F1 rear wing designs: Feeling the force

Baku’s unique layout gave teams a number of rear wing options, each giving very different results

Red Bull opted for low-downforce setups to maximise top speed

The rear wing choice at Baku is much more complicated than usual because of the track’s combination of extreme low- and high-downforce sectors. This year brought an extra dimension for Red Bull, as this was the last race before the FIA’s new protocol for measuring wing flexibility came into effect and there was the threat of Mercedes protest in the air.

The new protocol followed complaints from Mercedes that in the Spanish GP the Red Bull wing could be seen flexing downwards and back at speed on the straight, thereby reducing drag but still giving full downforce as it came back up at the lower speeds of the corners.

From the French GP on-board camera analysis would be used, together with 12 key markings teams would be obliged to make to specified parts of the wing to aid detecting any flex. The FIA would also reserve the right to test at 1.5 times the regulation load (currently 1000 Newtons, with no more than 1 degree of flex allowed) to measure any non-linear behaviour. The wings invariably see more load at high speed (up to 4 tonnes) than can be replicated by the FIA’s static load test, hence the motivation for that non-linear flexing behaviour once past the regulation load threshold. For the first month of the new protocol, a 20% tolerance will be granted.

Red Bull turned up at Baku with two new rear wings, both expected to feature some degree of flex. Camera analysis confirmed as much. But while at Barcelona the Red Bull wing could be seen flexing considerably more than that of the Mercedes, in Baku the two were displaying very similar levels of height reduction at speed. The threat of protest receded.

What’s in a wing?

