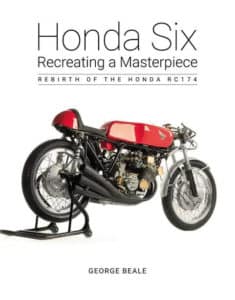

Honda Six: Recreating a Masterpiece book review

When just two examples of a bike exist, it’s time to get creative. Simon de Burton reads how a Honda Six enthusiast built a racing continuation

A word of advice: don’t lie in bed beside your wife looking at a photograph captioned: “The distinctive contours of the Honda Six cylinder head after four-axis machining…” It sends out all the wrong messages. I know. I did it.

But having been enthralled by the Honda RC174 ever since writing about classic bike guru George Beale’s project to ‘continue’ it 15 years ago, there was no way I wasn’t going to read this recently published book on the subject.

For anyone unfamiliar with the RC174, it has long been (to quote Sir Winston Churchill) something of a riddle wrapped up in a mystery inside an enigma.

Its story dates back almost 65 years to Honda’s first appearance at the Isle of Man TT in 1959, an outing at first thought to be a rather quaint attempt to try to compete with the big boys such as MV Agusta and MZ in the 125cc ultra lightweight class.

It ended with Honda finishing a respectable sixth – but what few people appreciated was that the indomitable Soichiro Honda had determined to plough all his resources into racing and returned to the island in 1961 to win both the ultra-lightweight and lightweight TTs with bikes ridden by Britain’s Mike Hailwood.

