Donington Park Grand Prix, 1938: Frozen in time

A newly discovered cache of photographs paint a vivid picture of Donington Park on the eve of war and offer a glimpse of a world that would soon disappear forever. John Bailie tells their story

The late October sun casts its shadows across the pitlane as the Auto Union and Mercedes teams assemble for practice before the 1938 Donington Grand Prix, one of an amazing gallery of recently discovered images.

From the first loose-surfaced tracks of 1931 to staging four grands prix, Donington Park’s expansion in just a few years was astonishing.

The unlikely but formidable partnership of John Gillies Shields, 74-years old when the circuit opened, by now an alderman and the owner of the entire Donington Park estate, and Fred Craner, half his age, garage owner and energetic secretary of the Derby and District Motor Club, had taken the circuit to world-class standards, although some of its rudimentary facilities remained out of step with the development of the track itself.

That’s what makes this collection of images extra special. Shot on 35mm Agfa colour film, they were recently discovered by Edinburgh-based Donington devotee Philip Hall. Never published before, and taken by an unknown photographer, they vividly capture, despite their much-faded hues, the relaxed ambience of a virtually deserted circuit on a practice day before the 1938 Donington Grand Prix.

Along with several wonderfully atmospheric shots showing the German team cars in the pitlane and images of Mercedes, Auto Union, ERA and Delahaye making practice runs on a track devoid of spectators, they show, for the first time and in incredible detail, the environment around the farm buildings that formed the base for the crack Mercedes and Auto Union squads.

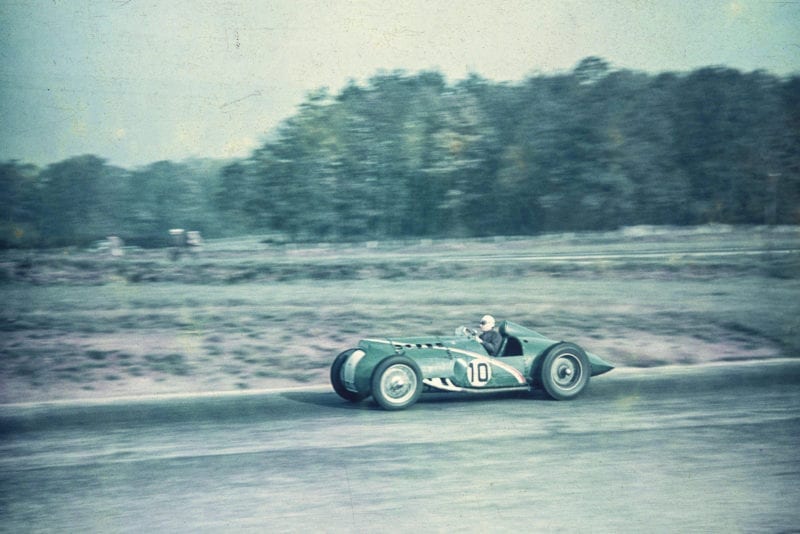

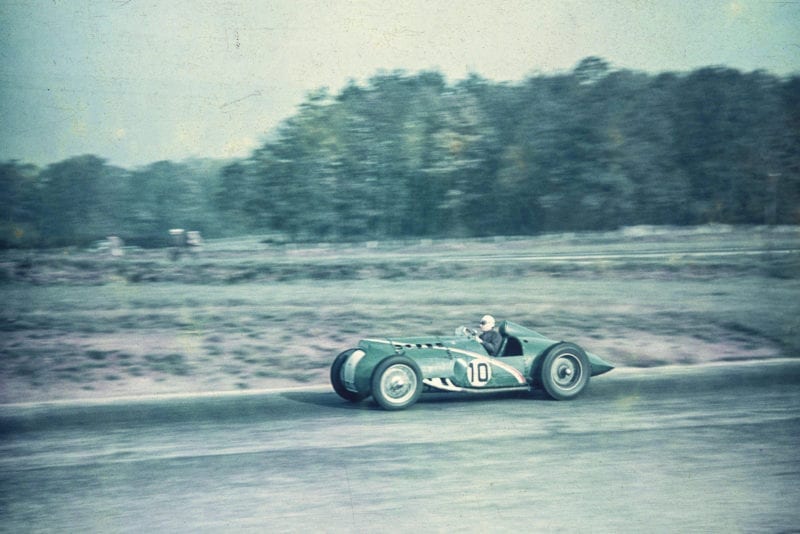

This is the V12 4.5-litre Delahaye that was driven to victory by Rene Dreyfus in the Pau Grand Prix in April 1938, defeating the Mercedes W154 shared by Rudi Caracciola and Hermann Lang in the process. It is pictured on the downhill dash to the Melbourne Hairpin, part of the pre-war circuit that survives to this day. At this time the Ecurie Bleue team were riding on notable Delahaye successes having won the Prix du Million Franc prize at Montlhéry the previous year, and two weeks after Pau the Cork Grand Prix also fell to Dreyfus, all in this car. Expectations were high at Donington but this optimism gave way to disappointment, the car retiring early in the grand prix with oil pressure problems.

