From Monaco to Indy: Race against time

Witnessing the Monaco Grand Prix and Indy 500 on back-to-back weekends is a sports fan’s dream. Chris Medland grabs his passport for a transatlantic odyssey

On May 15, 1977, Clay Regazzoni crashed heavily after spinning to the inside of the track out of Turn 3 at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and his hopes of qualifying for the Indy 500 were left in the balance.

Racing in Monaco the next weekend, Regazzoni had needed to secure his spot on the grid at the Speedway at the first time of asking. Now he’d need to do the same in Monaco qualifying on the Thursday, return to Indianapolis for another attempt on the Saturday, and then fly back again to Monte Carlo to race the following day.

After a rain-affected practice session on Thursday left him outside the top 20 required to make the Monaco grid, Regazzoni’s plans were looking risky. With grey weather on Saturday morning threatening to make an improvement impossible, the Swiss driver made the decision to head back to the Brickyard to get into the 500, giving up his chance of racing in the Principality.

He made it into the show in the States, but would then only run 25 of the 200 laps in the race itself the following weekend before suffering a fuel leak.

Things initially went more smoothly for his F1 compatriot Mario Andretti. After clocking an average of 193.353mph on a four-lap run in his Penske McLaren during the first day of qualifying at Indy – good enough for a place on row two – he flew to Monaco, qualified his Lotus 10th and finished a career-best fifth.

Starting two of the three races that make up motor sport’s Triple Crown in successive weekends, he too then faced the return trip across the Atlantic to Indianapolis. But it wasn’t quite the brutal travel schedule you’d think.

Aided by favourable time differences and supersonic flight technology, Concorde was the key to unlocking the Monaco and Indy pairing in the 1970s

“Quite honestly the beautiful thing about the travel back and forth in the ’70s especially was the Concorde,” the 1978 F1 world champion says. “In my title season I did 24 crossings on Concorde in one year alone. I owned the damn thing!

“Monaco and Indy wasn’t too hard at all, especially as you land earlier than when you’d left using Concorde. I remember later in ’77 I won the French Grand Prix in Dijon and then I got a helicopter ride with [Cosworth engineer] Keith Duckworth who dropped me off at Le Bourget. I got the 5.45pm Concorde to New York, my plane picked me up at New York, dropped me off at my lake property in the Pocono Mountains and the race was broadcast on a delay by CBS so I arrived there 10 minutes before the race was over!”

“If you have to choose one race in your life, you choose Monaco”

The travel was a breeze, but on track Andretti’s Monaco-Indy pairing that year was less successful. From Monaco he headed back for the 500 the following weekend, but his race only lasted 22 more laps than Regazzoni’s.

Both drivers were helped by a schedule that saw Indy 500 qualifying taking place the week before the Monaco Grand Prix, while there was a final chance to get in on the weekend of the F1 race and then the 500 itself was held a week later.

These days, it’s rare that there’s no clash. Even back then, drivers often had to choose between the two: “Monaco was really important for me; I wasn’t going to miss Monaco for Indy,” Andretti says of his 1979 decision, and he remains the last driver to attempt both races in the same year, some 40 years ago.

“It was amazing how good the travel was,” he adds. “We’ll never see that kind of thing again. Today it is so much more complicated, when it should be the other way around.”

Travel in style: a group including Lola’s Eric Broadley, Jackie Stewart and Graham Hill enjoy an airborne drink heading to the 1966 Indy 500

Harry Benson/Express/Getty Images

Complicated or not, this year race day at Monaco and Indianapolis fell on separate weekends for the first time since 2010. And on that occasion, there was still an F1 race in Turkey, so it has been 18 years since Indy even had the race weekend to itself.

There might not have been a driver able to attempt both thanks to the timing of qualifying for the 500, and as Andretti had pointed out travelling was hard enough prior to the pandemic, but it was an opportunity I couldn’t miss.

Mario Andretti was the last driver to contest both Monaco and Indy in the same year, back in 1979

Bernard Cahier/Getty Images

First up is what is now a familiar trip to Monaco for me, although one which this year required a lot of literature and curfew exemptions just to get to and from the event.

But unlike almost all of the other grands prix in the past 18 months, that hassle is totally worth it. Stepping into the Principality after two years away feels comfortingly familiar, and with up to 7500 fans per day permitted – 40% of capacity – there’s a hint of the usual buzz that comes with the race, too.

“It’s the race that we all want to win,” reiterates Fernando Alonso, who has returned to Monaco after two further cracks at the 500 since his first in 2017. “If you have to choose one race in your life, you will choose Monaco. And you choose Monaco because it’s part of Formula 1 history.

