Why Isle of Man TT is road racing’s great survivor

The Isle of Man TT is a celebration of road racing that continues to divide opinion. But at its heart it is an unforgiving throwback to the birth of British motor sport and, as TT winner Mat Oxley argues, a glorious anachronism that must be preserved

The Isle of Man is where British motor sport began: the first car races took place on the small island in the Irish Sea in 1904, the first motorcycle races the following year. The car Tourist Trophy (for road vehicles) lasted on the island until 1922. One hundred and one years later, against all odds, the motorcycle TT is still going strong, a giant anachronism and the last-surviving link to the genesis of racing with wheels and engines.

The TT is hideously dangerous. The 37.75-mile Mountain course – which consists entirely of narrow, wildly twisting B and C roads – claims the lives of several riders most years, but still attracts those who are happy to accept the challenge and take the risks.

“It’s an adrenaline rush like no other – the high stays for days, not hours,” says current lap-record holder Peter Hickman, who won four races at this year’s event. “The TT is pretty raw. It’s how motor sport should be – it has risk, speed, skill, accuracy, it’s got everything.”

The fastest race at the inaugural motorcycle TT of 1907 was won by Londoner Charlie Collier on a Matchless at an average speed of 38.21mph. In June, Hickman set a new lap record, at a mind-boggling 136.358mph.

That first TT took place three years after the elimination trials for the 1904 Gordon Bennett Cup car race, staged in Germany. But why the Isle of Man? Because racing on the British mainland had been banned by very low speed limits – encouraged by the powerful railway lobby – while the island (and Ireland) had its own legislature, which allowed road closures for racing.

The incentive for the creation of the motorcycle TT was a series of scandals during the first international races staged in Europe.