Since 1937, the track had been improved. The gradients of the Melbourne Rise that enabled the Silver Arrows to become airborne had been eased slightly and the McLeans – Coppice stretch widened, but the squeeze through the farmyard remained.

It was a major achievement that the German teams were even present at Donington in 1938. Due to the Munich Crisis, and the gathering war clouds, they had arrived at Donington only to be instructed to return. Twice this had happened, their return journeys via Harwich docks curtailed by last-minute instructions from the German authorities, messages relayed to the teams at roadside AA boxes and, of course, the persistent persuasion of the indefatigable Craner. The teams were to arrive back at Donington for a third and final time, the race taking place on Saturday, October 22; it was certainly worth waiting for! Those days are long gone, but images such as these preserve the memory forever.

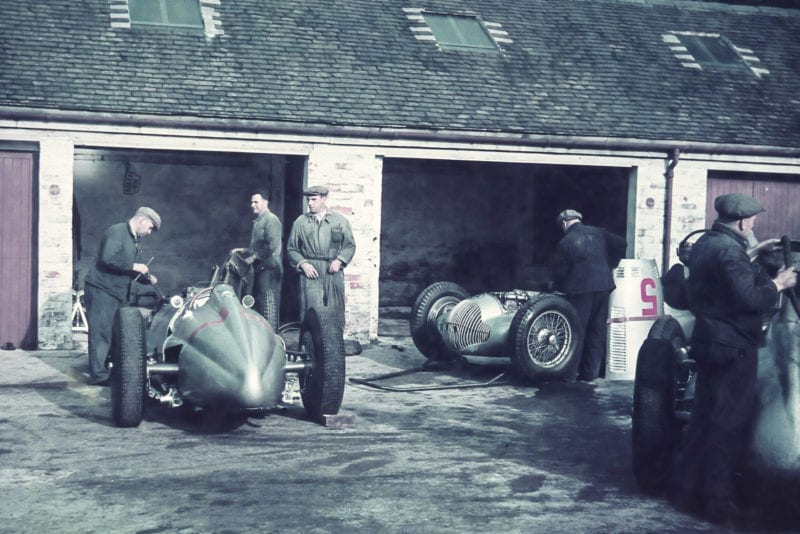

Auto Union mechanics hard at work on the supercharged V12 engine of Christian Kautz’s Type D. Rudolf Hasse’s car sits alongside. Both drivers would crash and retire from the race. Beyond them is the Melbourne Brow, site of so many 1937 images of airborne Silver Arrows, leading on to the start/finish straight and then the sharp left turn of the old Redgate corner and through today’s race paddock.

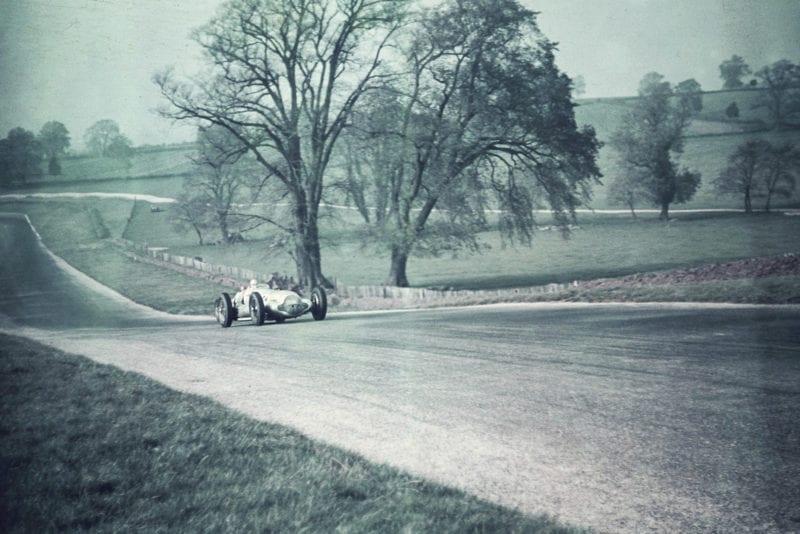

Donington’s still wooded parkland provides the backdrop for this shot of one of the Mercedes W154s on the approach to the Melbourne Brow. It shows just how steep the rise was, although the crest itself had been eased for 1938. This is presumably the team’s spare or practice car, hence the ‘P’ it carries. Or possibly it stands for Prova, left over from the team’s previous race, at Monza. Each team driver could try it to learn the circuit or bed in tyres.

