Max Power: the force of Mosley

He may have been controversial, but Max Mosley’s forthright manner at least got things done. Maurice Hamilton recalls his own run-ins with the FIA president, and why thousands should be thankful for his work in road safety

Authors of many epitaphs on Max Mosley found the need to make heavy use of a thesaurus. One writer, searching for an alternative to ‘calculating’, had liberally sprinkled his piece with ‘unsavoury’, ‘antagonistic’, ‘Machiavellian’, ‘malicious’ and ‘vindictive’; adjectives which, in certain moments of Mosley’s 81 years, played their part. But by no means did they define the whole when it comes to assessing his contribution to motor sport and the wider world.

As motor sport correspondent for The Observer, we had our moments, but never crossed swords. For someone who understood and respected the right to express a point of view, it was not in Mosley’s character to engage in table-thumping argument. We always agreed to disagree over the occasional column that had annoyed him because of its perceived inaccuracy. The worst offender in his eyes was a full-page commentary one week after the debacle at the 2005 United States Grand Prix. Seconds before the start, 14 cars had pulled into the pits, leaving just six to race in front of a disbelieving and outraged crowd. I accused Mosley of ‘mismanaging the crisis’ and claimed he was out of touch with the sport’s fundamental obligation to the paying spectator and global TV audience while he, as president of the FIA, laid down the law by remote control from his apartment in Monaco.

‘Law’, in fact, was the critical word. As a former barrister, the Rule of Law was as essential to his way of life as the right to conduct it as he saw fit (something Rupert Murdoch and the News of the World would later learn to their cost). Mosley argued that Michelin had failed to provide a race-worthy tyre (the left-rear could not cope with the 190mph stress imposed by the Indianapolis banking) and Bridgestone should not be penalised as a result. While some of the solutions proposed by the Michelin runners were marginal, none seemed as daft as Mosley’s suggested compromises (the worst being that Michelin runners should back off on the banking). His refusal to concede, while technically valid, led to a farce that would have a deleterious effect on F1’s reputation in North America. Mosley did agree that some of the alternatives to go racing might have been viable and said he could see my point – but this was irrelevant when it came to his responsibilities as president. Even when we later met on other business following his retirement from the FIA, Mosley would, if the opportunity arose, remind me of the importance of law; an indication the Indianapolis question continued to niggle, even if he did not mention it as such. (‘Max Factor Gives Fans the Finger’ – the headline over the offending feature – probably hadn’t helped.)

The Michelin saga was nothing compared to an infinitely more serious examination of his role as FIA president in the aftermath of Imola 1994. The death of two drivers (Roland Ratzenberger and Ayrton Senna) in a single weekend was exacerbated less than a fortnight later when Karl Wendlinger was knocked unconscious during Monaco practice.

Mosley worked closely with Sid Watkins to improve safety in F1

The hysterical global reaction was summed up by the headline ‘Arrête Ça!’ (Stop This!) splashed across a full-page picture of the crashed Sauber in L’Equipe when the French sports newspaper landed on Mosley’s desk. Avoiding knee-jerk reaction but responding quickly – and being seen to act swiftly – Mosley took steps to reduce F1 performance while initiating long-term research into improving driver safety. At a time when the cry to have motor sport banned globally and instantly was rampant, racing managed to continue thanks largely to Mosley’s calm authority. It was an example of how he was well-versed in both sides of the argument thanks to being a former driver and director of the March F1 team.

Mosley was less familiar with the road car industry, as he later discovered when searching for information on F1 crash tests. Having formed a working committee with Professor Sid Watkins (the respected neurologist and FIA safety delegate) and others, Mosley was certain the automobile industry would have useful research. He was appalled to discover there was virtually none. Worse than that, the manufacturers were calling the shots and avoiding the implementation of road car safety features on the grounds of cost.

When Mosley was effectively told not to meddle in something he did not understand, the industry was unwittingly guaranteeing the opposite reaction. By structuring car safety performance and conceiving first Euro NCAP (New Car Assessment Programme), then Global NCAP Mosley and his team undoubtedly saved many thousands of lives.

Euro NCAP was a huge achievement.

His contribution to road safety will be celebrated in new film, Mosley: It’s Complicated, to be released this month (July). It is produced by Michael Shevloff, and I acted as a consultant, specifically on the motor sport content. It is an unflinching look at his remarkable career and he speaks with disarming clarity on matters such as the newspaper sting on his sadomasochistic pastime in a Chelsea basement. But neither did he shy away from what had clearly been the truly agonising loss of his son, Alexander, due to a drugs overdose.

Mosley made no apology for his role in motor sport-related controversies such as the ‘Spygate’ affair in 2007 when McLaren was found guilty of being in possession of technical information belonging to Ferrari. When a US$100m fine was handed down, Mosley denied this had anything to do with his earlier view that Ron Dennis was ‘not the sharpest tool in the box’. That publicly expressed summary of the McLaren boss did, however, highlight Mosley’s sometimes juvenile mindset and barely concealed disdain for any self-important adversary lacking his razor-sharp intellect.