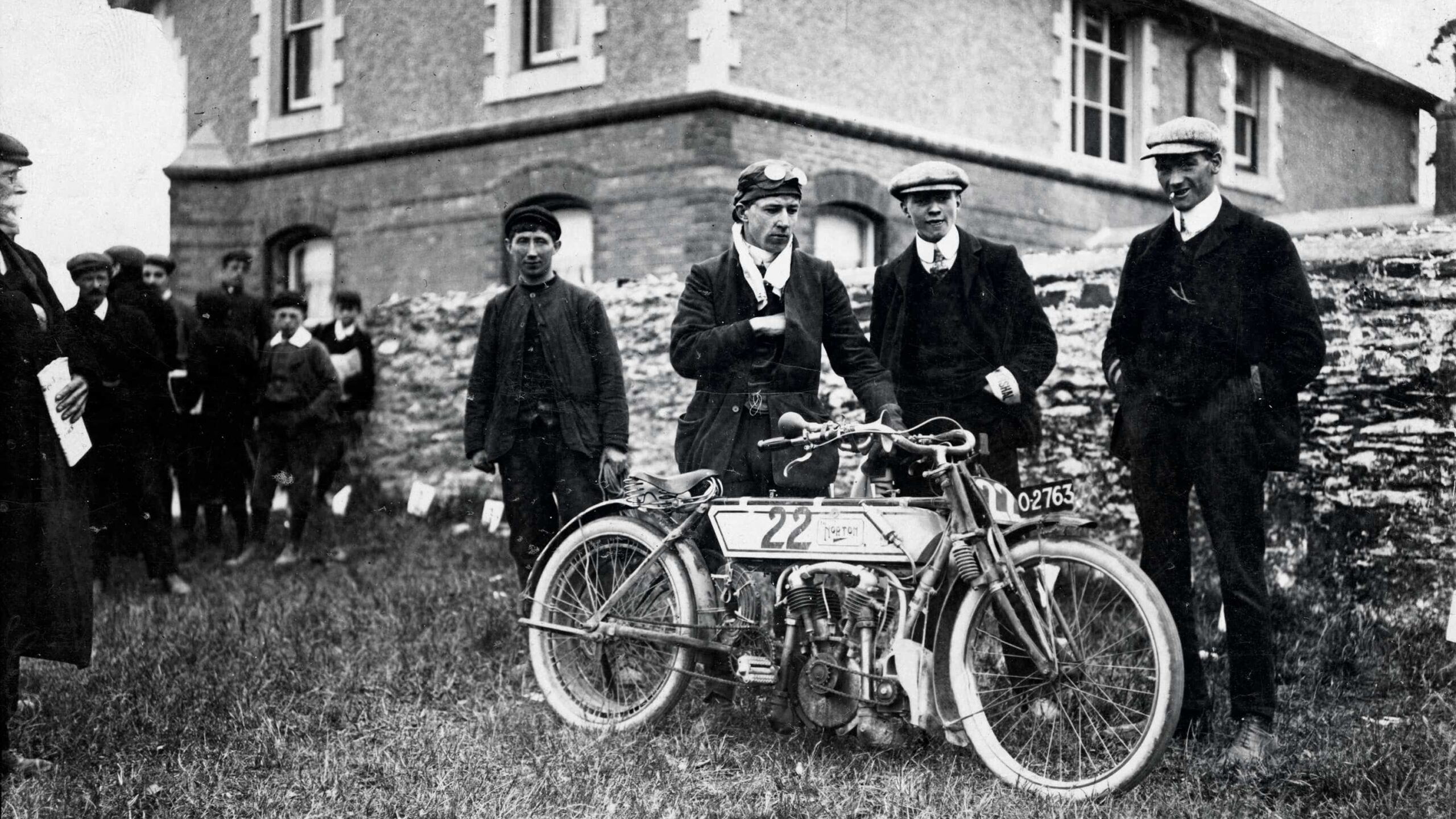

Rem Fowler with his 5bhp Peugeot-powered Norton after the first TT win in 1907. Here