Band leader Billy Cotton in the ERA he shared with ‘Wilkie’ Wilkinson in a shot that emphasises the width of the start/finish straight and the nature of the heavily wooded Donington Park estate. Only a raised kerb separates the pitlane from the track. Cotton/Wilkinson would finish in seventh place in the grand prix, with the similar cars of Dobson and Ian Connell/Peter Monkhouse finishing sixth and eighth (last). They were the only three non-German cars to finish, a minimal satisfaction for the outclassed ERA team.

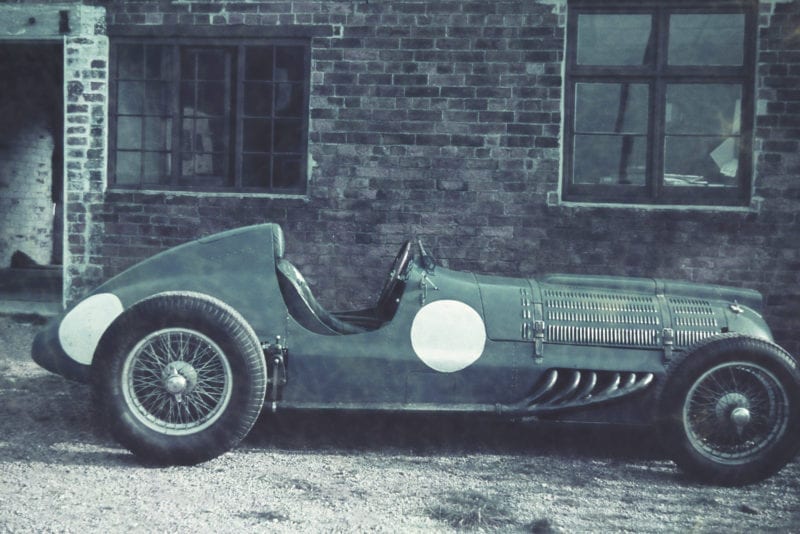

The troublesome Delahaye 155 sits alongside the outer wall of the quadrangle of barns that formed the Mercedes base. Entered for Dreyfus to drive but raced in the event by ‘Raph’, it retired after 10 laps. Only one example of this car was made, and while it shared the same engine as the successful 145, it would achieve notoriety as the “worst car that Delahaye made”. Dreyfus stated: “The monoposto Delahaye was all wrong at Donington. The engine was good, but the car just wouldn’t stay on the road. So I drove my Pau car in the race.”

The Pau GP-winning Delahaye 145 sets off down the 11⁄4-mile downhill straight to the Melbourne Hairpin. This section of the circuit was little more than a farm track through open countryside when Fred Craner first hatched his plans to turn Donington into a race track back in 1931. The inner leg of the little-known Manufacturers’ Circuit, now the part of the modern day circuit between Coppice Corner and the Esses, can be seen in the distance to the right. The former Donington Collection museum buildings would be just to the left of the picture.

Auto Union cars lined up in the pitlane, in preparation for practice runs. Note the quick-lift jack supporting the wheel-less D-type, and the gravelly road surface.

