Le Mans victory that earned Graham Hill the 'Triple Crown'

It’s been 50 years since Graham Hill and Henri Pescarolo won the Le Mans 24 Hours, securing the British driver a historic motor racing hat-trick that nobody has matched. Pascal Dro spoke to the Frenchman, now 79, about that memorable weekend, when he scored the first of four wins at La Sarthe aboard a car he never intended to drive, with a team-mate he didn’t want

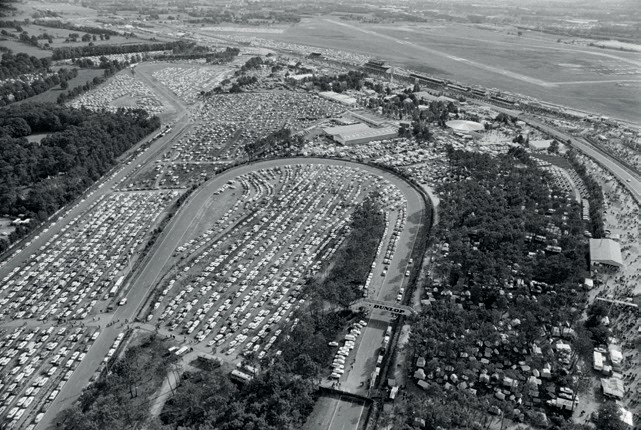

The crowd figures for the 1972 Le Mans 24 Hours vary, but we can safely assume two things: firstly, that it was north of 150,000 strong; and second, that few of them realised the exact measure of the piece of history they were witnessing unfold before them.

Graham Hill – already twice a Formula 1 world champion, five times a victor at the Monaco Grand Prix and winner of the 1966 Indianapolis 500 – became the first, and only driver, to complete the ‘Triple Crown’ by adding his name to the Le Mans roll of honour.

Of course, he didn’t do it alone, sharing the No15 Matra-Simca MS670 with a 30-year-old Henri Pescarolo. And the win made history for more than just Hill’s achievement.

Without a French winner since 1964 (or since 1950 if you were talking about the constructor) Pescarolo and Matra’s victory broke the Anglo-Italian-German stranglehold that had lasted over two decades at La Sarthe.

Pescarolo aboard the MS670 in the Le Mans pitlane.

It also wrote the first chapter in Pescarolo’s stunning career in the race. With 1972 being his sixth attempt at Le Mans, Pescarolo would go on to rack up a record 33 starts before his retirement after the 1999 edition, celebrating four wins along the way.

This was a race of huge significance for both British and French interests, especially with the Ferrari factory team opting to skip the event having already won the World Sportscar Championship, leaving Matra as the firm favourite. But the result so nearly didn’t come to fruition. Pescarolo, who had been a keystone to Matra’s Formula 1 activities in the 1960s, suddenly found himself frozen out and was due to race an Alfa Romeo instead. He was only called back when the team expanded to field a fourth car for Hill. Already seething with his former employer, the prospect of sharing with a 43-year-old ex-F1 driver didn’t fill Pescarolo with enthusiasm. However, he begrudgingly accepted, and in doing so secured a front-row seat for what has gone on to become a milestone in motor racing history.

This is his side of the story.

Henri, Le Mans 1972 now looks like such a straightforward success story, but at the time there were a lot of issues in the background, some big enough that they almost stopped you from racing that year.

“By 1972 I was no longer supposed to be driving for Matra. In effect I had been sacked in 1971, even though that wasn’t supposed to have happened. That scumbag Jabby Crombac [the Swiss motor sport writer] told Matra boss Jean- Luc Lagardère, ‘That Beltoise is no use, you’ll never win anything if you keep him – I’ll find you a decent driver.’ He sought out Chris Amon, lead driver at March in 1970, and Matra poached him for a sum that would seem derisory nowadays but was quite a lot at the time.

Hill was desperate for the win – and knew Matra was his best chance

“And that was that – they decided to keep Jean-Pierre Beltoise while I found myself out of a drive, even though I’d done a pretty good job with that heap of junk MS120. After that, I didn’t want anything to do with Matra. For me, it was all over. After having set so many records with them in Formula 2, after almost winning the European championship in ’68 and after having spent four months in hospital for trying to develop a car of theirs that wasn’t exactly terrific, the only reward I received was to be fired. For 1972, I accepted an offer to drive an Alfa Romeo for Scuderia Filipinetti.

I didn’t want to hear another word about Matra. As far as I was concerned, they no longer existed.”

So what brought you back?

“The same Jabby who had contributed to my sacking, even if that hadn’t been his intention.

He came up to me and said, ‘We’re planning to run four cars at Le Mans in 1972, in a bid to win, and you need to be part of the team.’

