British Racing Partnership: The F1 team whose face didn’t fit

BRP was repeatedly barred entry to the F1 club but its brief existence brought colour to the track, says Gordon Cruickshank

BRP was a trailblazer in F1 with its sponsorship deals but such modernity won it few fans with the establishment

Here’s an honour: in his foreword Bernie Ecclestone says the BRP team “pointed the way for Formula 1”. Quite a compliment from the man who created the modern sport. He’s well placed to comment – he and BRP creator Ken Gregory competed together in F3 in 1951 – and adds that driver management was something else Gregory paved the way for by taking on Stirling Moss.

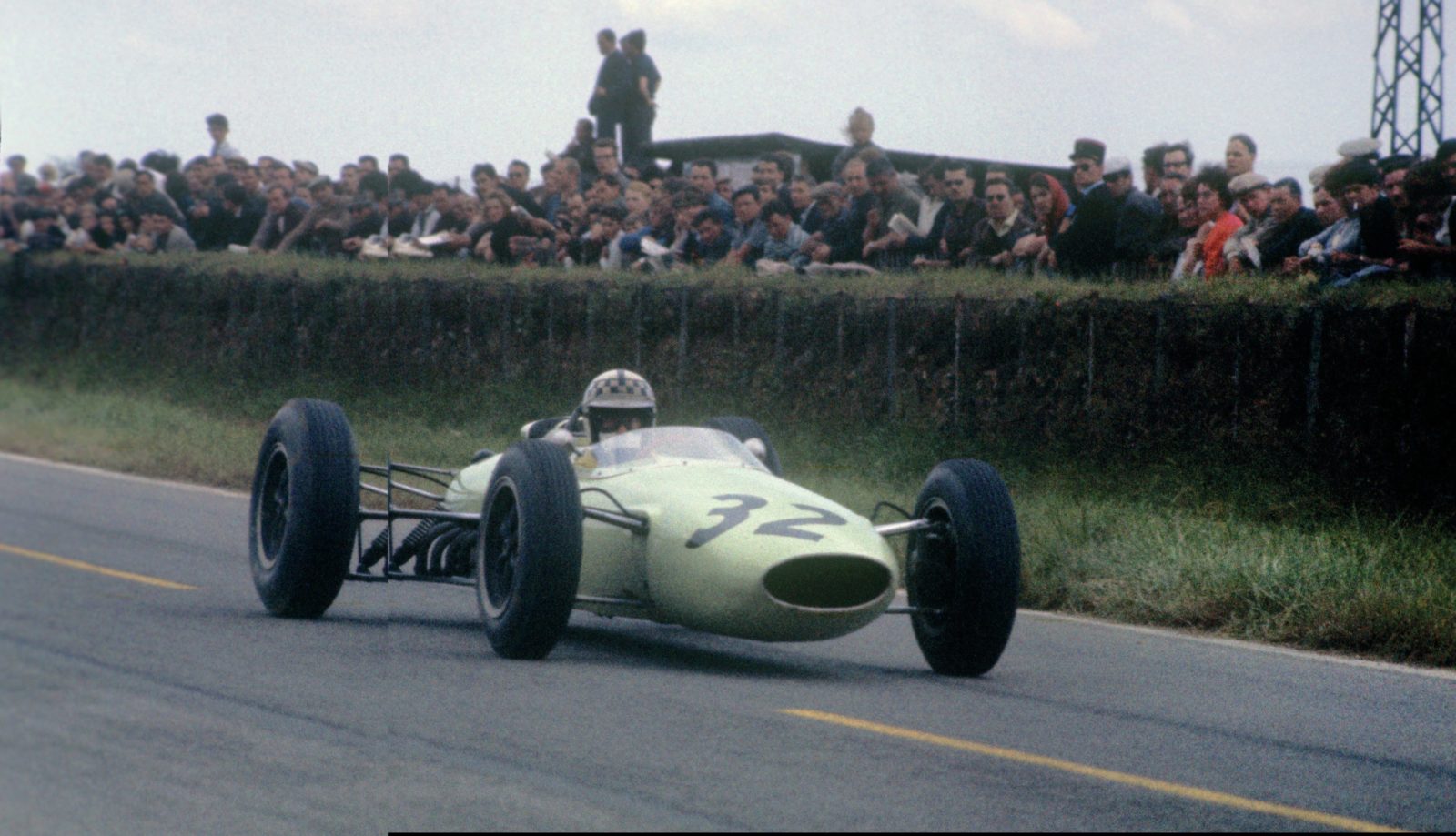

It’s the thread that stitches this enjoyable book together – Gregory’s vision not only in creating this ambitious team but its presentation. One photo colourfully sums that up: four Coopers in matching liveries sparkling in the sun while mechanics in matching pale green overalls polish them. To Gregory, presenting the smartest package was vital to making his privateer outfit an attractive draw for race organisers.

Wagstaff’s involving and informative book, packed with images to drool over, centres on the significance of BRP being the first sponsored race team, though it’s only in a passing comment we learn that it was the Samengo-Turner brothers who first proposed handing over this unheard-of pot of money to the team, not Gregory’s pitch. Nevertheless, in 1958 something called the Yeoman Credit team arrived, pointing the way to John Player Lotus, Marlboro-McLaren and the numerous other headline sponsors.