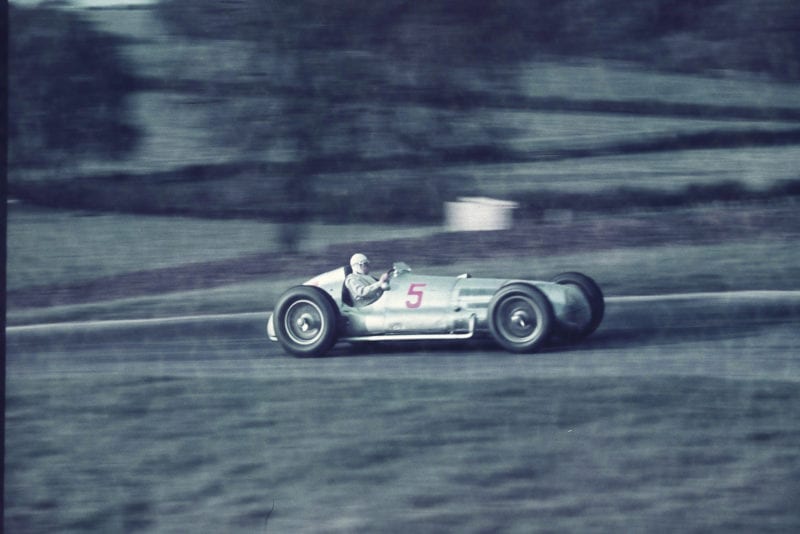

With Caracciola sidelined through injury, recently recruited reserve driver Walter Bäumer took over his W154. He’s shown here driving on the uphill approach to the Melbourne Brow. He was to retire in the grand prix on lap 43.

Accustomed to the more refined facilities of continental circuits, Mercedes team chief Neubauer must have been taken aback when told his team’s base would be in a cobbled farmyard when they first arrived at Donington for the 1937 race. However, Mercedes returned to the same environment in 1938, hoping to better its previous result when Rosemeyer’s Auto Union beat the Mercedes of von Brauchitsch and Caracciola into second and third places. Here, mechanics work on Lang’s (no7) and Bäumer’s (no5) cars within the quadrangle of barns opposite Craner’s farmhouse home.

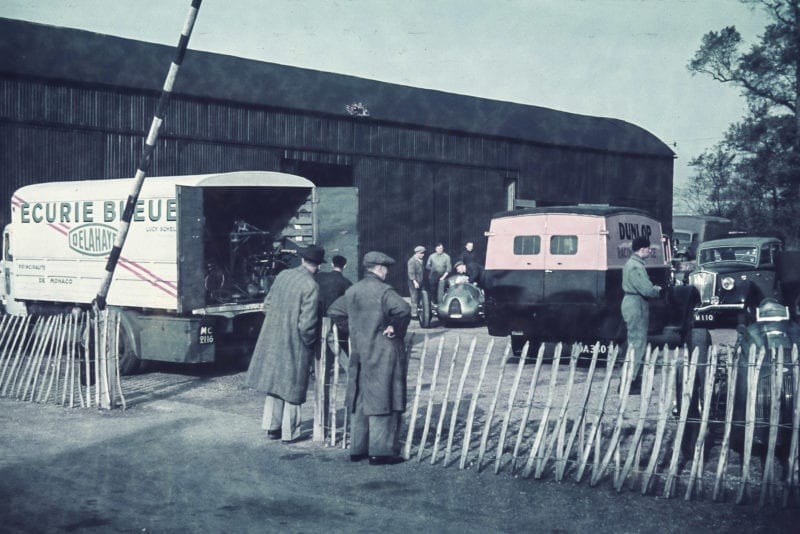

In a view looking back towards Coppice Corner, the Ecurie Bleue Delahaye 145 is taken out for a shakedown by a mechanic. The team’s liveried Delahaye truck is parked in the compound, the wicker fence all that separated the area from the track. Coppice Farmhouse would be just outside this image, to the right, the gap between it and the barns forming the narrowest part of the circuit. The corrugated iron-clad Dutch barn on the left was the base for Auto Union.

Another image from Philip Hall’s collection showing a Mercedes about to crest the Melbourne Rise. Hardly a blade of grass would be visible on race day, when a record-breaking crowd of over 60,000 descended on Donington Park to witness Nuvolari’s victory.

This atmospheric image from Philip Hall’s collection shows Nuvolari’s Auto Union being wheeled out of its Dutch barn base between the Ecurie Bleue service lorry and the Dunlop Racing Services support van, while two spectators look on from the edge of the race track. The monoposto Delahaye 155 is visible behind the rustic fence; the Wolseley saloon was used to transport Nuvolari from hotel to track.

The late October sun casts its shadows across the pitlane as the Auto Union and Mercedes teams assemble for practice before the 1938 Donington Grand Prix, one of an amazing gallery of recently discovered images.

This is the V12 4.5-litre Delahaye that was driven to victory by Rene Dreyfus in the Pau Grand Prix in April 1938, defeating the Mercedes W154 shared by Rudi Caracciola and Hermann Lang in the process. It is pictured on the downhill dash to the Melbourne Hairpin, part of the pre-war circuit that survives to this day. At this time the Ecurie Bleue team were riding on notable Delahaye successes having won the Prix du Million Franc prize at Montlhéry the previous year, and two weeks after Pau the Cork Grand Prix also fell to Dreyfus, all in this car. Expectations were high at Donington but this optimism gave way to disappointment, the car retiring early in the grand prix with oil pressure problems.