Pescarolo in action, in front of the sister car of François Cevert. Cevert had an oddly slow start from pole, and deliberately so, believing it bad luck to lead the opening lap

“After all the work I did for Matra, the months in hospital, the only reward I received was to be fired”

I sent him away, told him I no longer wished to talk about Matra, particularly after what he’d done to me. But he persisted and persisted. Finally, I said to myself, ‘Look, you could be a prize idiot here. You played a key role in Matra’s rise to prominence, you worked harder on its cars than anyone else and now that Matra might challenge to win at Le Mans, you’re going to be a prima donna and tell them to get stuffed?’ After all that effort, all that development and all that work, it occurred to me that it would be stupid to turn them down on a point of principle.

Finally, then, I accepted.”

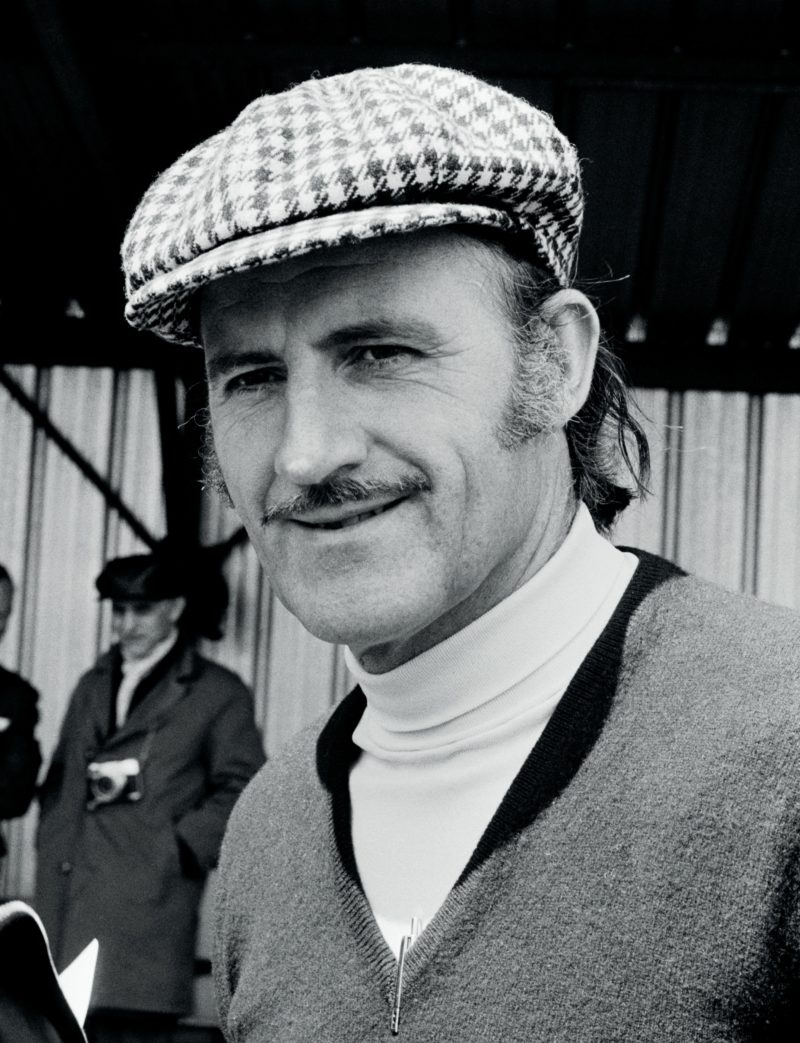

François Cevert in his prime.

So, what happened when you heard you’d be sharing with Graham Hill?

“That’s when it all kicked off again. I told Jabby that if Graham was my team-mate, I wouldn’t be coming. It was out of the question. I’d have been happy to share with Jean-Pierre [Beltoise], François [Cevert] or [ Jean-Pierre] Jabouille, but I didn’t want to drive with Graham. So Jabby told me to consider more carefully. ‘Look, he has been world champion, he has won the Indianapolis 500 – and nobody has ever done that and won Le Mans. And he really wants to win.

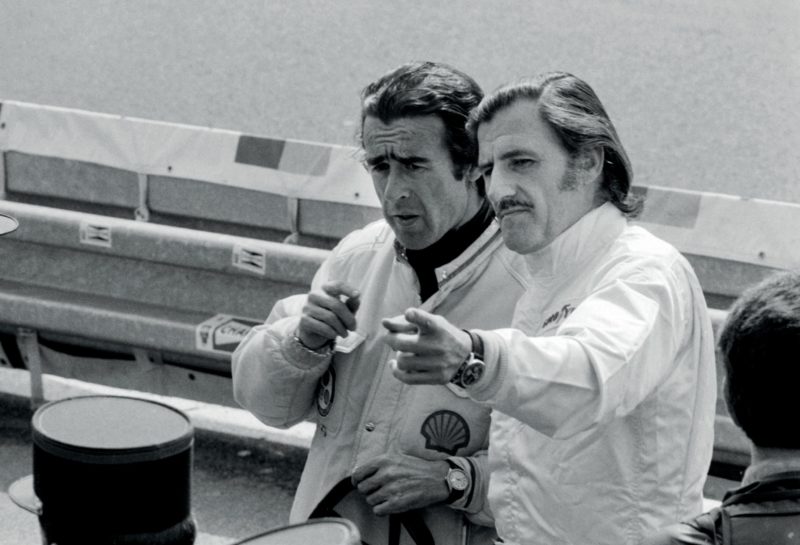

Graham Hill with Matra chief Jean-Luc Lagardère at La Sarthe, 1972.

