Reviving Pegasus racing: Getting the band back together

A major player in the junior single-seater scene, the first iteration of Pegasus was wound up in 1986. Now the name has made a return through historic racing, with the distinguished Trevor Foster once again at the helm. Damien Smith spoke to him

Pegasus is ready to fly again, for the first time since 1986. At 70, Formula 1 veteran Trevor Foster has every right to put his feet up after a half century in the pitlane. But you know what’s coming… he just can’t leave it alone. Instead of the pipe and slippers, Foster has revived Pegasus, the team he ran back in the 1980s in Formula Ford and Formula 3 when he fielded the likes of Andrew Gilbert-Scott, Gerrit van Kouwen and Graham de Zille.

Except this time he’s steering well clear of the stormy cut-and-thrust of what are now one-make single-seaters, choosing instead to launch Pegasus into the clear blue skies of the booming historic racing scene. Call it a labour of love.

Pegasus driver Gerrit van Kouwen racing in British Formula 3, 1985

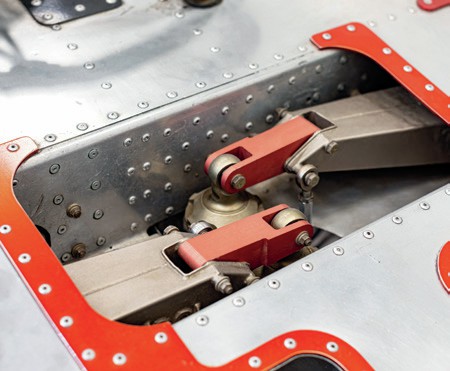

Motor Sport arrives at a brand new unit on an industrial estate tucked against the M1 in Lutterworth, Leicestershire. This was an empty shell a few weeks earlier, but Foster and his hand-picked crew have fitted an office and mezzanine, while the jewels are already in situ: a pair of stripped Sports 2000s and a trio of stone-cold classics – Lola T70 MkIIIB, Chevron B16 and Lotus Elan 26R.

The cars belong to another racing veteran, Ross Hyett, who has entrusted his gems to a man with a remarkable track record: F1 years with Shadow, Tyrrell and most famously Jordan, plus decent stints in sports car racing with Zytek and recently United Autosports, heading up its LMP2-blitzing campaigns at Le Mans and beyond. Fair to say, he’s a safe pair of hands.

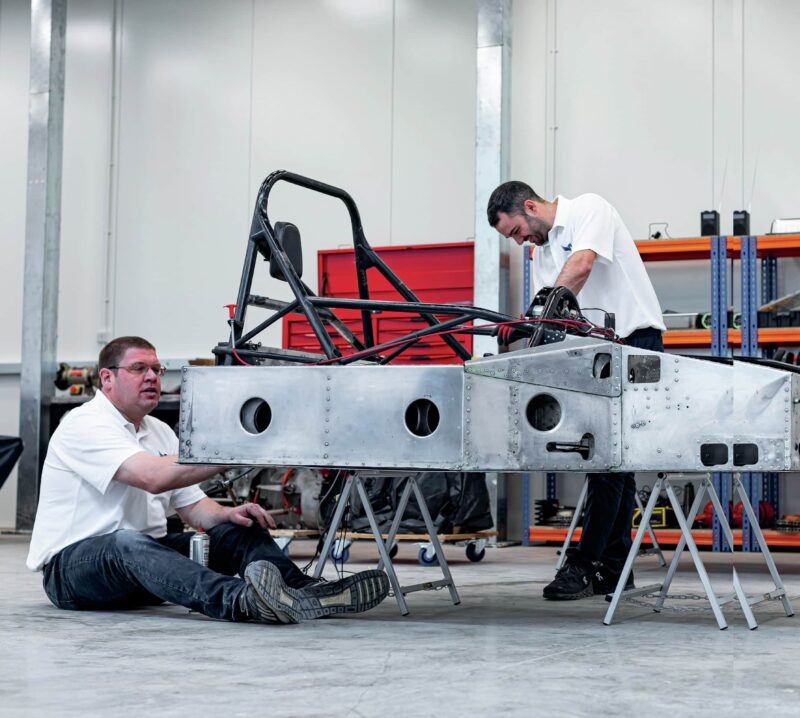

Pegasus crew Chris Phillips, left, and Adam Dunnan at work on a Sports 2000. The company is ready to fly in historic racing