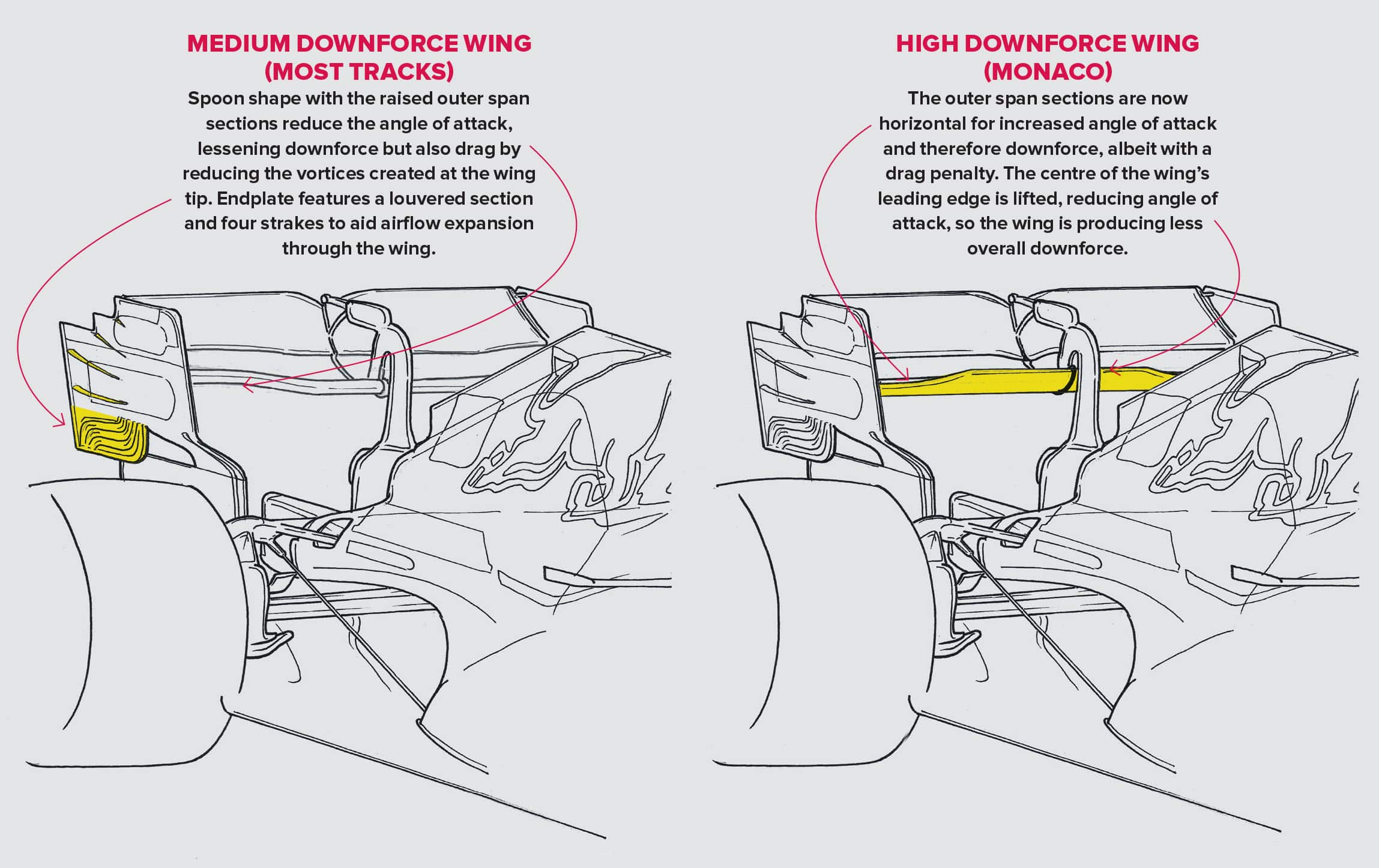

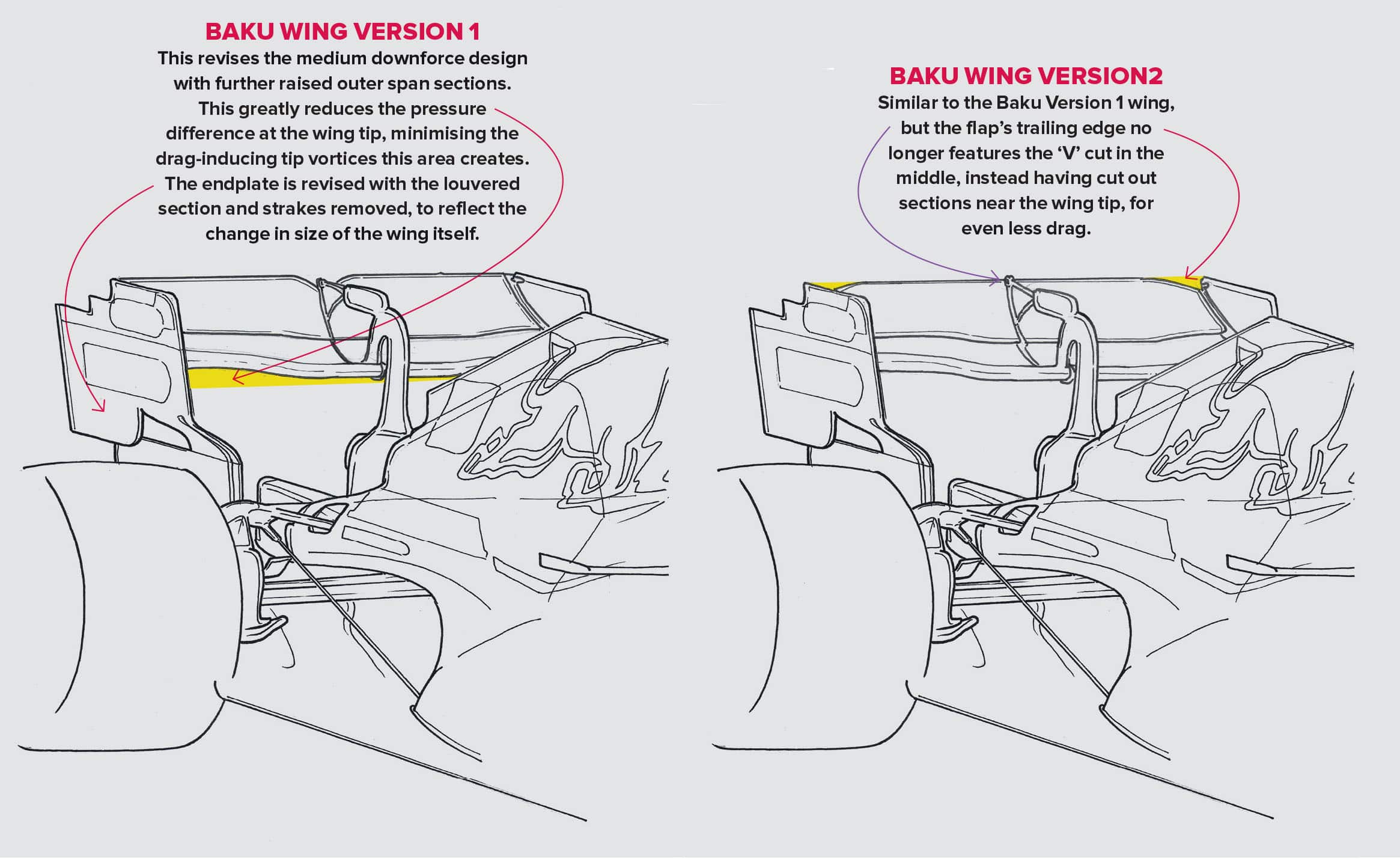

Many teams opted to run two different rear wing assemblies for Baku, one to generate high downforce, and one to lessen drag on the long straights. The mixture across the grid was fascinating. Here’s how the shapes change to create each effect

Illustration Craig Scarborough

Mercedes and Ferrari also had a choice of rear wings, but the choices for each of the three teams were quite different. Red Bull had made two specific Baku wings, both featuring a ‘spoon’ profile with cutaways at the outboard ends. The lower-downforce version was cut away at both the mainplane and the flap above. The higher-downforce version had a conventional flap but spoon main plane.

Mercedes’ wings, not Baku-specific, were conventional in profile with just a choice of higher or lower main plane and flap area. Lewis Hamilton used the lower downforce one from qualifying on while Valtteri Bottas kept the higher-downforce version, further visually distinguishable by its twin mounting pillars.

Ferrari, down on power to the others, had a choice of low or very low downforce, the former with a spoon-shaped lower main plane, the latter just a tiny main plane area, shallower across its whole width than even the outboard ends of the spoon version.

“This year’s Mercedes is prone to not warming its tyres fast enough”

The ‘spoon’ profile is a popular Baku compromise. Because of the unusual conflicting mix of Monza-Monaco sectors, both low and medium downforce are feasible options. The full-on low-downforce option (as used by Ferrari and Hamilton) can produce you a lap time, but usually at the expense of heavy rear tyre graining. By contrast, the spoon profile allows a good downforce-producing surface in the middle of the wing, but cuts away the least efficient parts, the outboard ends where different airflows converge, inducing drag.