You have seen him in F1 and F2. You know very well how good a driver he is.’

“No arguments there, but all I could think about was his age [Hill was 43 at the time]. In my eyes, I was a young charger and he was ancient. I knew that as soon as there was rain or fog, or darkness descended, he’d want to go and take a nap. But Jabby insisted that Graham was doing it because he really wanted to win, so eventually I agreed.”

Did you test the car together before the race?

“I don’t think so or at least I don’t remember! I’m fairly sure we didn’t.”

So he would have arrived at Le Mans without having shown any great prior motivation to win the race, nor having done any testing…

“That’s how I remember it – and there were some experienced drivers in the team too, not least François Cevert, who qualified on pole.

“The team planned for slicks, but Graham insisted on rain tyres”

I remember one particularly surprising thing about that. François took the lead at the start, but I was able to pass him during the opening lap. I could see that he was deliberately trying not to push. After the race I went to find him, to ask what he’d been doing during those first few moments. He replied, ‘D’you know something? Never in the history of Le Mans had the car that led the opening lap gone on to win the race.’ He was so superstitious that he did everything he could to make sure he was lying second, which seems crazy. After that it was a fairly lively race – especially as we had been given team orders. And the consequence of that, of course, was that we all did our best to ignore them!”

Were the drivers supposed to stick to pre-arranged race positions?

“No, it was more a case of setting predetermined lap times. There was no designated number one crew, no favouritism. That said, you knew when they put Cevert in one car that it was going to be quick, ditto Howden Ganley [his co-driver]. But I remember that Jean-Pierre [Beltoise] and Amon had a problem – Jean-Pierre was convinced of as much but Amon thought the opposite. They even went to do some tests on the runway at the airfield across the road, to be certain one way or the other. They didn’t find anything particularly wrong, but the problem reappeared very early in the race [the engine expired after two laps].

The Matra photo finish

The other important point about this race was the absence of Ferrari. Lagardère had put together everything he needed to win Le Mans, but also to beat Ferrari. But in the end Ferrari didn’t turn up, because they’d discovered that the 312 wasn’t capable of lasting 24 hours.

Happily, they did turn up the following year, when we were able to beat them at Le Mans and in the championship.

A packed Circuit de la Sarthe from the air

In 1972, the [Ecurie Bonnier] Lolas established themselves as our closest challengers early on, while the Alfa of Andrea de Adamich was also running well. At the first stops, however, Graham struggled to strap himself in and we lost time, which allowed François to retake the lead. Graham finally got going and when it came to my next stint I drove flat out to catch the leader. At that point, they began showing me ‘slow’ boards when I passed the signalling pits, so I had to back off.

“I’ll spare you the details about our brake wear issues, because we were getting through discs faster than the others, for reasons I don’t know, and various other minor details that affected our race, but we were lying second to the No14 car [Cevert and Ganley] when night fell… and then the rain came, along with my worries that Graham’s eyesight might not be up to the task in difficult conditions. But that’s when he excelled. It was no longer raining next time he pitted, but there was some drizzle. The team had planned to give him slicks, but he insisted they give him rain tyres.

He then returned to the track, made up our deficit and put us back in the lead.”

Here: Hill’s tyre call in mixed conditions was crucial to the car’s success

Did that decision save you an extra stop?

“I don’t recall, but we regained the lead thanks to his tyre call and his subsequent pace in the wet – but then we started to have some more braking difficulties. Despite that, we remained in contention for the lead with Cevert and Ganley. And as it was raining, there was no longer any prescribed lap time to adhere to. All of us were pushing like crazy, despite the conditions, and I’ll underline once again – that’s when Graham excelled. To be honest, that was probably the only approach to take. And then Jo Bonnier had his fatal accident, which cast a shadow over the race.”

The race wasn’t stopped?

“No. In those days, races were never interrupted. It wasn’t like the bogus form of the sport we see today. Rain or no rain, there were no safety cars or anything like that. It was proper racing – and you can quote me on that, because it’s what I think. Accidents were a part of the sport. Our lead battle continued – and I don’t remember whether the others had made a wrong tyre choice, or hadn’t changed at the right moment, but their car was eventually caught out on slicks in the rain when it was still dark. While Ganley was crawling back to the pits, Marie-Claude Beaumont [sharing a Corvette with Henri Greder] smacked straight into the back of it, necessitating bodywork and suspension repairs when the car finally got back.”