Getty Images

Sidecars also tackle the Mountain

Dean Harrison gets some air

IOMTTraces.com

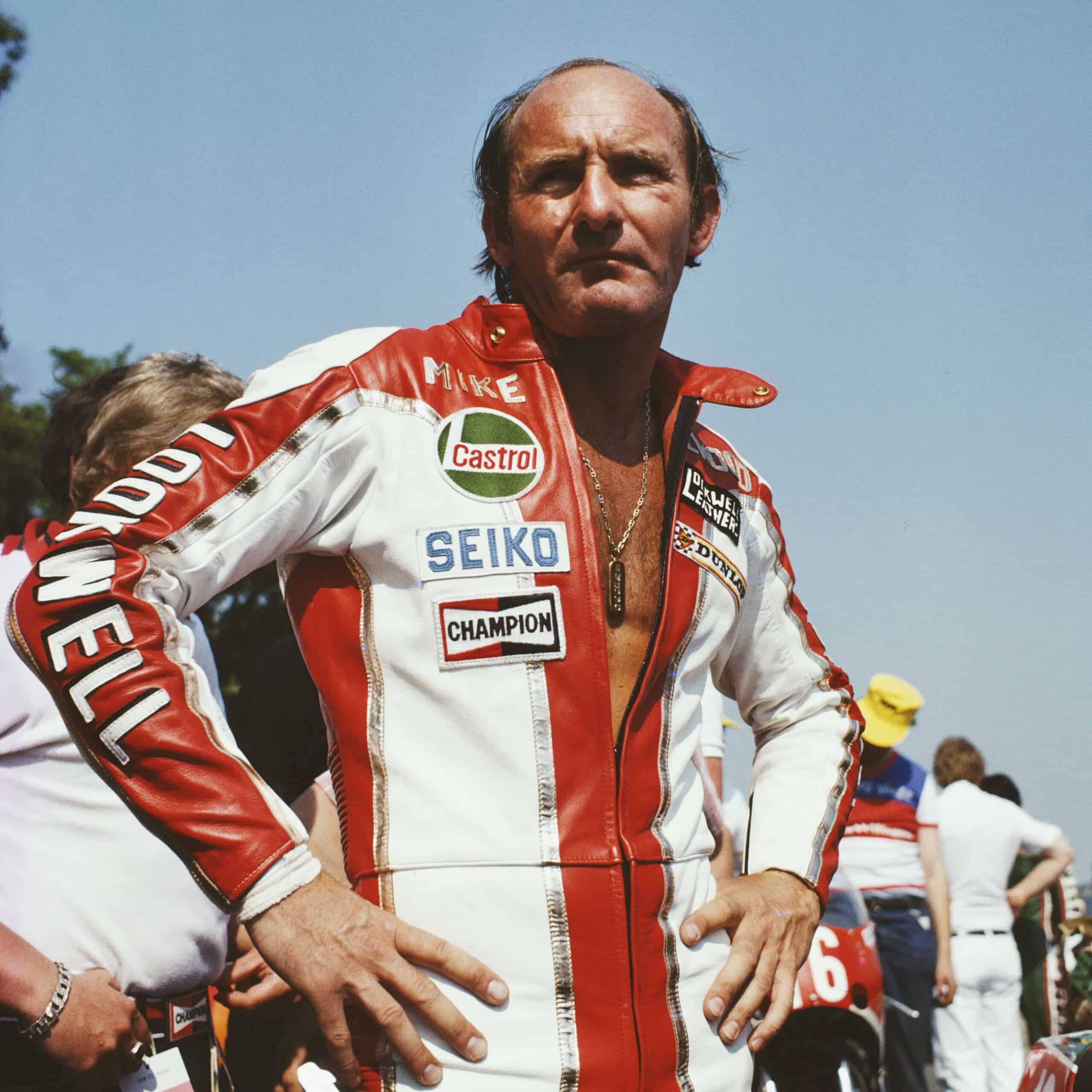

Dressed like a stuntman, to act like one: Mike Hailwood ahead of the 1978 TT

Getty Images

The first Coupe Internationale took place in 1904 around a 33-mile street course, 40 miles southwest of Paris. The event was contested by teams from Austria, Britain, Denmark, France and Germany. The winner was local Leon Demester, who had been runner-up in the notorious 1903 Paris-to-Madrid race, which caused 14 fatalities among racers, spectators and bystanders before it was stopped at Bordeaux. However, a reporter from Britain’s The Motor Cycle publication suspected Demester’s Coupe Internationale victory might not have been deserved.

“Nails strewn across one half of the road, leaving the other half clear… thus proving that this dastardly and unsportsmanlike act was carried out with the intention of rendering certain machines unrideable, while others might avoid them,” he wrote. “And the French team had a complete system whereby their riders could obtain spares from motorcycles laden with necessaries that toured the course in the opposite direction.”

“Every lap is an adventure, and the high is almost spiritual”

Such dastardly deeds were repeated in the 1906 Coupe Internationale, staged in the Austro-Hungarian empire, where the Austrian Puch factory reigned supreme, touring the course in sidecars laden with spares to fix their own bikes. On the train home, disgruntled British team members decided they’d never get to win an international event unless they hosted their own, so they staged two races on the Isle of Man the very next year.

The only reason the event continues is because the island’s parliament allows it, while most other motorcycle races on public roads in other parts of the world have been abandoned for safety reasons.

The event suffered its first casualty in 1911, when the Mountain course was introduced. Since then a further 266 competitors have lost their lives in the TT and lower-level Manx grand prix. Last year alone the TT’s fortnight of practice and racing claimed six lives, from a total of around 90 competitors. Therefore no one goes racing on the island without fully understanding what they are letting themselves in for.

That’s the downside. But, of course, there’s an upside, otherwise the TT wouldn’t happen, would it? There is literally nothing else like riding the course: around 250 corners per lap, most of them taken at over 150mph as the island’s country roads meander their way south from the start-line in Douglas, then looping west and northwards before heading back to Douglas.