In addition, the endplates of both Red Bull wings were flat when viewed from head-on, as opposed to the standard endplate which features downforce-enhancing slots and vanes. This too was in the interests of drag reduction.

In the past Red Bull opted for a low-downforce setup at Baku due to its mix of less power and high drag. But that very often left the team with tyre difficulties, the surface of the rears tending to overheat while the core stayed cool (hence the graining) through repeated sliding in the old town section. But Red Bull is no longer under-powered, so it wasn’t going to be forced down that route.

Mercedes historically has always favoured a relatively high-downforce wing here. This year’s car is especially prone to not warming its tyres quickly enough, a trait which has lost it races in ’21 just as surely as its better control at the upper end of the temperature spectrum has won races. Extra downforce is a good way to get reluctant tyres to switch on, working the core harder, bringing it up to temperature more effectively and thereby putting less strain on the tread surface and reducing the graining risk.

Hence Mercedes was naturally expected to err towards more downforce. But the practices showed that even with the higher downforce wing the tyres were still not properly warming as this street track just doesn’t impart much energy into the tyres, either through its surface or its corners. Hamilton therefore decided to go low downforce for qualifying and race, to at least take the straight-line speed benefit.

In order of downforce (and drag) production, the order of these six wings was probably:

1. Mercedes higher downforce – Bottas

2. Red Bull higher downforce – both drivers

3. Red Bull lower downforce – not used

4. Ferrari higher downforce – used only in practice

5. Mercedes lower downforce – Hamilton

6. Ferrari lower downforce – both drivers