That Yeoman sponsorship was soon over:

Wagstaff discusses whether it was due to the brothers’ wish to run their own team or was a knock-on effect of the fraud case that innocently involved Gregory. Still, Ken’s supreme networking skills produced another credit company sponsor, UDT Laystall – there’s a sharp Brockbank cartoon of the rival crews holding out pitboards offering different interest rates.

Gregory would hire anyone who was free that weekend, drivers of the calibre of Jo Bonnier, Tony Brooks, or Graham Hill, and sometimes Moss who immediately guaranteed the team entry to any event. For a while the meadow-green cars seemed to be everywhere (“Going pot-hunting” Ken called it), but in fact the team only had six years of life, shortened by establishment resistance and the aftereffects of the deaths of several drivers in BRP machines and later Stirling’s shock careerending smash. But it scored much success with single-seaters and sports cars, though only non-championship F1 wins, and Wagstaff helpfully traces all the car histories.

The product of many years’ work, the book gains from first-hand interviews with those involved – Gregory, with whom Ian worked, Moss, Brooks, the Samengo-Turner family and many others, notably Tony Robinson, the mechanic whose fastidious work matched Gregory’s ambitions.

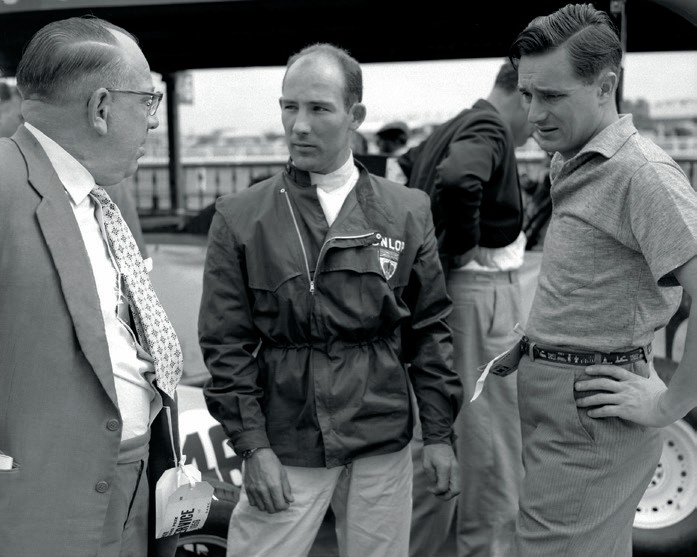

Occasional BRP driver Stirling Moss with team chief Ken Gregory, right at the 1959 British GP

Tony relays Gregory’s mission statement that the cars should be mechanically perfect and spotlessly clean, while drivers and mechanics should be the same. This in an era when any grubby overall would do for most crew. Tony was the perfect complement to thrusting Gregory – thorough, painstaking, could be left on his own to field cars fettled to perfection. And he didn’t like being idle: he recalls a time Stuart Lewis-Evans came in and said everything was “alright”. Robinson replies, “You can’t keep saying everything is alright – please find something wrong!”

If you read Ian’s story in Motor Sport in May [I got the feeling we were being pushed out by the establishment] you’ll know his twinpronged pitch – that BRP has never got the credit it deserved for its innovation, and that the enterprise was snuffed out by F1. He doesn’t shy from pointing a finger at Gregory’s impatient ways either. Motor Sport didn’t help: picking out DSJ’s rude comments about Chris Bristow, he adds: “Chris’s motor trade origins in South London may also have been a factor for Bill Boddy, who perhaps felt that real racing drivers did not come from such backgrounds.”

“For a while the meadow-green cars seemed to be everywhere, but the team only had six years of life”

He’s right – Bill was ever in awe of grander folk. Ian adds that Jenks had little time for Gregory: “To DSJ, mechanics were an essential part of motor sport; team managers were not”.

Wagstaff presents plenty of evidence for both his arguments. BRP embraced innovation, trying pits-to-car radio and the untried Borgward twin-cam engine, and after seeing its Lotus 24s being instantly outdated by Chapman’s revolutionary 25, chose to build its own monococques. This is a team which didn’t even have a drawing office let alone aluminium sheet folders; sections were cut by hand and assembled by their tiny team – “Built rather than designed,” Robinson says.

His proficient designs might have led to great things, and the team’s later own-build Indy machine showed promise, yet that door to the club stayed shut. BRP was rebuffed from joining the F1 Constructors’ Association for “not being manufacturers”. It wasn’t for lack of experience – Robinson laments, “If Innes [Ireland] didn’t bend it, then Trevor [Taylor] did. We built five or six frames that year.”

Still, its application was repeatedly refused, starving it of essential funds. Ian can’t prove whether it was the team’s ‘downmarket’ aim of making money out of motor racing, a dismissive press attitude, Gregory’s edginess or what he called “fear” of its achievements – though is it plausible that BRM, Lotus, Cooper and Brabham ‘feared’ this little outfit?

Yet this was a team with the clout to obtain a new GTO from Ferrari, win the TT and be offered a Sharknose to run for Moss. In Ian’s story in May he says of Gregory’s anger and disappointment that “perhaps hubris got the better of him”. But isn’t fulfilling what might early on look like hubris exactly what got McLaren, Williams and Ferrari to their goals?

|

Formula 1’s Unsung Pioneers Ian Wagstaff Evro Publishing, £95 ISBN 9781910505724 |