“It was time,” says Foster of his mindset last autumn when he left United to revive Pegasus on his own terms. Richard Dean recruited Trevor in 2016 as United expanded into LMP2. From the European Le Mans Series, the programme grew into a title winning World Endurance Championship success story that included a gleaming class victory at Le Mans in 2020. “I’d done five years, but I’d become more of a manager,” says Foster, who still prefers a hands-on approach to racing engineering. “I live in Loughborough and was travelling up and down to Leeds every day. The pendulum had swung: ‘is this really what I should be doing? What do I do?’ I didn’t want the challenge of looking for another race team. I had contacts in the classics world, so what if I take the plunge and start my own little thing?”

Pegasus Classic Engineering will likely soar on the high-value currency of Foster’s vast experience. He still loves working with racing drivers. Which begs the question, who specifically left the biggest imprint, first as mechanic and then as engineer? The span, across five decades, represents the touch points of a remarkable life in racing.

“I didn’t want the challenge of looking for another race team”

Running cars on the historic scene is a world away from Foster’s traditional roots in Formula 1, junior single-seaters and cutting-edge Le Mans prototypes. But consultancy work for Silverstone Auctions – during which he helped to verify whether cars were in fact what their owners claimed they were before they went across the block – sowed the seed for the revival of the Pegasus racing operation.

Foster is once more helping both drivers and cars improve their performance

“I didn’t want to run a modern racing team, having to find the drivers and be always looking for a budget, because that’s not for me,” he says. “I’d much rather concentrate on sourcing cars for people, restoring them, then taking them to races and events. These are relatively basic cars we’re talking about, and you can break them.

Modern cars have systems to stop you doing things like that: the whole ‘computer says no…’ thing. These historic race cars don’t have any of that.

“I’ve always enjoyed making progress in whatever part of the sport I’m in, whether that’s making a particular car faster or making an individual driver perform better.

Now I can pass on some of the knowledge I’ve learnt in a very fortunate career.”

Now Trevor Foster is in the corner of driver Ross Hyett. He’s lucky to have him.

Roger Williamson

Poorly-equipped camping at Mallory Park motorcycle races was where the bug first bit for Trevor Foster. Following school, he worked on road cars by day, Mini race cars by night, before getting his (part-time) break with Bob Gerard in Formula 2 and Atlantic. “Then in 1973 Roger Williamson had just won the F3 title and was going to F2,” says Foster. “He needed another mechanic. Roger was a phenomenal driver. He was just so hungry – and talented.

He would do all sorts to get to races because he didn’t have unlimited funding and was very fortunate to have a good backer in Tom Wheatcroft, who treated him like a son. They had a phenomenal relationship, but Roger never took it for granted. He was always so grateful. Tom would say, ‘Let’s buy a spare engine,’ and Roger would reply, ‘We can manage.’ ‘No lad, you’re having a spare engine.’

“We struggled because he had a GRD to start with because he’d won F3 in one. Then Roger had a brake failure at Nivelles in Belgium and it badly damaged the car. Tom said, ‘That’s it, I’m finished with this. I’ve just had a coffee with Max Mosley and I’ve bought a March.’ We had a BMW engine, the thing to have, went to Rouen and the grid was so big it was two heats and a final. Roger was in one heat, very quick, just pushing on. We were leading and he had a problem, lost oil pressure. I have these visions of Roger: it was the meeting where Gerry Birrell was killed and all the drivers were saying it’s too fast down the hill. Eventually they put straw-bale chicanes in. It sounds like he was blasé, he wasn’t – but Roger’s view was if you think it’s too fast don’t press the throttle as hard. He knew the risks. Part of it is being able to conquer that fear. He was not reckless, but this part of the track was the challenge for him.”

Foster has happy memories of travelling across Europe with Williamson and his F2 March, before Wheatcroft broke some news.