“I think it’s the most iconic weekend, the most glamorous one, the Cannes Festival and actors – everything is happening in Monaco. And you have this place in the middle of the city that the race is actually not very attractive because it’s normally quite boring after qualifying, but there is something special about this place. It has been in F1 a long time and it is iconic, and you want to win here.”

At 50% capacity, 7500 fans were allowed to attend Monte Carlo this year, bringing back some of the race’s special atmosphere

But thanks to Covid-19, this year is the PG version of Monaco. An 11pm curfew means bars are closing early, and there’s none of the late-night partying or the major events that usually come hand-in-hand with the race.

“F1 as a business looks at what goes on in Indy and sees lessons it can learn”

Local fans are still passionate – the lady giving me my PCR test on Sunday morning is an avid Charles Leclerc fan and a bag of nerves after the crash that secured him pole (rightly it turns out) – but their way of showing it is very understated. Qualifying is special, but Monaco shouts through the razzmatazz that surrounds the race, and that is heavily watered down.

“Honestly the show is incomparable,” Alonso says, prepping me for my first 500. “I think the show is unfortunately nearly zero in Monaco on Sunday, and it’s 100 on Sunday in Indianapolis. It’s so much fun. There are so many more opportunities to overtake – constantly overtaking – much more drama, the pit stops, the yellow flags, the uncertainty of who is going to win…

“While in Monaco it’s guaranteed that the first two or three cars will win the race, in Indianapolis the 28th car can win the race, and this is probably the two sides of motor sport in a way. So it’s quite funny that two of the most prestigious races in motor sport are so apart in terms of the racing show.”

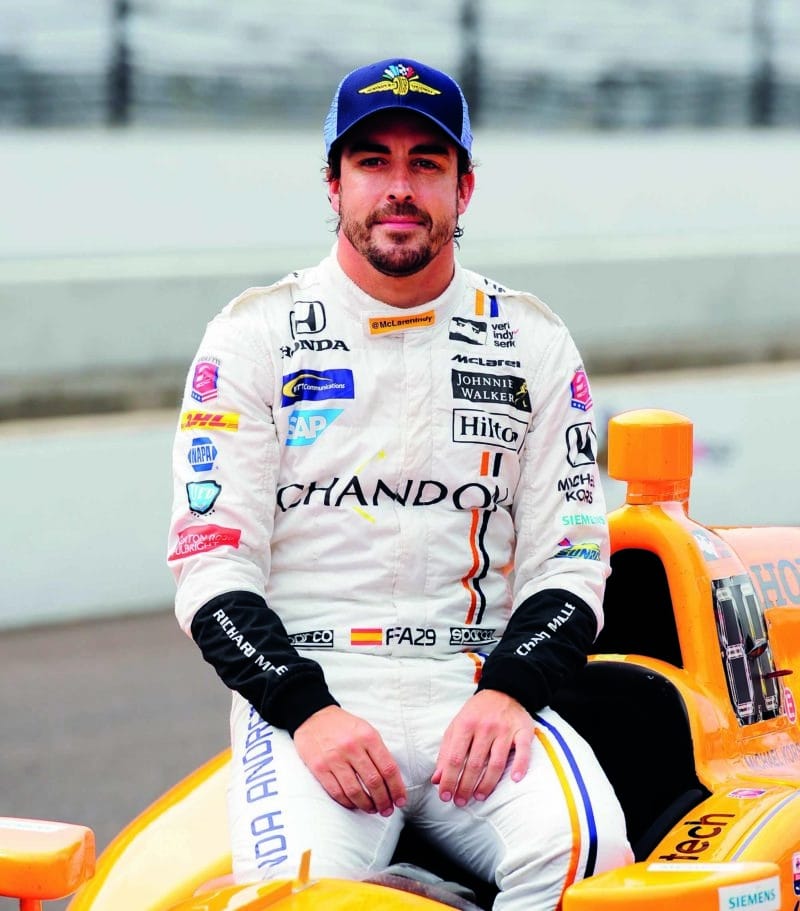

Fernando Alonso had to choose between the Monaco GP and Indy 500 in 2017

I’d covered Alonso’s first two attempts to qualify for the 500 in person but not been able to stay for the race on each occasion, so I’m like a kid at Christmas when I travel back to London on Sunday night (straight into self-isolation) before a planned flight on Wednesday morning. But the US Embassy has other ideas and doesn’t issue my travel exemption until Thursday morning, leaving me with a hastily-rearranged Friday trip to Chicago and dash down I-65 to the Speedway.

