A fairytale result overshadowed by ghastly tragedy: the last Mille Miglia

Barring a world war, it ran for 30 years – until one final disaster. Doug Nye explains how the Mille Miglia earned its gruelling reputation, and the bravado that snatched the final victory

Getty Images

Mille Miglia: 1927 – 1957

It has been asked, what did the Romans ever do for us? Around 29BC Agrippa had the Roman mile standardised at 1620 yards. Two millennia later, Benito Mussolini’s Fascists obsessed about establishing a prestigious new ‘Roman Empire’. From 1933 fellow narcissist Adolf Hitler followed a similar route in German terms. For both, motor racing seemed an ideal stage upon which nation and national industry could strut.

While the French had firmly established their great Grand Prix de l’ACF, in 1906 – the first truly national motor race to join it as a perennial series was the Gran Premio d’Italia, first run near the Italian industrial city of Brescia in 1921. When the infant Gran Premio was moved to Milan’s new Monza autodrome for 1922, proud Brescians felt slighted.

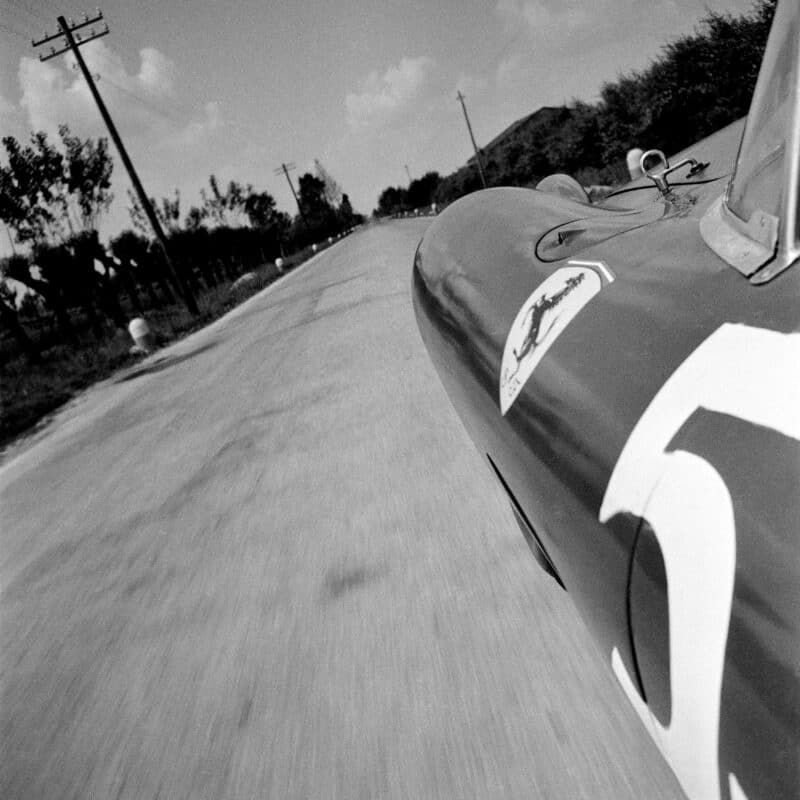

Riding with Collins

Counts Aymo Maggi and Franco Mazzotti combined with local sports manager Renzo Castagneto and motoring journalist Giovanni Canestrini to create a spectacular rival race from Brescia to Rome, then back to Brescia; close to 1000 Roman miles – literally ‘Mille Miglia’. The new race was first run in 1927, rapidly becoming the most prestigious sports car event of them all, in period, exceeding even the four-years older Le Mans 24 Hours.

It ran annually from 1927-38, when an awful accident left 10 spectators dead and 26 injured. Not run in 1939, a diminished version re-emerged over nine laps of a 62-mile public road loop – Brescia-Mantua-Cremona-Brescia – in 1940. As early post-war as 1947, il vero Mille Miglia (round-Italy) was revived; Alfa Romeo winning for the 11th time. The new Ferrari marque won six more in 1948-53, before double defeat by Lancia, then Mercedes-Benz, 1954-55. In 1956, Ferrari made it seven.

Taruffi congratulated by his wife, Isabella, after his victory.