“He had this opportunity for Roger to run in the works March in F1. He did the ‘73 British GP at Silverstone and got caught up in the Woodcote pile-up, through no fault of his own. Then there was the Zandvoort race and the question was, could they get the car ready?

It needed a new tub. Also the corresponding weekend there was an F2 double-header in Sweden. Tom said, ‘We’ll prep the F2 car, you guys take it to Zandvoort. Stay there and we’ll make a decision on Tuesday or Wednesday. If they can’t get the car ready trundle off to Sweden and we’ll do both F2 races. If not, you can spectate at Zandvoort, then we can go off to Sweden and do the second F2 race. That meant we were there when the accident happened.”

The TV pictures of Roger Williamson’s tragic accident at Zandvoort showed the sport at its worst. Foster shared in the trauma, yet like so many before and since felt compelled to press on

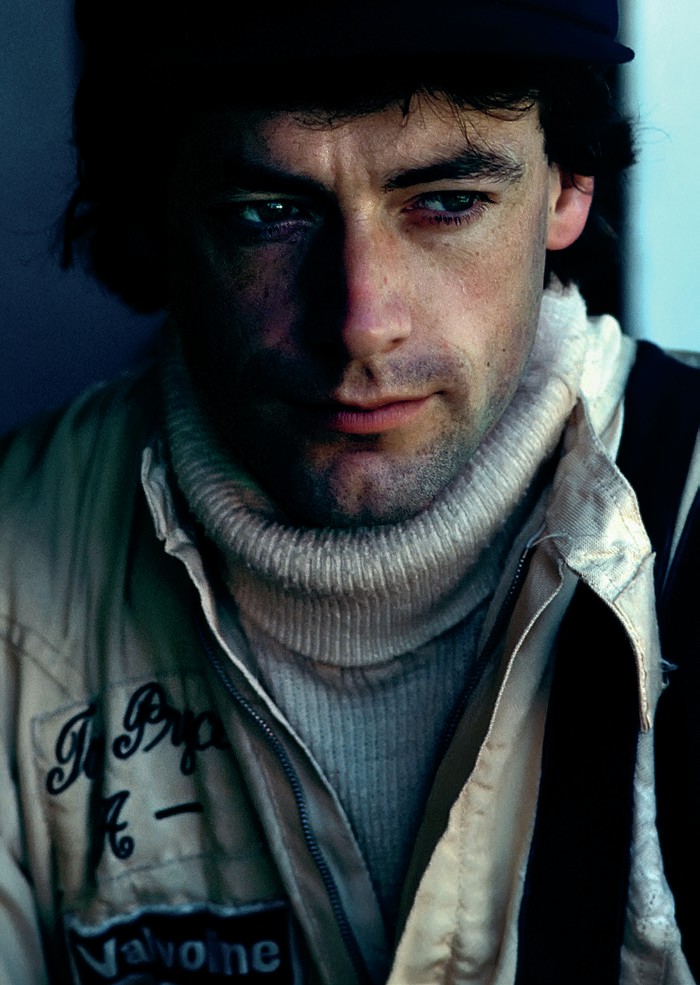

Tom Pryce

Without clear ambition Trevor landed in F1, via Shadow. “The first day I turned up they told me to head to the post office to get a provisional HGV1 licence because, as the new junior mechanic, I was also trucky’s mate.

I believe we were the first to have an artic – before Brabham. It was a great experience.”

Mentored by Kiwi Pete Kerr, Foster learnt fast. “Yes, the cars were more simple back then, but you did everything,” he says. “You serviced the uprights, the chassis work, rebuilt the gearbox, you were a damper technician. It’s far more specialised today.

“Tom Pryce impressed me massively.

Highly skilled, phenomenal car control, loved driving sideways – sometimes too much for ultimate speed. But he was spectacular to watch. Very quiet and unassuming.”

Foster had moved to Tyrrell by the time Pryce died at Kyalami in 1977, when his Shadow collided with a marshal crossing the track carrying a fire extinguisher. “We didn’t know until after the race. What a shock.”