The 1938 Donington Park practice session

From Motor Sport Magazine, November 1938

Though the Auto-Unions no longer flex and dither as they did last year, and though the German cars no longer leap from the rise after Melbourne Corner, where the bump has been eased off, nevertheless, in speed, sound and acceleration the 3-litre Formula cars make other racing look just stupid. As I write, some of the drivers play impromptu football, others clock-golf, on the sun-lit lawn outside Donington Hall, where, as last year, they have all lunched together — all, that is, save Seaman. Seaman appeared to arrive late and to exchange a few words with Neubauer.

Early this Thursday morning Uhlenhaut took out the Mercedes training car, labelled with a big “P” and committed much lappery. This car had an extra air-temperature thermometer clamped to the scuttle side. Uhlenhaut wears full kit and will apparently be the team’s spare driver. Soon the other drivers get down to it, including Nuvolari, who sets up the fastest lap. After lunch there is less activity, Seaman doing very little and Nuvolari nothing at all. But Lang does one immense lap. Hasse, in black overalls, is very cheery, but Kautz suffers from a cold.

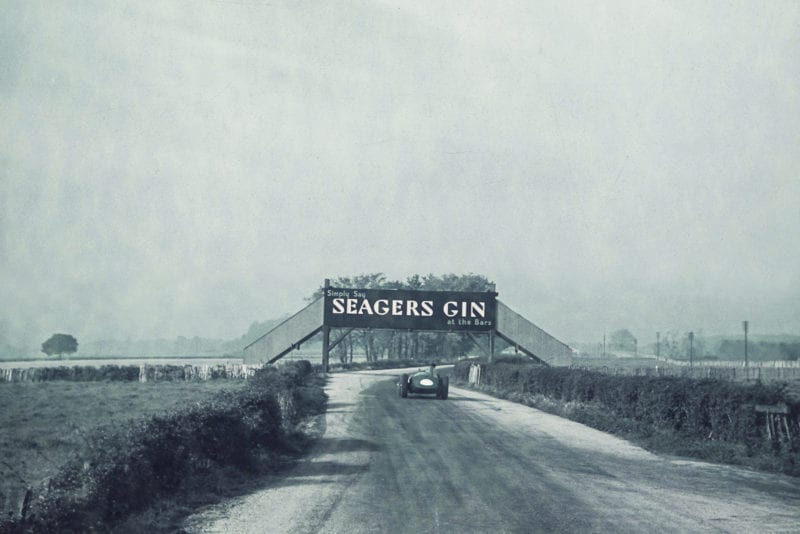

Another 1938 Donington Grand Prix practice day scene…A car departs on a shake down run along the 1 1/4 mile downhill stretch to the Melbourne Hairpin; it could be an ERA but is it the Alta of Robin Hanson that caused the drama during the race at the Old Hairpin when it liberally distributed its oil all over the track.

Another pointer to this viewpoint is that, 35 years later, Donington saviour Tom Wheatcroft would open his Grand Prix Collection museum in newly erected buildings in the area to the left of the picture. The black corrugated iron-clad Dutch barn, used by the Auto Union team as its Grand Prix base, is the dominant feature to the right. It would become the ERA company’s base for a brief period from mid 1939. It’s now on a Leicestershire farm!

To walk all round the circuit is a truly wonderful experience. Through the wood beyond Red Gate the cars sound terrific, and their speed down to the hairpin is prodigious, but perhaps the most spectacular point is from Maclean’s Corner, along the straight bit to Coppice Corner. Here one is able to appreciate very thoroughly the work done by the drivers, all of whom perspire freely after only a short spell in the ” seat of government” Hasse keeps his hands comparatively steady on the wheel on the straights and Seaman slides beautifully into Red Gate. Frequently the cars visit the grass verge at Melbourne and they come out of the woods like bombs, sliding sideways through the gate.

At the pits we see again the amazingly thorough organisation ; every lap timed, copious notes made of every piece of work undertaken, and cars continually given flag signals by their respective chiefs. At the depots one’s breath is again taken away by the astoundingly complete equipment. The tyre-store, in charge of Continentals’ imposing representative, is a wonderful sight, and Mercedes alone brought more than eleven hundred gallons of special fuel.