Did you then just pace yourselves to the finish?

“Exactly. We just had to make sure we didn’t commit any errors. It was a fabulous moment for me, even if I still hadn’t forgiven Matra for the way I’d been treated. It was also special because I had done so much development work on all the Matras, including the 660 that took off and put me in hospital for four months. It was the ultimate accolade for all the work we’d been doing at Matra since 1965.”

Did you relax a little when you saw the times Graham was doing during his first stint?

“You know, when there were only two drivers per car there was never much time to relax between stints. You couldn’t wander too far away in case you were needed. You spent most of your time getting in or out of the car!”

Did you switch every time you refuelled?

“No, we were doing double or triple stints, each lasting a bit less than one hour. But I was keeping an eye on Graham’s progress and immediately felt reassured.”

It’s insane to think you hadn’t talked to each other to discuss the race before you got there. It’s inconceivable today that you wouldn’t practise driver changes, try out different seats, belt settings, head-rest heights…

“No, but you have to remember that the sport wasn’t the same back then. We were all used to jumping into different cars every weekend.

The author Pascal Dro (left) with Pescarolo reminiscing at his home in France

There were a dozen F1 grands prix in the world championship and a similar number of races in the World Sports Car Championship. Matra might not have been doing all the sports car races that season, but most weekends I was just like everybody else, racing in a couple of different events. Switching between cars and changing seats was a matter of routine for all of us. As for Graham, he had confidence in the team. He was quite canny and seemed sure that Matra might be ready to win. That was another reason he wanted to do it! Neither he nor Howden had any problem settling in – but then you tend to adapt quickly when you know you are in a team that’s capable of victory.”

“Back then races were never interrupted, rain or no rain”

After the race, did you shake hands and go your separate ways, or did you remain close?

“Graham and I already had a good relationship, not least because I’d qualified as a licensed pilot at the age of 16 and flying was a common interest. It was my first love and from a young age I’d wanted to be a fighter pilot. It was a bit strange at first, because I’d arrive at the airfield on my moped but was then allowed to take off with four passengers… Going back to the race, I think it would’ve been close between the two leading Matras, if it hadn’t been for Marie-Claude Beaumont’s intervention.”

Even though the other car had been significantly faster in qualifying?

“Graham certainly didn’t set out to take pole – and in my case it was normal procedure to set the car up to last 24 hours. That was the biggest difference between guys like Cevert and Beltoise or Larrousse and I. They would jump in to prove how fast they were, whereas Gérard and I took a longer-term view. I don’t remember even trying to go for pole – I’d just have been preparing the car for the race.”

While 19 drivers since have attempted to equal Graham Hill’s achievement, none as yet has managed to replicate the Triple Crown. The only active drivers to hold two of the three required victories are Fernando Alonso (Indy 500) and Juan Pablo Montoya (Le Mans 24 Hours)

I called Howden Ganley to tell him we’d be having this chat and he told me you hadn’t spoken for years – and that you should call him! He didn’t have the same profile as Graham, so how did he end up with the team?

“Through Jabby, again… As far as he was concerned, French drivers might as well not have existed. And Jean-Luc Lagardère listened to him, unfortunately. But I have to accept that what happened to me was partly my fault.”

How come?

“Lagardère was a great team leader, but he wasn’t much of a psychologist. He never understood that somebody who was shy in life could also be an absolute assassin behind the steering wheel. When Matra needed a replacement for Jackie Stewart in 1968, after his F2 accident at Jarama, Johnny Servoz-Gavin would have taken the lift to the fifth floor, stuck a foot in Lagardère’s door and explained why he was the best choice. Me, I’d have gone up to the fifth floor, waited for the lift door to open… and then pressed the button to go back down! I would never have entered his office to sell myself. In his mind, it wasn’t possible for somebody that shy to be a star driver.”

You won the race again the following season, this time with Gérard Larrousse.

“We won everything in 1973 – Le Mans and the world championship – but I didn’t receive any offers from F1 teams. The best I’d had was at the end of 1971, when Ron Tauranac wanted me to sign for Brabham. Like an idiot I turned him down, because I’d been driving for Frank Williams, who took out his violin and promised me he was hiring a new engineer and so on, but that didn’t work out too well. He next tried the same with Alan Jones, but this time the engineer was Patrick Head! The strange thing was, for Le Mans and other major races, the grid was full of F1 drivers – but there was no promotion in the other direction. F1 was a closed shop and winning endurance races wasn’t going to earn you a better F1 seat. I’d hoped it would, but it didn’t open any doors – and I think the same thing applies today.”