The hard chargers

Baku was as much about tyres as wing angles, says Mark Hughes

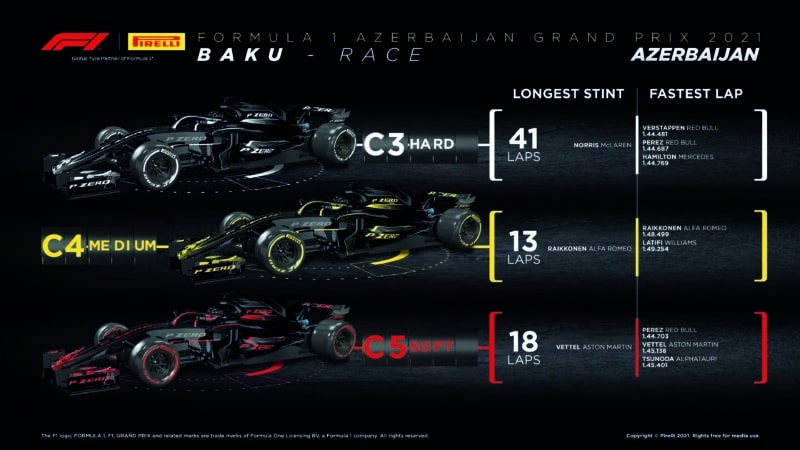

Strategy presented something of a dilemma at Baku, partly because of the complications in choice of wing level (see Tech), partly because of the behaviour of the softest tyres in Pirelli’s range here, the C3, C4 and C5.

Skinny wings were good for qualifying, bad for rear tyre degradation in the race. So wing choice became an intrinsic part of a team’s strategy choice and there was an element of game theory to that. The best trade off between qualifying and race pace could depend on what wing choices your immediate rivals made.

Neither the C4 medium compound nor C5 soft tyre were reliably capable of long stints around Baku and their degradation rate was high enough that the hard would be faster than the medium after around five laps and faster than the soft after around seven.

But the hard was as much as 1.4sec slower than the soft on a single new-tyre lap and 0.6sec off the medium. It could also take a couple of laps to get up to full temperature. The medium did not offer a worthwhile range advantage over the soft – so there was no motivation for the top teams to use it in Q2 and make it their starting tyre. Everyone therefore did Q2 on the softs.

Barring safety car complications, the implication of all this for the top 10 starters was that the opening stint would likely be short and from there you’d get straight onto the hard tyre (which had a Pirelli-estimated range of 40 laps) to get you to the end of the race. That’s where the undercut/ overcut problems arose. At the time of the stops, the car pitting first would be on the slow-to-warm hard tyre on its out-lap. The rival car on its in-lap would be on old, worn softs. Which would be faster between the cold new hard tyre and the warm old soft one? The answer to that would determine if it was better to try to undercut or overcut. But there was a variation in that answer between cars because of the choices of wing level. That variation was purely a function of the highly unusual layout of this particular street circuit making such diverse wing levels feasible.

Leclerc’s rear tyres faded fast enough that he had to pit after just nine laps and such was his pace on the out-lap that Gasly was able to run two laps longer and still overcut him. Similarly, Hamilton’s tyres were fading by the time he pitted on lap 11, allowing both Red Bulls to overcut him (albeit aided by a delay at his stop). Those cars were able to overcut because they’d kept their tyres in shape. The victims were vulnerable because of how quickly their choice of small wings had induced the tyres to fade.

If you could make the soft tyre last more than the 10 or so laps that was expected, it opened up an interesting strategic possibility, particularly for cars outside the top 10 which would be able to start on new rubber rather than the three-lap-old tyres of those who’d got through to Q3. Aston Martin’s Sebastian Vettel was a great example of this. Starting 11th, the German was able to run a first stint between six and 10 laps longer than the frontrunners (which put him into a temporary race lead just before his eventual stop). This offered two bonuses.

If there had been a safety car after the frontrunners had stopped but before Vettel had, he’d have been able to knock around 10sec off the time penalty for pitting, as the field would have been held to safety car vector speeds. This would have brought him onto the tail of Hamilton.

The near-inevitable safety car interlude didn’t happen at that point, but his late stop still meant that his second stint tyres would be much newer than those around him. That grip advantage was what aided him in putting immediate passes on both Leclerc.

Tyre-d out: This graphic shows the superiority of the harder-compound Pirellis in Baku, which could run significantly longer, and were just as fast as the softs

Pirelli