Joey Dunlop

Getty Images

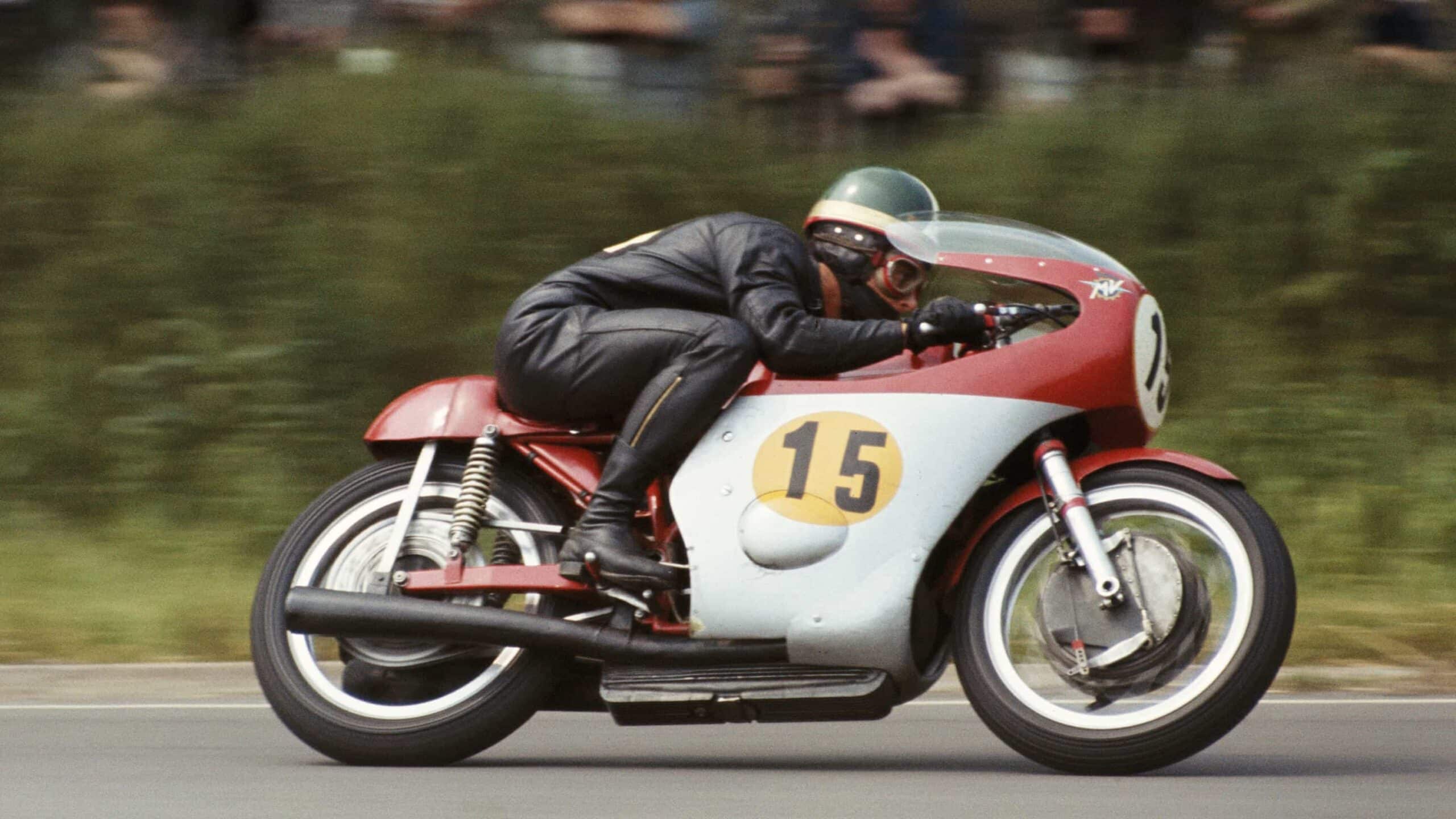

Agostini in action in 1965

The Isle’s scenic nature lends a stunning backdrop

Getty Images

Fans get up close to the action

IOMTTraces.com

Every lap is an adventure and the buzz is so high it’s almost spiritual: pure tunnel vision as you motor along in sixth gear, knees skimming hedges, elbows brushing walls, threading the eye of a needle, engine sound bouncing off buildings, sunshine strobing through a canopy of trees, creating a kind of real-world version of Star Wars’ Hyperdrive.

Or perhaps it has more to do with that old cliché: the closer you are to death, the more you feel alive. If you do crash at the TT you’ll likely be travelling at very high speed and when you go down you’d have to be very, very lucky to miss any of the usual roadside furniture of houses, walls, lampposts and trees. Thus the TT is to short-circuit racing what free climbing (without ropes and so on) is to conventional rock climbing – make no mistake, because your first mistake may be your last.

