Tough, terrifying and deadly — five years of the Carrera Panamericana

In an era of frequent deaths in motor racing, this dusty road race on Mexico’s newly built Pan-American Highway was treacherous. Doug Nye tells the Carrera Panamericana’s story

Klemantaski Collection/Getty Images

Carrera Panamericana: 1950-1954

Through the early 1950s the Mexican Carrera Panamericana proved itself to be the most inspiringly exotic, challenging – and positively dangerous – great public road race on the international sporting calendar.

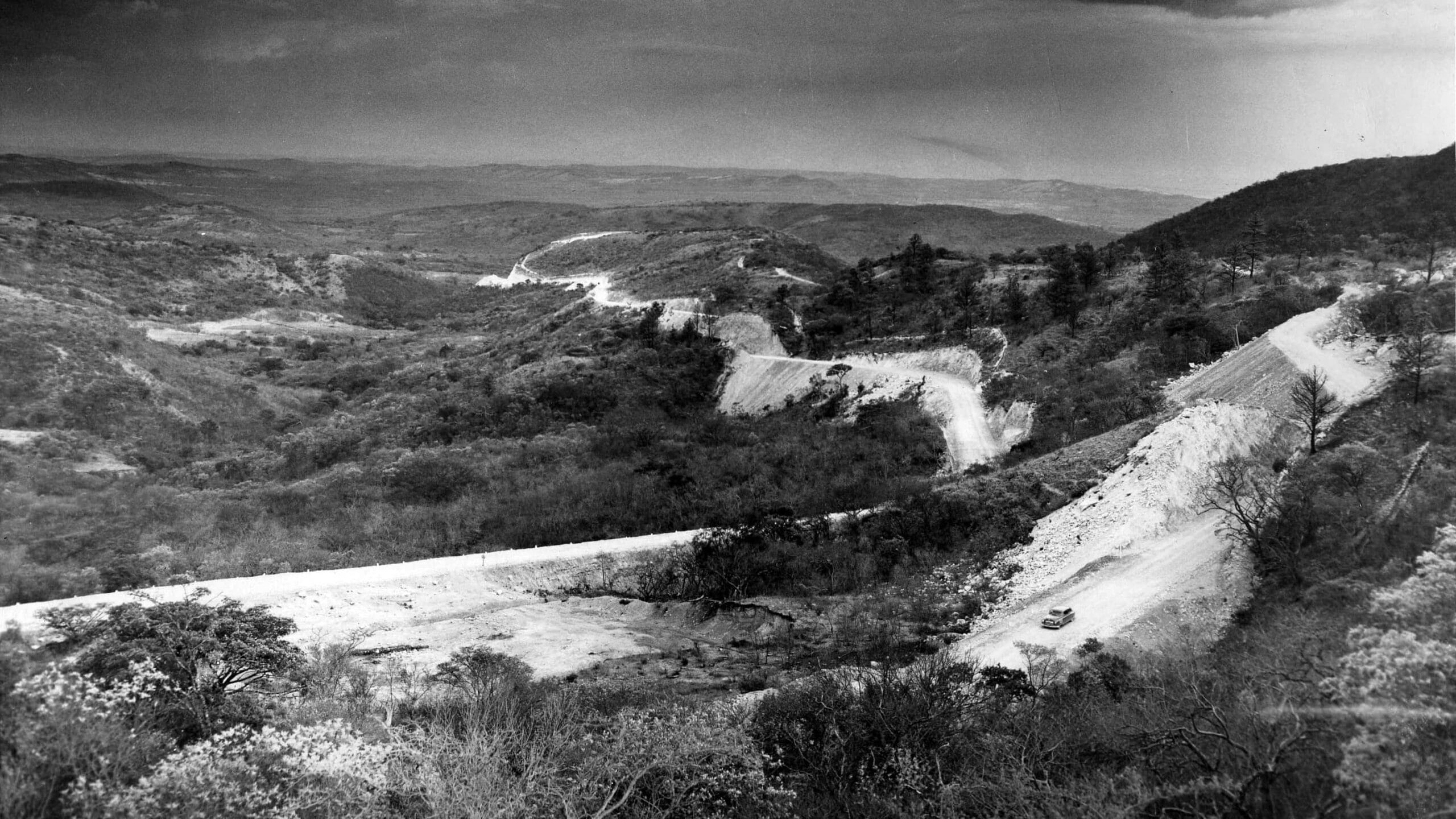

Politically it had been launched to focus world attention on Mexico’s completion of its section of the long-mooted Pan-American Highway – a continuous arterial roadway from Alaska down to Argentina’s Tierra del Fuego. A background agenda was merely to ensure rapid American access to the Panama Canal, but every involved nation was to contribute road sections across its territory – and by 1950 Mexico generated national pride by being the first to complete.