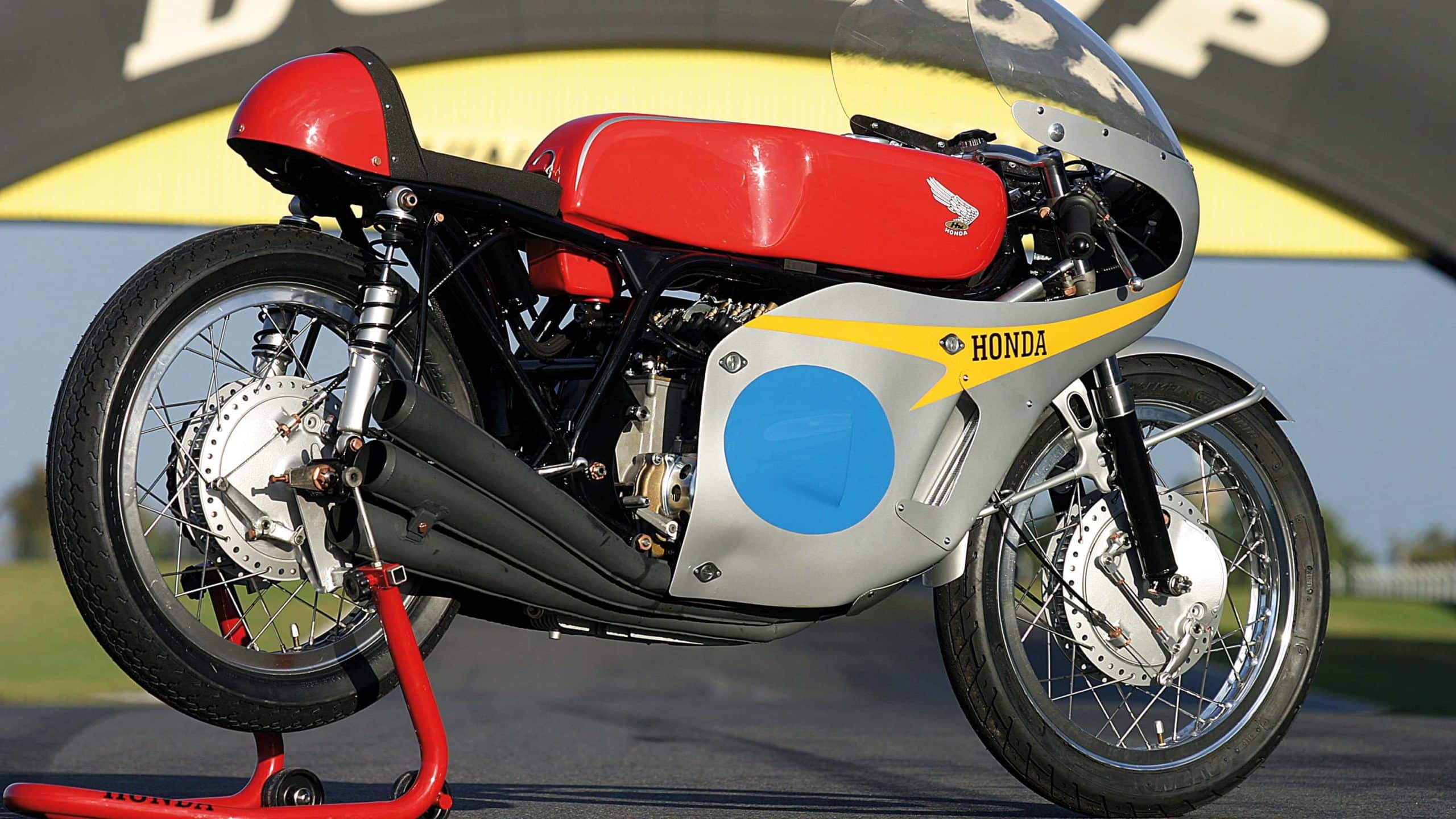

It was in 1964, however, that Honda truly stunned the two-wheeled world by introducing its 3RC164, a 250cc, in-line six that amazed competitors and riders alike with its complexity, performance, 20,000rpm red line and banshee-like sound.

Just six were made, and it was these that spawned the even rarer, faster model for the 1967 TT – the RC174, which was essentially the same bike but with a slightly greater engine capacity that qualified it to compete in the 350cc class.

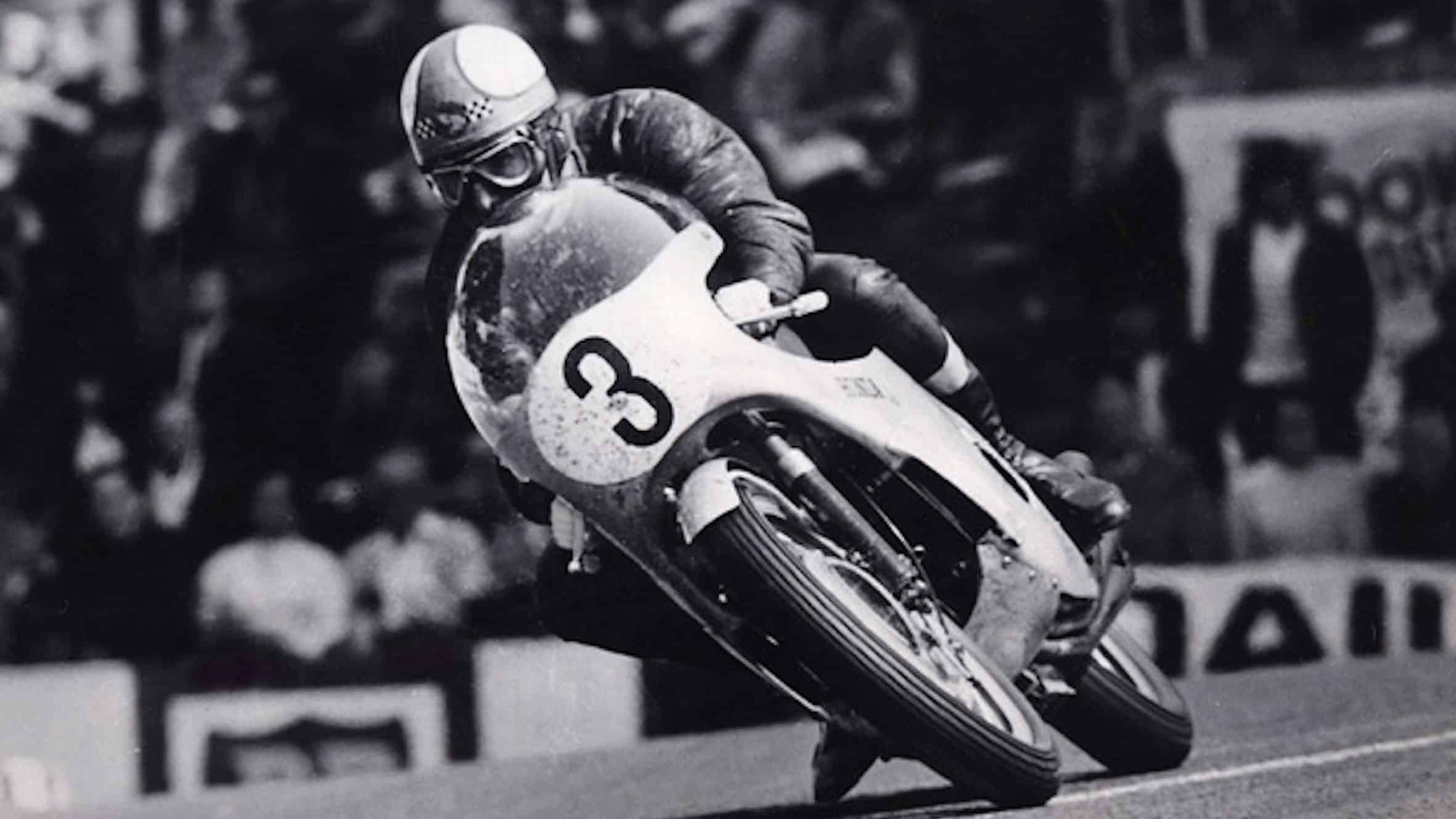

Built for Hailwood’s use, he delivered the goods by taking the chequered flag ahead of Giacomo Agostini’s MV Agusta at an average speed of 104.68mph.