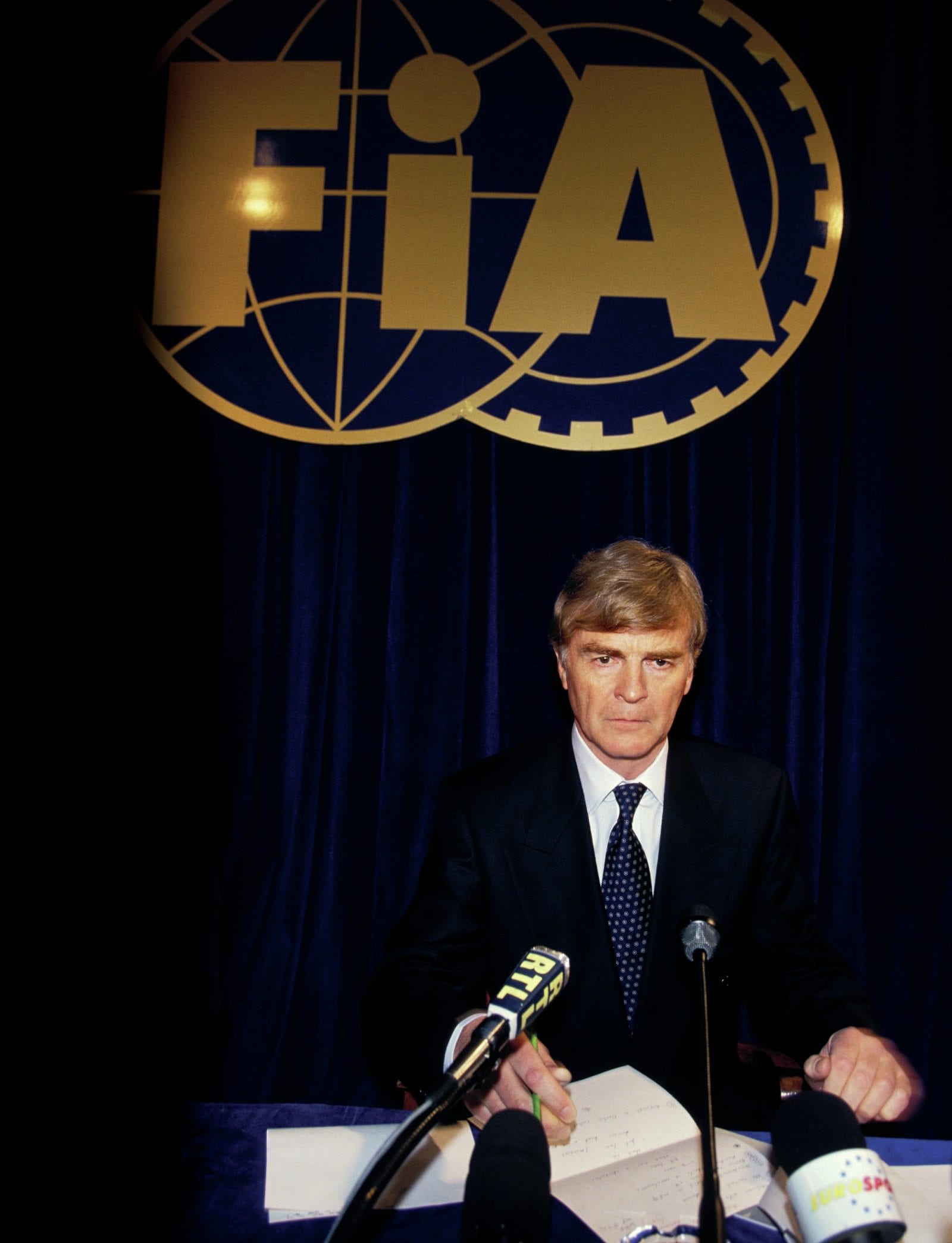

Announcing the World Federation of Motorsport in 1980, a key moment in the FISA-FOCA war.

The thought of conducting an interview with Max felt like preparing to go down an interrogatory path riddled with verbal trip wires of your own making. A lunch in 2011 was one such occasion. I wanted to hear his explanation for apparently selling F1’s commercial rights for a song to his old mate Bernie Ecclestone. There could be no argument about how these two –a mutually respectful combination of streetwise former car salesman and a patrician legal brain, erudite in several languages – had worked hand-in-glove to lift F1 from a shambling collection of racers to a slick, well-funded operation. But to let the accumulated goodwill go for US$360m seemed, if not careless, then culpable of cronyism.

Having given this much thought, lined up my arguments and carefully worded the question, the result was a familiar one, not just to me but to many of my colleagues. ‘Yes,’ he would gently reply, ’that’s a very good point. But, you see, there’s a problem with what you say. Point 1, let’s look at…’ By the time he had reached points 4 or 5, your mind would either be spinning, or you would be agreeing and giving thought to apologising for a silly question.

I continue to struggle with his justification for the Ecclestone deal – even if some of that $360m did help pay for the NCAP project.

New film

Max had been coping with cancer for longer than we knew. He never spoke about it, but it was raised during a telephone call 10 days before his death. His view was typically logical: “I suppose if you’re going to die, then it’s either cardiovascular or cancer,” he said, matter-of-factly. “And probably this is better in the sense that you’ve time to get your affairs in order – in contrast with somebody like poor Charlie [Whiting, the FIA race director who died suddenly of a pulmonary embolism, aged 66].”

Getting his affairs in order included finding time to reflect on the multifaceted life portrayed in the film. “It felt very strange looking at the film. To me, it’s like watching somebody else. The references to NCAP are important because I think NCAP really matters. I was the catalyst, I guess. At one stage in the film, I make the point that if somebody puts you in a position like the president of the FIA, you are uniquely placed to make a difference. And it’s noticeable how many people occupy such a position, but do bugger all. The fact that you have been able to do something – even if it were saving the lives of just a few people – is really significant. And when it gets to be thousands, it’s extremely significant. You sort of feel; well, if I never do anything else, at least that was worthwhile.”

Mosley particularly enjoyed a tongue-in-cheek quote in the film from Marco Piccinini, former Ferrari race director: “Max? An excellent engine, powerful acceleration – some problem with the brakes.”

“I wouldn’t disagree!” said Max. “It’s not for me to say about the good engine and such, but I would certainly confess to being a bit slow in applying the brakes on occasions.”