To celebrate, national communications ministry director Guillermo Ostos proposed a world-class motor race on the new road, from border to border. Mexico’s president Miguel Alemán approved. The story broke in March 1949. That June planning began, and an inaugural Carrera was announced for 1950, run north to south in nine legs, over six days, May 5-10 – 2135 miles. Entry to this inaugural Carrera was open only to minimum 550-run stock (production) cars with at least five seats.

The 1954 race winner Umberto Maglioli at the wheel of his Ferrari 375 Plus

McKlein

The prize fund, paid only to the top three finishers overall and in class, totalled $34,681 – $17,341 for first overall. American stock cars from Cadillac, Buick, Oldsmobile, Chevrolet, Lincoln, Mercury and Ford, even a pre-war Hudson and Cord, confronted transatlantic imports Alfa Romeo, Delahaye, Jaguar, Talbot and Hotchkiss. The race winner was American stock car star Herschel McGriff’s 5-litre V8-engined Oldsmobile 88. Advertising was allowed on every entry – and the garish, gruelling, perilous Carrera Panamericana had been born.

Italian stars Piero Taruffi and Felice Bonetto had been outgunned in Alfa Romeo 6C-2500s, but they would be back. A 1951 race was confirmed, run south-north this time in eight stages, 1934 miles. Four-seaters were admitted, closed-cockpit only. Ferrari fielded Vignale-bodied 212 Inter Coupés – really 2-plus-2 seaters at best – for Taruffi/Chinetti and Ascari/Villoresi. They finished first and second, Bill Sterling/Robert Sandidge’s Chrysler Saratoga stock car third – and the Carrera had assumed international stature.

This attracted Mercedes-Benz for 1952, when open-cockpit two-seat sports car entries were accepted. American interests pushed for a separate stock car category, the prize fund grew, works Mercedes 300 SL Coupés finished 1-2, Karl Kling/Hans Klenk victorious – the best Ferrari third (Chinetti/Lucas, Ferrari 340 Mexico) – while the first US stock car home was the Chuck Stevenson/Clay Smith Lincoln Capri, in seventh.

The fourth Carrera, in 1953, became the final round of the FIA’s brand-new Sports Car World Championship series. Crash helmets became mandatory! Lancia Corse shipped over a formidable works team… and finished 1-2-3, Fangio, Taruffi, Castellotti. Lincoln Capris finished 1-2-3-4 in the stock car category, Stevenson/Smith winning, again seventh overall. And so, to 1954…

“The reception of the Mexican people was very warm and ecstatic”

The 1954 edition of the great Carrera Panamericana was the fifth and final one of what had rapidly established itself as an even more gruelling motor racing challenge than the mighty Mille Miglia. That year’s race was run from November 19-23 as the sixth and final round of the annual FIA Sports Car World Championship, then in only its second year. As had become standard, the race was run south-to-north from Tuxtla Gutiérrez, in Chiapas state 100 miles from the Guatemalan border, to Ciudad Juárez, on the northern border with the US. From central Juárez to central El Paso, Texas, is barely six miles.

This 1954 Carrera was run in eight stages, over 3070km (1910 miles) – that’s right almost double the Mille Miglia… but not in one day. Some 150 entrants started from Tuxtla, 85 of whom would survive to finish at Juárez. Race winner would be Italian Ferrari works driver Umberto Maglioli in a brutish Ferrari 375 Plus powered not by the model’s standard 4.9-litre V12 engine but by one reputedly slightly enlarged to nearer 5.1 litres for this event. Ferrari’s US agent Luigi Chinetti arranged private sponsorship on the basis of finding customers to buy ‘the works entries’, providing – Mr Ferrari had specified – that Umberto Maglioli should drive one of them. His 375 Plus – chassis 0392 – had been sold via Chinetti to wealthy US enthusiast Erwin Goldschmidt.

When I spoke with Maglioli about the race several years ago he recalled: “My Plus was sponsored by 1-2-3 which was the biggest-selling detergent and cooking oil brand – owned by Mr Santiago Ontanon, who became a very good friend of mine.”

Stage 1 covered 329 miles from Tuxtla to Oaxaca along the Pan-American Highway, whose opening in 1950 had been celebrated by the foundation of the race itself. The route was hilly and winding before the mighty Tehuantepec Straight. Forget Mulsanne or the Mistral at Ricard-Castellet. Here we’re talking of 25 miles with only two mild curves – a perfect stage for the 180mph V12 Ferraris. From Tehuantepec at 328ft above sea level the course then climbed through a claimed 978 corners to reach 6500ft, before descending to the Oaxaca finish at 4600ft.