Quiet and unassuming out of the car, flamboyant and fast in it. Tom Pryce was a huge loss to the sport

Andrew Gilbert-Scott

A gear change or two next, as Foster left Tyrrell for March where he was chief mechanic for the works F2 team in 1979, running Markus Höttinger (killed a year later at Hockenheim, an unfortunate running theme for Trevor in his first racing decade). Then he enjoyed a spell rebuilding and restoring classic Ferraris, until in October 1982 he formed Pegasus.

Steered by Andrew Gilbert-Scott, the team and its Lolas scooped the full set in 1983 FF1600: RAC and Townsend Thoresen titles, the Festival at Brands Hatch with a Reynard, plus with Graham de Zille the BP Superfind crown. How Gilbert-Scott never made it to F1 after such obvious early promise remains a motor sport oddity.

“He came to it quite late, but was so talented and calm under pressure,” says Foster. “He just got out there and did the job.

One weekend, we did a doubleheader across Silverstone and Brands Hatch. We found a bit of sponsorship to hire a small light aircraft to go between. We qualified at Silverstone, left a mechanic there and shot off without knowing what position we were in, got in the plane and flew to Biggin Hill where there was someone to take us to Brands. We did qualifying there, again left without knowing where we’d qualified and flew back up to Silverstone. The mechanic had the car in the assembly area, Andrew jumped in and it turned out we were on pole. He won the race, we then flew back down to Brands and won the race there from pole! Andrew’s girlfriend stayed at one of the tracks to give us information on where we were, but of course there were no mobile phones then. He was just so calm through the whole thing, and he was a good influence on me in that regard.

Gilbert-Scott lets it all hang out after switching to a Reynard for the 1983 Formula Ford Festival

“Andrew was going on 21 and felt he should already be in F3. Our sponsor was ready to step up to Formula Ford 2000, but

Andrew was desperate to do F3. Eventually he went to F3, did three races, ran out of money and his career stuttered. You need that momentum, even now. Whatever you do you have to win and if you are stagnant for a year or two suddenly there’s a new champion with the momentum. Andrew got himself out of kilter in that regard. And he could never go to the best possible team because he didn’t have the budget. He went to Japan, had a career out there and made good contacts. I did get him to test the Jordan a few times during shakedowns.”

Johnny Herbert

A year later he was in the F1 pit in Benetton colours

Pegasus ran out of puff, Foster clipping its wings by the spring of 1986, whereupon he took off once more with the Swallow F3 team.

Then Eddie Jordan came calling as he planned his graduation to F3000, Foster finally working with a driver he’d wanted to hire during the Pegasus days. “I’m a big fan of Johnny,” he says. “I was then and still am.”

As chief race engineer at Eddie Jordan Racing, Foster would work with Jean Alesi, Martin Donnelly and Eddie Irvine – but it’s Herbert in 1988 that stands out. “Johnny was fantastic, as good as the best I’ve seen, before and since,” he says. “Like Andrew, he was very relaxed, didn’t blame the car and was a joy to work with. We won the first race in Jerez, but it was a new car and we were still learning about it. He was getting stronger every race that year and we were just getting the Reynard to his liking when we got to Brands Hatch.”

Herbert remains stoically accepting of the sliding-doors ‘what if’ that surrounds the ankle-mangling crash with Gregor Foitek that changed his destiny in August 1988. Like everyone, Foster was amazed by his fourthplace F1 debut for Benetton in Rio eight months later, then shared the frustration when Herbert’s injuries “caught up with him”, Flavio Briatore replacing Johnny with Emanuele Pirro mid-season. “He’d spent months doing physio, which was helping, but once the season started he deteriorated in his mobility,” says Trevor. “He couldn’t do all the physio and the races as well. I talked to him years later about how the injuries affected him. He said, ‘When I drove in F3 and F3000, people talked about feeling the car through your backside. I felt it through the pedals.’ His left foot is welded at a right angle and he’d lost that bit of his feet talking to him. But he didn’t blame anybody. Yes, I know he went on to win Le Mans and some grands prix, but what would he have won? A lot more, I have no doubt.”