Getty Images

And so to 1957. Ever since that year’s 24th ‘proper’ Mille Miglia, it has been recalled more for a ghastly accident, than for its near fairy-tale result… Within 30 minutes of the winner crossing the Brescia finish line, news flashed in from Guidizzolo, 25 miles back. Ferrari’s 28-year-old Spanish driver, the Marquis ‘Fon’ de Portago, his American passenger 40-year-old Ed Nelson and nine spectators – including five children – had been killed following an Englebert tyre burst at 150-160mph. Within days Italy’s great road race was banned irrevocably. Bare months had passed since the death of Enzo Ferrari’s son Dino. Now the still-grieving father found himself blamed for the catastrophe, vilified by the press, the Catholic church, the Pope himself.

But more happily, consider one man’s racing story of that last ever ‘proper’ Mille Miglia. By 1957, 50-year-old Piero Taruffi – ‘The Silver Fox’ – was an Italian racing icon. He had contested 15 Mille Miglie. He had longed to win, but third for Alfa Romeo in 1933 and fifth for Maserati ’34 had been his best. Now Mr Ferrari had invited him to drive a works-entered 3.8-litre 4-cam V12-engined Ferrari 315 Sport – then to retire, alive…

Shot at 180mph, Klemantaski’s images alongside Collins are stunning.

Taruffi: “Luck had never come my way. Twice I crashed, with Lancia and Maserati, but three times, always in Ferrari, transmission failure. In 1957 I set out feeling marvellous. I knew the course by heart; my race number was ‘535’ – for me lucky, because it added up to 13! Behind me was no one formidable except Moss [Maserati 450S]… but he retired shortly after the start. I caught [team-mate ‘Taffy’] von Trips before Pescara, just as [team leader Peter] Collins completed his fill-up.”

Taruffi attacked on the 405 miles from Pescara to Bologna, on challengingly twisty Appenine roads. He saw vivid black tyre marks from wheel-spin: “It could only be Collins, as I had already passed Trips. Absolutely determined to finish this time, I started the Pescara-Rome stretch with great care. To spare the transmission I used the high gears and avoided changing gear [for] corners.

“Those few bends had sealed my victory, most coveted of my life”

“At Rome I had lost five minutes to Collins; I should have to hurry… On acceleration, the wheels bouncing off the ground, my rev counter often went past the limit. [But] by Viterbo 50 miles on I had not gained much; I realised that, even if I kept it up, I could not catch him and might well come unstuck…

“Between Florence and Bologna the transmission began to make a nasty noise. ‘This is it’, I thought. At the Bologna control it was raining. Ahead lay the long straight sections of the Via Emilia, slippery in places. Full throttle in fourth at 125mph [caused] wheel-spin. I had decided to stop, when I learned from Ferrari himself that 20 miles on the rain had stopped. When I heard Collins had transmission trouble I restarted [as] a loudspeaker announced von Trips was passing through Livergnano 10 miles behind. I tried to avoid gear-changing and to accelerate gently, easy because there are few corners Bologna-Brescia. I kept down to 130mph.

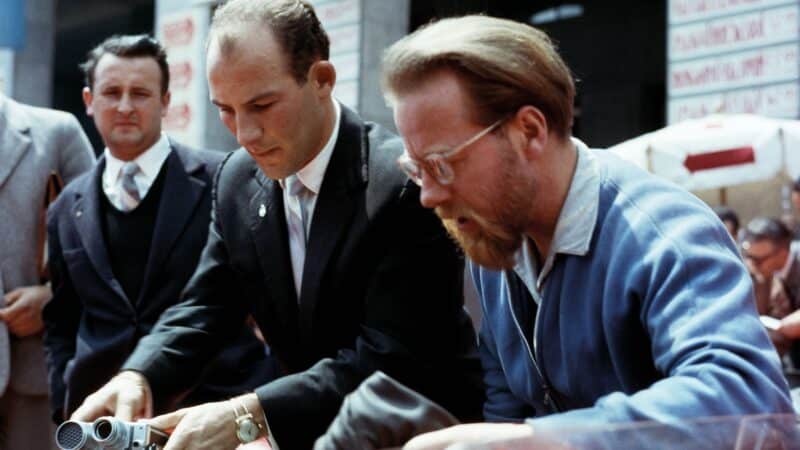

No repeat glory for Moss and Jenks, who retired with a broken brake pedal on their Maserati

“With less than 60 miles to go I began to glimpse a red car in the mirror… it caught me… von Trips. I made a rapid calculation; we still had half an hour to go… I had a lead of three minutes. If von Trips could average 12-15mph more than me he would win, and as there were no team orders he might well do so. I sped up to 150-155mph and waved him down, he obliged for a bit. Finally he made overtaking signs and came past. We were just coming into Piadena. Because it formed part of a special timed section…” [for the Gran Premio Nuvolari, fastest time over 82 miles Cremona-Mantua-Brescia] “…I had made a special study there. After a long straight of about 2 ½ miles (the road weaved through Piadena).”