Not all of the Carrera Panamericana was on ashpalt; sand was a particular hazard

Getty Images

Nine private Ferraris started, driven by Maglioli, Phil Hill, Jack McAfee, Giovanni Bracco, Franco Cornacchia, Roberto Bonomi, Luigi Chinetti himself, the Marquis de Portago and celebrity playboy Porfirio Rubirosa. On the opening stage American driver McAfee crashed his John Edgar-entered 375 Plus, the incident killing passenger Ford Robinson.

Maglioli: “I was very careful under acceleration not to spin the wheels. It was vital to preserve the tyres… I did not want a blow-out. That first stage had a very bad surface – local stones which had sharp edges, like razors. If you drove too hard you needed two tyre changes. I had two arranged, which meant I used 12 tyres to complete that stage. I had chosen to drive alone to save weight and improve aerodynamic form. Under the rules when I reached my depot I had to change all my wheels unassisted…”

Phil Hill was accompanied by his diminutive mechanic friend Richie Ginther in a 4.5-litre Ferrari 375 V12 which Chinetti had sold to American entrant Allen Guiberson. Phil drove with panache and won that opening stage by 4min 9sec from Maglioli.

Next day Stage 2 was run in two legs, Oaxaca-Puebla, then Puebla-Mexico City – total 328 miles, and the most mountainous stage of all, rising to 10,382ft. By the town of Atlixco, Maglioli had slashed Hill’s lead to 1min 9sec, and at Puebla was 4min 15sec clear, only for a puncture to lose him that margin. Phil covered 75 miles from Puebla to Mexico City in 47min. Maglioli had lost his car’s boot-lid and headrest fairing, coming home 45sec slower with his car’s fuel tank and spare wheel exposed.

Maglioli: “The second section into Mexico City was terrifying. For the last 15-20km a million Mexicans lined both sides of the straight… the front rows no more than 5-10cm away from the cars each side… It was like racing through a riot!”

November 21 – 590 miles in two legs, first to Léon then Durango. After a lengthy emergency sparkplug change (all 24 of them) pre-start, Maglioli covered the 261 miles at over 110mph average. Phil Hill, outgunned, lost 3min 46sec. Maglioli: “The real problem was blowing sand and the mirage effect. Sand on the road made it unexpectedly slippery, like driving on ice – while mirages at 270-280kph played tricks with your eyes. I had a drinking bottle but it was ’orrible and chewing gum but nothing else. No passenger to serve lunch…”

Léon-Durango, 329 miles, only 95 finishers there; Maglioli 3min 12sec ahead of Hill, extending his overall lead to 6min 18sec.