They shall not pass

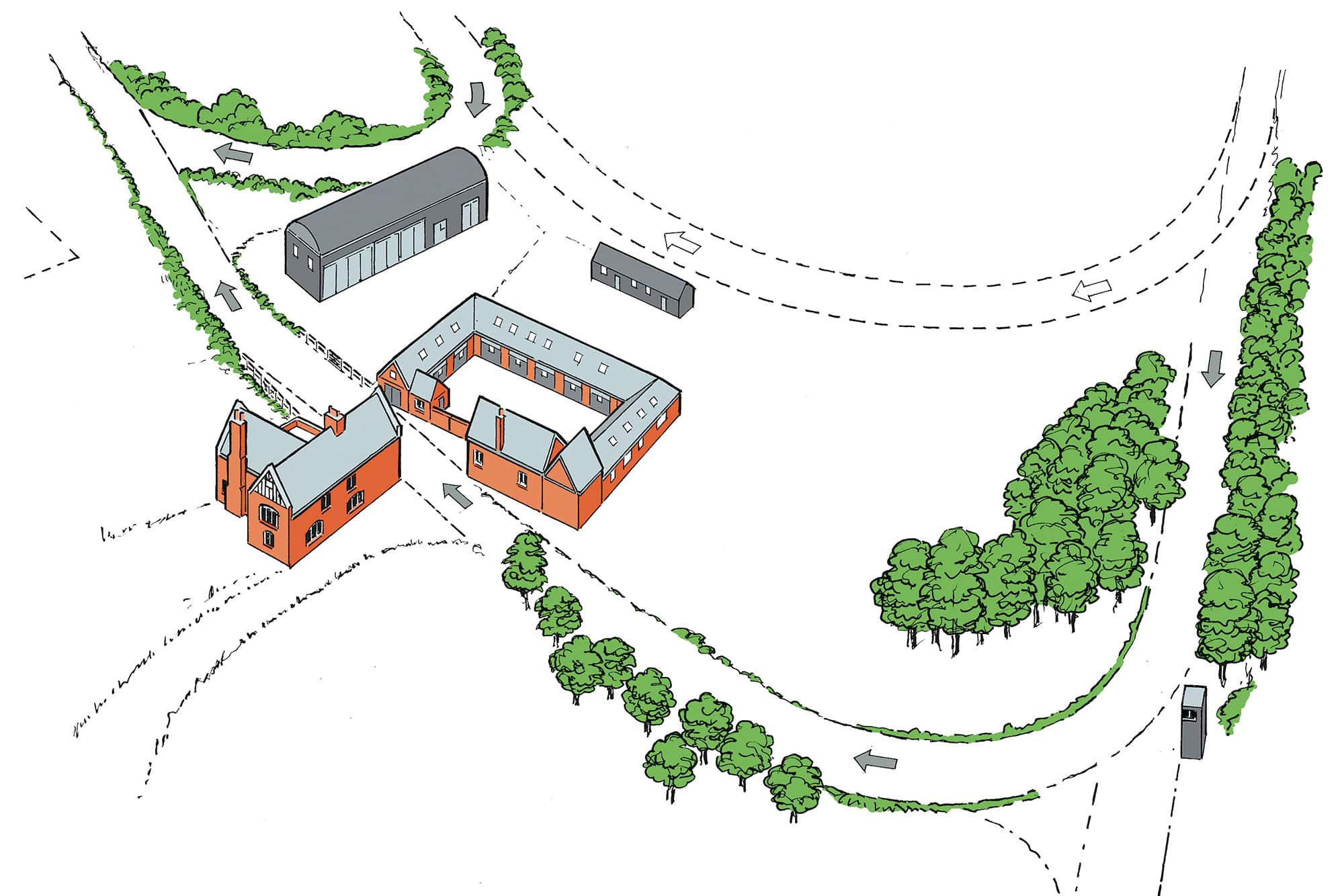

This shows how the track squeezed through the former farmyard, between the barns and the gable end of circuit creator Fred Craner’s home, Coppice Farmhouse, a ‘no passing’ zone. The barns are long since demolished but the farmhouse – until recently the circuit’s administration offices – stands deserted, the sole remaining physical monument to that epic period. The main paddock, comprising 30 covered bays each holding two cars, together with offices and parking space for transporters, was located further on, nearer to the current paddock entrance. Competing cars would travel around the Melbourne Hairpin to reach the start/finish straight on the return leg of the loop, where the current circuit offices and other businesses are now located at the west end of the current race paddock.