It’s eerily quiet on arrival. Carb Day running has already finished, so all I can do is head to a McLaren event under the pit grandstand. Here, a 1972 Ford Condor II is the centrepiece of a happy hour event where drivers mix with media, as Juan Pablo Montoya hangs out under the awning of the original McLaren Can-Am hospitality vehicle.

In Indiana, a ‘meagre’ 135,000 fans were allowed into the Brickyard, where emotions ran high after a fourth win for Hélio Castroneves

Montoya is one of seven ex-F1 drivers starting this year’s race – along with Marcus Ericsson, Alexander Rossi, Pietro Fittipaldi, Takuma Sato, Sébastien Bourdais and Max Chilton – of whom five have raced at Monaco.

From his RV parked on the infield, Chilton describes the IndyCar season as travelling around the country to promote the 500, and Ericsson backs up its magnitude – despite never having race-winning machinery in F1 – with an unequivocal answer when I ask which of the two iconic races he’d rather win.

“The 500,” the Swede insists. “I never would have said that before I came and raced here, but there’s something about it. Racing so close to each other at 230mph for over three hours – you can’t describe it. Now I believe it’s the biggest race in the world. All the guys that have been here for a long time would pick the 500 over the championship. I’m still struggling to make that call, but when you hear them say that you feel the same.”

Ericsson and Alonso look at it from a racer’s perspective, and clearly the lower dependency on your machinery makes the 500 attractive. But F1 as a company also looks at Indy and sees lessons it can learn, specifically surrounding the build-up.

“Indy 500 is almost like the Super Bowl,” F1’s Ross Brawn says. “It’s a whole big event for the whole weekend and that’s definitely something we take from it. We’re encouraging our promoters to build a lot around the event in terms of support events, music festivals, exhibitions, demonstrations – build the whole week up into a great event. I think that’s something that they [Indy] do very well.”

Medland interviews Fernando Alonso at the Monaco GP before making his dash to the Brickyard

Made it! Medland soaks up the atmosphere Stateside after a torrid journey across the Atlantic

In Andretti’s day, being able to return so quickly from Monaco meant being a part of that whole week preparing for the race, but I arrived less than 48 hours before the green flag. On race day I arrive at the track at 6am as a cannon goes off and fireworks light the stilldark sky over the Speedway to signal the gates being open, because this might be a race also operating at just 40% capacity, but 135,000 people still makes for a lot of traffic.

Some fans are instantly in their seats for sunrise, having – like Monaco – been starved of attending last year. By 7am they’re swarming the plaza behind the Pagoda. Then comes cars being pushed into the pitlane, the Borg Warner Trophy appearing, and drivers walking through a sparsely-populated Gasoline Alley.

It’s at this point I really notice the place isn’t full: 135,000 looks like a lot in the grandstands, but the noise isn’t crazy as the drivers are presented in trios, row-by-row. That said, I can’t help appreciate the choreography as the pre-race ceremonies slowly build to a crescendo after the national anthem, with Roger Penske himself shouting those famous words: “Drivers, start your engines!”

It’s a relatively tame start, as Scott Dixon – ominously quick in practice after taking pole – drops back behind Rinus Veekay and Colton Herta to save fuel in their slipstream. But when a badly timed yellow closes the pitlane with Dixon about to run out, he’s eliminated from contention and the race is wide open.

Still the crowd waits. They know it will get better yet. Developments in the first 50 laps warrant little response, until home favourite Conor Daly hits the lead and the noise grows.

Standing behind Pato O’Ward’s pitbox, the tension increases. “It’s just pitstop practice, man,” one mechanic reassures another. As the strategies play out, O’Ward’s right in the mix, leading a number of laps and then tucked in behind Alex Palou and Helio Castroneves for the final stint.

Palou has supporters, as a woman in a ‘Back Home Again’ vest screams in delight as he takes the lead, but it feels like the other 134,999 erupt as Castroneves sweeps by with two laps to go and secures an historic fourth success. The 46-year-old climbs onto the fence to celebrate with the biggest sporting crowd since the pandemic, and it responds with a deafening chant of “Hé-li-o! Hé-li-o! Hé-li-o!”

I can’t help but well up a little with joy at the scenes, and that’s when Alonso’s comments ring even more true. It’s just as important to win as Monaco, but the show is incomparable, both on and off the track. It’s all about the fans, and even with ‘only’ 135,000 of them, Indy is quite simply the biggest race in the world.

That’s why Regazzoni and Andretti would fly forever to be there, and the latter admits: “With Colin [Chapman], every contract I had, had a clause that forbid me from doing anything else. And I never argued that point because I was going to do it anyway.”

Even without Concorde these days, I think I might just need to take a leaf out of Mario’s book next May.