Targets were set to reduce structure weight so that as much ballast as possible could then be added as low as possible within the coming car, and which could then be placed to tune car balance and handling. Degradation rate of the Bridgestone tyres was closely studied to identify optimum wheel camber and toe stiffness. Ferrari’s wind tunnel was working three shifts seeking any and every advantage, since in recent years McLaren aerodynamic performance had been considered superior.

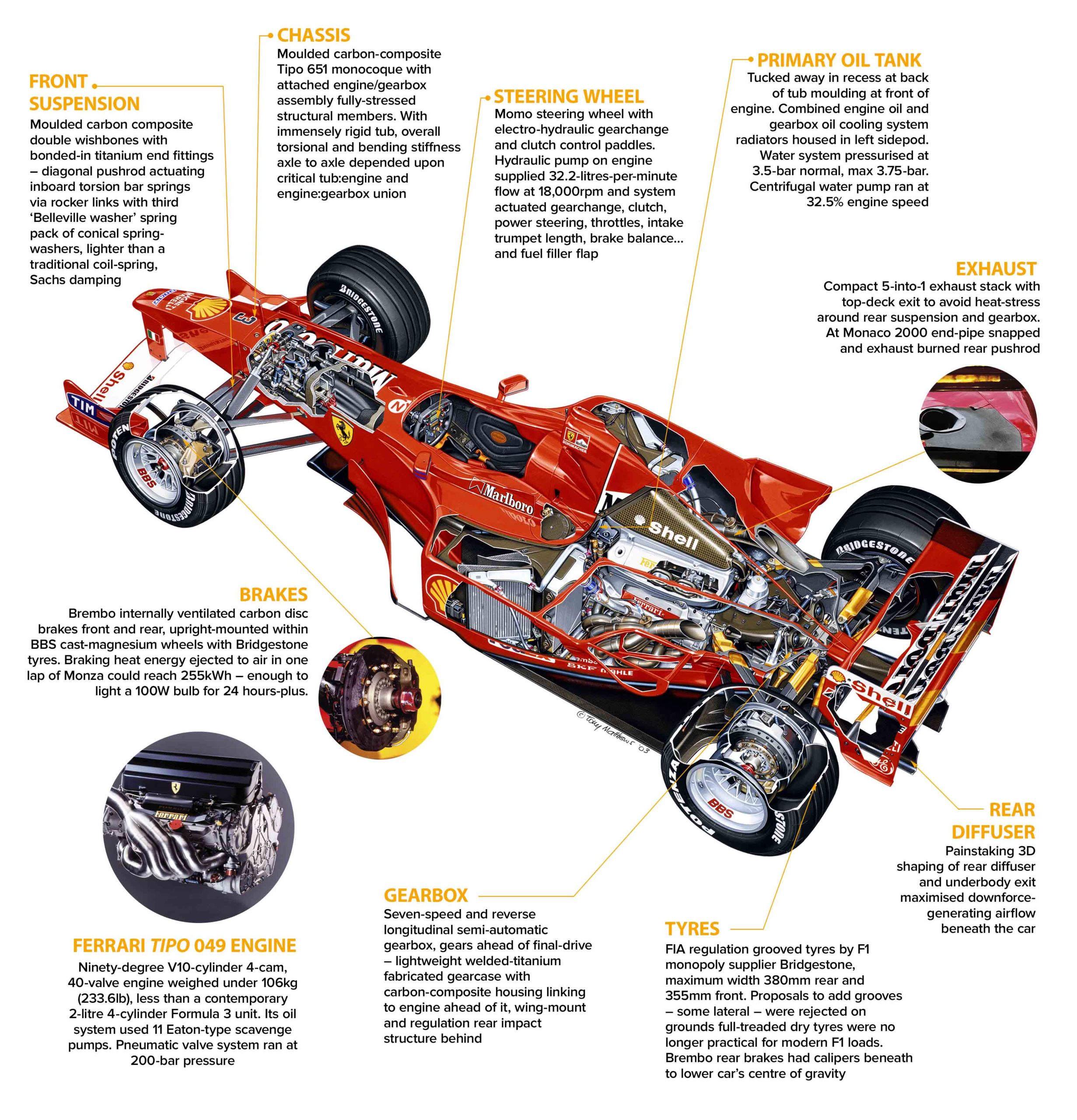

The forthcoming new Ferrari’s carbon-composite monocoque fuselage carried a redesigned V10-cylinder engine, forming the rearward half of the load-bearing structure, accepting all rear suspension, tractive and torsional inputs. When Formula 1 had returned to a 3-litre capacity limit in 1995, the V10-cylinder engine format was adopted as the optimum to combine combustion and thermal efficiency with neat packaging and a good length/cross-section structural compromise. Very short-stroke design enabled the crankshaft to be lowered within the power unit, providing a lower centre of gravity height, pursuit of which also led Martinelli’s design group to consider a wider vee-angle than the V10’s traditionally ideal 72 degrees. Initially Ferrari had gone from that included angle between the engine cylinder banks to 80 degrees in their 047 unit, which had a CoG height of 204.5mm (8.05in). Modification to the still-80-degree 048B V10 spec then cut 7mm off that height, while Martinelli’s new 90-degree 049A V10 design for 2000 – Ferrari’s sixth V10 iteration – slashed it to 187mm (7.3in).

Schumacher’s title came here at the Japanese GP

The engine featured classical twin overhead camshafts per cylinder bank actuating four titanium valves per cylinder with a pneumatic spring system. The underside of each shallow, large-diameter piston was in part cooled from below by carefully directed oil sprays. Obviously by 1999-2000 the era of onboard management unit computer control was well advanced and one F1-2000 system it handled involved variable-length intake trumpets to provide optimum torque delivery, while throttle and gearbox control were both drive-by-wire, freeing the monocoque design from having to accommodate rigid rod or cable linkages.

Ferrari’s 049 V10 would rev to 18,000rpm, and developed some 823bhp at 17,500rpm. Both crankshaft speed and power output were new records for Maranello. This engine drove through a seven-speed semi-automatic sequential-change longitudinal transaxle. Its lightweight carbon-composite structure accepted suspension loads while the titanium gear case beneath and to the rear also supported the rear wing and regulation impact structure.

“Ferrari’s 049 V10 developed some 823bhp at 17,500rpm”

From its winning debut in Schumacher’s hands at Melbourne, with team-mate Rubens Barrichello second, relatively few changes were made to these F1-2000 team cars. Five front wing designs were used, introduced at Melbourne, Imola, Montreal, Hockenheim and Suzuka, three rear wings and three diffuser planes – one virtually standard for most of the year, for the faster circuits and another for Spa. In France, McLaren-like sidepod air-relief chimneys appeared but were not raced until Hungary, then Malaysia, while flip-ups were added ahead of the rear wheels.

Up to 70kg of tungsten (much denser than lead) ballast was carried to ensure the car always hit the 600kg minimum weight limit if checked. Two vee-shaped pieces mounted into each side of the under-nose splitter section, and to reduce rear tyre wear at Silverstone 30kg in a tungsten slab was carried further forward in the leading-edge of the horizontal underfloor.