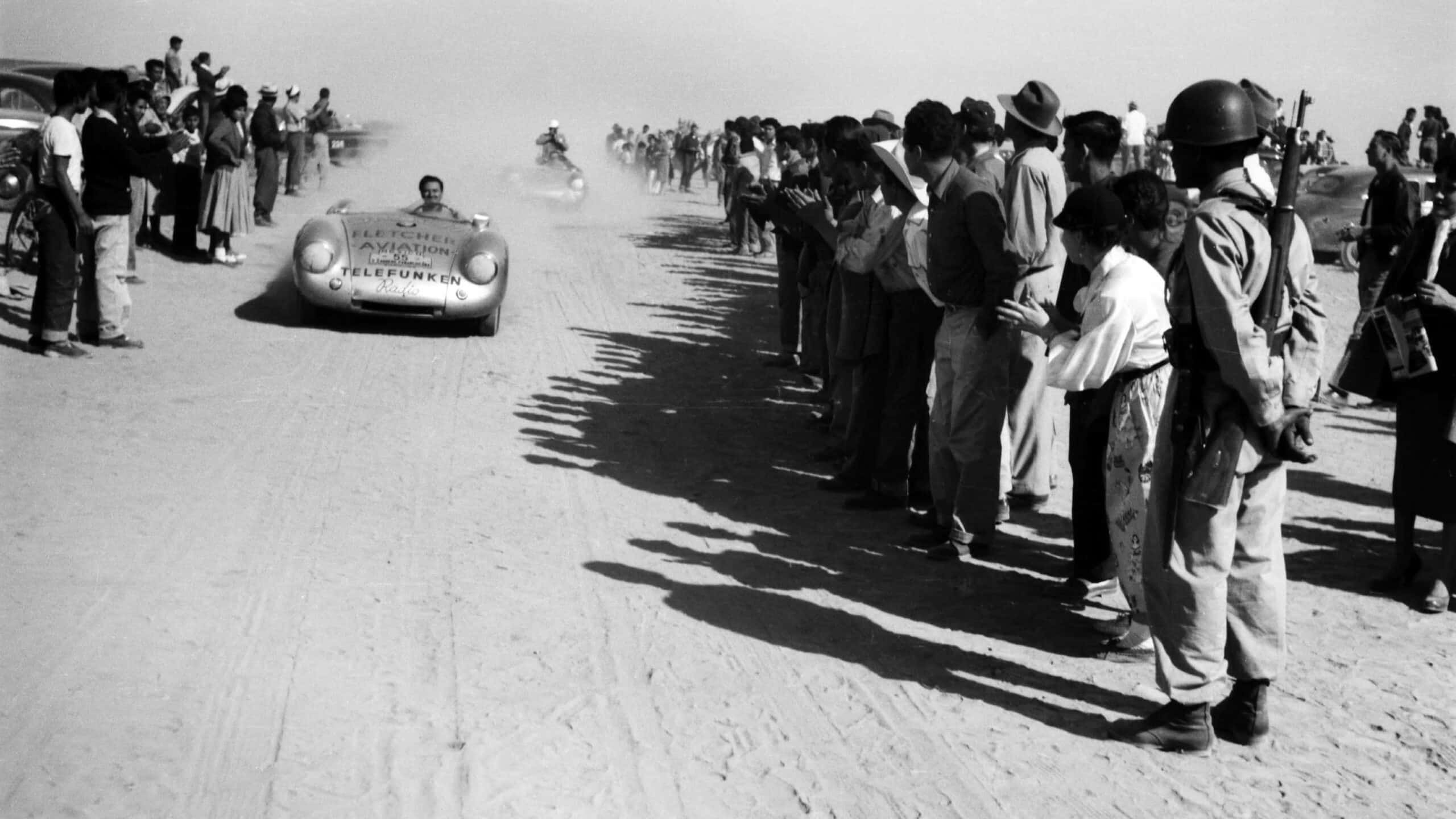

It’s the end of a dusty stage for Hans Herrmann in his Porsche 550 Spyder in 1954 – he’d finish third

November 22 – 437.5 miles Durango-Chihuahua – perhaps the smoothest-surfaced section of the Pan-American Highway, and one with 20-40-mile straights across rolling ranchland. Maglioli held 160mph-plus for long periods. Having set the record time the previous year on this section, he now lowered it by 50sec. While his engine ran near perfectly – apart from losing some coolant – Phil’s 4.5 was beginning to wilt. Over 186 miles from Chihuahua to Parral, Umberto averaged 127mph. The Ferraris of Chinetti and Cornacchia displaced Hill/Ginther to fourth place. But Cornacchia’s had a damaged crown-wheel, Chinetti’s had an oil line part and Hill’s left-bank magneto was faulty.

Maglioli on his car’s troubles: “The top rubber hose from the engine to the radiator had split and was losing water. Fortunate it was not the bottom hose because that would have drained the system completely – the top was survivable”.

Phil Hill: “After finishing the stage, Richie complained his door was jammed solid. I walked around and gave it a great yank. It burst open… and the back of the car fell clean off! The only thing left holding the tail on had been the pin latching the door. So we had that to fix too.”

November 23 – final day. Chihuahua to Ciudad Juárez on the Rio Grande, virtually dead straight, and lined by many thousands of spectators. Maglioli’s red Ferrari howled past the chequered flag at 134mph – barely 3sec ahead of Phil’s smaller-engined white sister car. Eight minutes passed, Chinetti flashed under the finish banner, and 3min later Cornacchia. Umberto Maglioli had won overall in 17hr 40min 26sec, at an overall average speed of 107.96mph, Phil Hill an honourable second in 18hr 4min 50sec.

Third and fourth overall proved to be Porsche 550 Spyder drivers Hans Herrmann and Jaroslav ‘Jerry’ Juhan – many years later to be involved as a ‘facilitator’ in the Colin Chapman/John DeLorean scandal. Cornacchia finally placed fifth over 41min adrift, and the beaming Chinetti – for he had trousered sales commission on all four prominent Ferraris –sixth, some 12min further adrift.

Maglioli recalled: “The reception of the Mexican people was memorable, very warm and ecstatic. It made me feel almost like Pancho Villa, you know? A big hero. It was a very pleasant experience. And by the standards of the period – the prize – perhaps $10,000 – far more even than for winning the Mille Miglia back home!”

But the Carrera’s days were numbered. With its combination of super-fast straights, precipitous and wooded mountain sections, tyre-shredding road surfaces, uncontrolled spectators and many underqualified drivers – the race had claimed at least 31 lives from 1950 to ’54.

A sixth edition was planned for 1955, but when international racing was rocked to its core by that June’s Le Mans disaster, national governments imposed crack downs, even, in Switzerland’s case, completely banning motor racing.

In Mexico the Carrera’s organisers had always struggled to police the event adequately. After rainy season road damage, Mexican president Adolfo Ruiz Cortines resisted paying the cost of highway resurfacing necessary for another race to be run. European governments’ reaction to Le Mans provided a perfect political smokescreen to avoid such cost, by banning the race instead. In August 1955, the axe fell – and La Carrera Panamericana died.