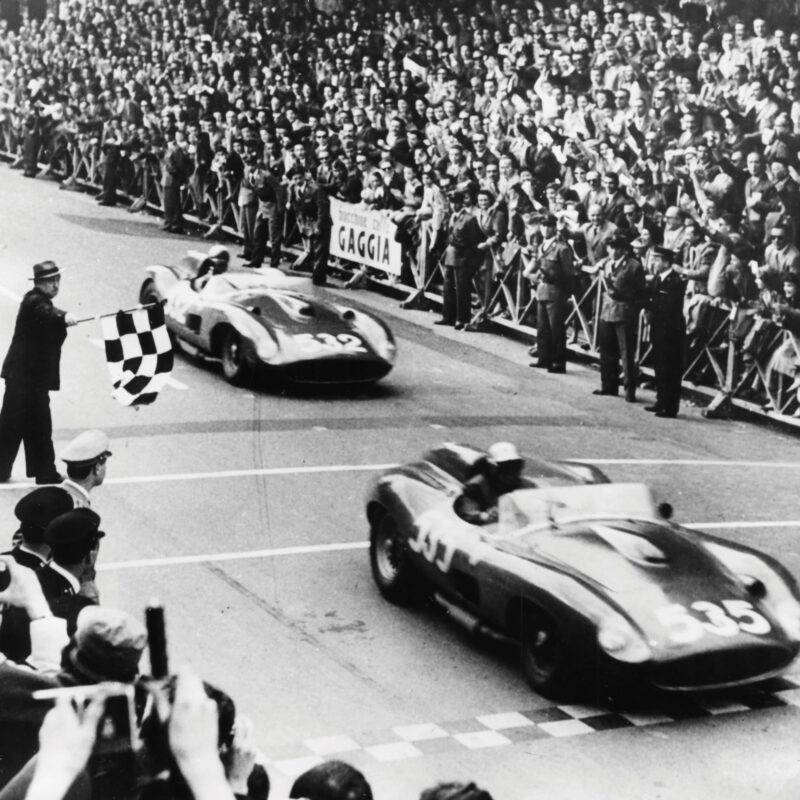

Taruffi leads von Trips across the line in a formation finish.

Getty Images

He knew that in one turn he could use a layby there – if vacant – to take a faster line. “On the apex of the bend there was a big house with a collonaded portico. It seemed to block the view but… by looking through the outside arch one could glimpse the line [and] gain time by using the lay-by [beyond]. About 450 yards, another ‘blind’ left-hander about 10mph faster… the same with the next bend [then] straight for more than three miles. As we approached Piadena, Trips, who had been driving hard to shake me off, was about 200 yards ahead… about 100 yards short of the esses he… braked. I realised I could pass. I… aimed left and across the lay-by. Looking through the portico the road was clear. I lifted very slightly, 150 yards and accelerated again at 50 yards. From there I did not lift at all – Trips was only a few yards ahead… I was able to pass him on the run out. In those few yards I had not only wiped out Trips’ lead, but also given him the impression I was the better driver… I signed to take it easy, and he very sportingly did so. I did not know it yet, but those few bends had set the seal on my victory, the last and most coveted win of my life…”

Ferrari team leader Eugenio Castellotti ahead of the 1955 race. He would be killed shortly before the 1957 edition

At the finish line Taruffi and Trips took the flag in line astern. ‘The Silver Fox’ was engulfed. His wife Isabella embraced him. He gasped how wonderful it was to have finished for once. “But you’ve won, darling! You’ve won!”. Taruffi: “Not believing, I made her repeat it again and again… Collins, after leading for most of the race, had blown up 125 miles from the finish.”

And the great Piero Taruffi then began his long, much-respected, retirement, winner of the last Mille Miglia. It was fitting. Born and bred, he was a Roman.