Whatever the attraction, it keeps riders coming back to tackle what they call the Everest of motorcycling. The speeds and risks – to most – are insane. The latest superbikes produce over 200 horsepower and exceed 200 miles an hour at the course’s fastest point, the 1.5-mile straight through Sulby village.

Even the TT’s greatest exponents acknowledge the fact that the TT is mad, but they also see it as an escape from an increasingly uniform and regimented world, in which the tendency is to exorcise risk from all walks of life.

“It’s mental, just mental, but that’s just the way it is,” says 25-times winner Michael Dunlop, who lost his father, brother and uncle to racing on the roads, but can hardly imagine his own life without the TT. That creates quite the paradox.

“This place is mad,” adds 23-times winner John McGuinness in No Room For Error, the TT’s antidote to the syrupy gloss of Formula 1’s Drive to Survive documentary series. “Obviously the danger side of it is off the charts. It’s going to be big if you go down here, it’s not going to be fun.”

And yet McGuinness, who’s been racing around the Mountain course since 1996, and every other TT rider consider the rewards – which are often more personal than financial – outweigh the risks. Therefore the TT is, if you like, a big fingers-up to modernity.

“Where in the world can you get 37 and three-quarter miles of road, close it off and race around it as fast as you want?” grins 2019 Senior TT winner Dean Harrison, who describes himself as a wall dodger, before quickly adding, “Hopefully…”

“It’s f***ing mad,” agrees 2019 Supersport winner Lee Johnston, who missed this year’s TT following a huge crash in May’s North West 200 races, staged around public roads on Northern Ireland’s north coast. “Imagine finishing the job you do for your living and being over the moon to still be alive!”

Sidecars in 1954

Getty Images

Peter Hickman

Michael Dunlop

The race start in 1962. Gary Hocking would win aboard an MV Agusta against a horde of Nortons…

Getty Images

The TT was the world’s biggest motorcycle racing event from the early 20th century until the mid-seventies, when the FIM (motorcycling’s FIA) removed it from the grand prix world championship, because top riders like 15-times world champion Giacomo Agostini and seven-times world champion Phil Read had refused to race there, for safety reasons. ‘Ago’ had led the revolt, following the death of his friend Gilberto Parlotti during the 1972 125cc TT.

Inevitably, there were fears among TT enthusiasts that the event was on the way out. Too dangerous for the world’s best riders, so how long before everyone else decided to steer well clear? But they never did.

There’s a certain breed, a closeknit sub-culture of motorcycle racers that’s drawn to the challenge of the Mountain. They’re mostly British or Irish, working-class, hard as nails and usually skint, because only the top few make any money out of the TT.

MotoGP riders and World Superbike riders are brave, but they’re different. They’re slick professionals who take their risks, like mountaineers with ropes, knowing that when they get it wrong they’ll most likely end up rolling through a gravel trap, not thumping into a brick wall at 140mph.

Some MotoGP riders hold TT racers in awe, while others think the all-too-frequent fatalities bring the entire sport of motorcycle racing into disrepute.

…Compared with the modern-day start. Times have changed, but the appeal remains

John McGuinness on his Honda

A rare shot of the car TT from 1908

Getty Images

It will hardly satisfy MotoGP safety standards, but padding a phone box offers something

Getty Images

When Italy’s seven-times MotoGP king Valentino Rossi visited the 2009 TT he presented McGuinness with the Superbike winner’s trophy and told him, “You are the true warriors”.

On the other hand, five-times MotoGP champion Mick Doohan made the pilgrimage to the TT a few years later and was less appreciative. “It’s frickin’ nuts,” he said after riding a lap on closed roads.

Both opinions are entirely valid.

“Where else can you close miles of road and race as fast as you want?”

Of course, there are frequent calls for the TT to be shut down. And when six competitors die in two weeks it becomes increasingly difficult to defend the existence of the event, not so much thinking of the riders who die doing what they want to do, but of the loved ones they leave behind.

However, in this day and age it is a glorious thing that people are allowed to take on challenges that carry such risks. And how come no one ever seems to suggest that mountaineers be banned from climbing mountains? The world’s most dangerous peak is Annapurna in Central Nepal. Only 191 climbers have made it to the top, while 63 have died in the attempt.

Some people will always seek risk in their lives, however high the odds.