Just two RC174s were originally made, one of which is kept in the Honda Museum, the other of which belongs to Japanese collector Terry Murayama.

Mike Hailwood on his way to victory in the 1967 350cc Isle of Man TT, averaging 104.68mph

He acquired it during the 1980s in exchange for 43 British machines and an undisclosed amount of cash – the combined equivalent value being sufficient to have bought two houses in Tokyo.

In the opening pages of the book, Beale explains how Murayama, a former schoolteacher, had discovered the bike in the hands of a motorcycle dealer close to his home in Japan.

The dealer’s connections to Honda’s race department had enabled him to buy the bike when it was regarded as defunct – not long after the close of the ’67 season, during which the two RC174s had brought Hailwood wins in the West German GP, the Isle of Man, the Dutch TT, the East German GP, the Czech GP and the Japanese GP.

|

Honda Six: Recreating a Masterpiece

George Beale Charterhouse, £65 |

When Murayama discovered it at the dealer’s, however, it was “complete and just sitting on the floor in a very miserable state”.

He and a friend collected the chassis and engine separately because their only transport was a Honda S600 hatchback, after which Murayama re-assembled the bike in his workshop, hid it in his cellar and embarked on an almost fanatical quest for information about its origins.

That included acquiring 1300 Honda Six drawings, befriending the now-late Masahiro Satoh (designer of the celebrated Honda 400 Four road bike and one-time manager of the Honda Museum) and discovering that the bike he had acquired was the actual machine on which Hailwood had won the 350 TT.

The book explains that it was through Satoh that Beale was able to obtain Honda’s permission to attempt to recreate the RC174, and it was thanks to Murayama’s generosity in having his original bike shipped to England to serve as a guide and template that the project could be instigated.

George Beale demonstrates replica No2 aided by collector Terry Murayama

In 235 pages – many rich in large format, period photographs – Beale recounts the 25-year labour of love (and all the ups, downs and frustrations that went with it) that enabled him to build 10, millimetre-perfect RC174 recreations. He relates how it cost him more than £200,000 just to get the project off the ground; how it took genius engineer Julien Charnolé of French Formula 1 parts manufacturer JPX in Vibraye four-and-a-half years to overcome myriad conundrums in order to be able to complete the first replica engines, and how every single ancillary component – including the bank of six tiny Keihin carburettors and numerous other exotic parts – had to be re-manufactured from scratch.

The book draws to a close with stories of the completed replicas being shaken down by top classic bike racer John Cronshaw, with some subsequently being ridden by contemporary stars including Guy Martin and John McGuinness.

Edited by highly respected motorcycle racing journalist Andrew McKinnon – a long-time friend of Beale – it’s a must-read for anyone who finds the story of Honda’s beginnings on the track as fascinating as its founder’s unrivalled genius for engineering.

But don’t forget: read it in the workshop – not the bedroom.

Allard – The records and beyond

Gavin Allard

Had Bill Boddy still been around he would have been glad of this two-volume work, effectively the company archives nicely presented in two volumes. Good friends with Sydney Allard, WB could have used it to check the ID of any Allard that came up in our classifieds. Apart from some memoirs in Volume 2 it’s not a reading book – much of it is lists, build sheets and service records from the company files, a lot of it hand-written, so owners of one of these mainly US-powered devices can track their car’s history. What enlivens it are the extensive photos, many previously unseen, of the 2000 or so varied cars built, allied to a lot of material from Sydney’s competition career – programmes, passes, reports, design sketches and the seminal dragsters. Specialist, but a valuable marque repository. GC

Dalton Watson, £130

Bristol 408

James Nichols

Bristol cars have always been a by-word for British engineering excellence but are also redolent of a bygone Wodehousian world of gentleman’s clubs deftly characterised by this fascinating if slight book: “The cabin of a Bristol is as much a place to hide from the harsh realities of the outside world as the Drones Club was for Bertie to avoid Aunt Agatha.” The book tells the story of the Bristol 408 arguably the peak of the company’s limited output (it averaged less than one car per week in the 1960s) as well as the discovery and restoration tale of one example. Author James Nichols writes with style and economy and while there are enough pictures to showcase the understated class of the 408’s lines (and its Chrysler V8 engine) there are few period shots. Mind you, the chapter on magazine coverage of the car makes up for that with a series of rag-outs from titles as Motor and Cars Illustrated. A small gem of a book even if you don’t own a Bristol – or like Wodehouse. JD

Amberley Publishing, £15.99