Jordan’s Johnny Herbert, No31, at Silverstone in ’88, battling Jean Alesi in F3000.

Michael Schumacher

Foster was at the heart of Jordan’s celebrated first F1 season in 1991 and, while his experience of working with Michael Schumacher lasted all of one weekend, and a matter of a few hundred yards in the Belgian Grand Prix itself before the 191’s clutch broke, inevitably the young version of the future seven-time champion left a deep imprint. Foster picks up the story when Bertrand Gachot found himself ‘indisposed’ following his altercation with a London cabbie. “Myself, Gary [Anderson, chief designer] and Eddie talked about who we should put in. One idea was Keke Rosberg, who had conversations with Eddie about coming back. Gary and I agreed bringing in a guy who had been at Williams into a small team like us would be a burden, in terms of what he would expect. We knew Michael a little bit. Although he could speak English I don’t think he was 100% confident about using it. We’d been talking to [his manager] Willi Weber the previous year about selling off the F3000 team to him, so we’d seen him at a few races and he’d brought Michael around. A few people were trying to push Heinz-Harald Frentzen at the time: ‘if you’re going to take a Mercedes Group C junior you want Frentzen, not Schumacher’. But eventually the decision was made.

Michael Schumacher, Jordan-Ford 191, Grand Prix of Belgium, Spa Francorchamps, 25 August 1991.

“He came to Silverstone for a seat fit and we arranged a run-out on the South circuit.

In those days you had no down-change protection, an H-pattern gearbox and every time you buzzed an engine over 13,500rpm, which was very easy to do on the downshift, it was a £30,000 bill from Cosworth – and budget-wise we were struggling. I think it was the Monday or Tuesday ahead of Spa.

The truck left and we stayed on with a van and trailer, believe it or not, with Michael’s race car. We got him in and I was saying to him, ‘This is the race engine, it’s got to do all weekend.’ But literally within five laps he was just like he’d always been in it. The carbon brakes were glowing, he was flicking it through the corners, nothing was a drama.

He instantly went quicker round the South circuit than we’d ever been before and I had to say to Willi, ‘I’m going to have to bring him in.’ I was trying to measure his expectations, explaining we didn’t have a huge amount of spares. I had to say it to Willi, who then translated to Michael. I said, ‘Is he OK with that?’ ‘Yes, but he doesn’t really understand the problem.’ It just came to him.

Michael Schumacher’s debut grand prix weekend may not have ended as planned, but he made a huge impression

“At Spa he was so impressive: not just how he drove, but how professional he was.

Even though it was his local track, he’d never been around Spa. But having cycled it on a fold-up bike, straight away in FP1 he was on the money, but very calm. When he came in I said, ‘Michael, it is going really well, but you don’t need to drive over the limit or take big risks for your first grand prix.’ He said, ‘No, no, I’m not over the limit, I’m on the limit.’ As calm as that.”

Filipe Albuquerque

Apart from a brief spell at Team Lotus, Foster remained intrinsic to the Jordan story until 2001 when he’d finally had his fill of Eddie… (see right). Following a year of consultancy at BAR, he spent eight years as managing director of Zytek, overseeing the engine specialist’s expansion as an LMP constructor and race team, then remained active as an engineer for hire until Richard Dean snapped him up full-time for United in 2016. There, he worked with Paul di Resta, plus Fernando Alonso and Lando Norris when they joined the team for the Daytona 24 Hours in 2018.

But it’s a largely unheralded driver that left the greatest impression from that time.

At 36, Portuguese Filipe Albuquerque has been around a long time, gaining vast experience during a slow-burn career that still has some miles left to run. A key part of United’s LMP2 Le Mans win in 2020 and briefly an Audi LMP1 factory driver before the marque pulled out in 2016, he’s twice an overall winner of the Daytona 24 Hours. “He was such a good influence on the team, with the younger drivers,” says Foster. “He comes across as very happy-go-lucky and clowns around a bit, but fundamentally when the job needs doing he’s there. It’s a bit of a mirage as underneath there’s a burning ambition.

He’s had some hard times and he’s had to work hard for where he’s now got to.”