, finished sixth and seventh. As for Peugeot, it can only hope a year’s experience with the wingless 9X8 will give it an edge over next year’s Hypercar arrivals: Alpine, BMW, Lamborghini and maybe Isotta Fraschini.

How much of a rigged outcome was this, and how much simply the sort of thing long accepted in horse racing? It probably bothered the sell-out crowd of 325,000 less than the new safety-car protocols that temporarily deadened the race once heavy rain fell on parts of the circuit in the third hour. There will be many hoping never to hear Eduardo Freitas, the race director, utter the phrases “wave-by”, “drop-back” and “pass-around” again, or to see the integrity of a historic race threatened by practices borrowed from Daytona and Sebring.

But all that seemed long in the past by the time Pier Guidi took the chequered flag, his Ferrari having survived a late scare when it refused to restart at its last pit stop, requiring an emergency reboot and giving Toyota a brief glimpse of that sixth victory. But the Italian car with Italian and British drivers got home safely, just as Chinetti and his British co-driver, Lord Selsdon, had done to secure that first victory for the prancing horse in 1949. History may not exactly repeat itself, but sometimes it rhymes.

The winning Ferrari trio

DPPI