Niki Lauda's second comeback

Maurice Hamilton, the author of a brilliant new biography of the triple world champion, explains that while Lauda’s first Formula 1 comeback was heroic, his second was just as remarkable...

Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images

If anyone had been unaware of Niki Lauda’s return to the cockpit in January 1982, they knew all about it on the morning he was supposed to make his official comeback. The then two-time World Champion turned up at Kyalami and urged his fellow drivers to go on strike.

Lauda may not have been militant, but he had a keen awareness of what was right and wrong. In his mind, the recently introduced superlicence – specifically a clause tying a driver to his team in the fashion of football contracts – set a dangerous precedent that would cut the legs from beneath a driver’s independence. That may sound obvious but, of the 31 drivers preparing for the 1982 season, Lauda had been the only one to spot it. Or, more likely, the only one to bother examining each clause in detail.

Lauda’s previous F1 experience, extending across more than 100 grands prix, was also enough to tell him that one move would be crucial if he was to make a walkout effective. He would need to act before the drivers reached their teams and the influence of managers that would range between powerfully coercive and potentially threatening. The element of surprise would be made possible by positioning a bus at the circuit gate, ready to whisk the drivers out of reach shortly after their arrival.

Lauda also knew that a silent race track would be a powerful tool, one that would subsequently help win the day. Following an overnight stay in a temporary dormitory in a hotel function room, the drivers returned to begin practice. Despite much blustering by Jean-Marie Balestre, the president of the governing body, the offending clause was removed. Lauda’s presence could not be denied. But the real reason for it remained unclear, for the time being.

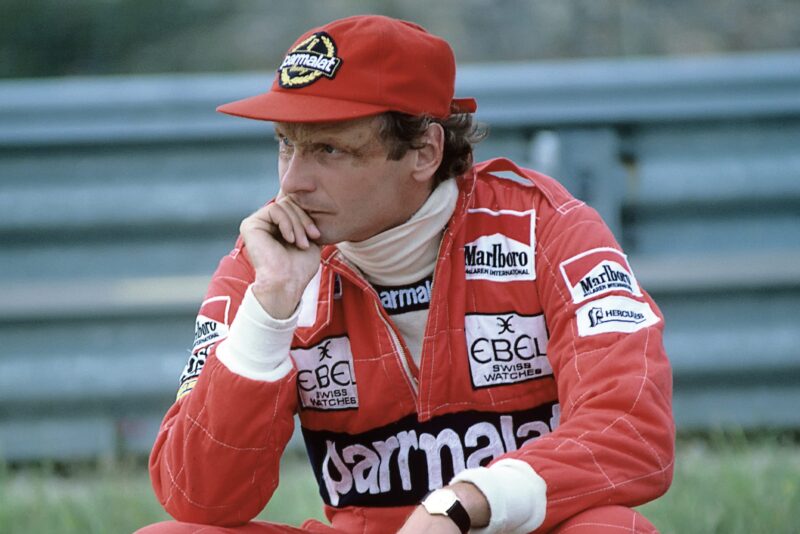

Lauda walked away from F1 in 1979 and showed little interest in a comeback. Three years later here he is at the Monaco GP, like he’d never been away

STF/AFP via Getty Images

Comebacks, particularly at the top level of any competitive sport, were treated with a mix of interest and suspicion. None more so than that of Lauda. He had climbed from his brand-new Brabham halfway through the first day’s practice for the 1979 Canadian Grand Prix and simply walked away. Just 24 hours later, he was at the McDonnell Douglas factory in California, ordering his first DC10 for Lauda Air, the company he had founded in that same year.

Lauda had shown no further interest in F1 until August 1981, when ORF, the Austrian TV network, asked if he would be interested in being a pundit at his home grand prix. Driven by curiosity more than anything else, Lauda accepted.

“There was a big startline crash, and I didn’t feel awful,” said Lauda. “I felt normal; didn’t feel good; didn’t feel bad. This was different for me because, for a year and a half, I had no feeling for motor racing. Whenever I heard something or saw something on television about Formula 1, I thought: ‘don’t mention all that crap’, but this was interesting. The cars are different, and things change.”

“Lauda feigned interest in set-up so he could catch his breath”

Intrigued by the advance in F1 performance, Lauda idly wondered if he could not only drive the latest cars but also enjoy the sensation and, leading on from that, be competitive. His appearance at the Österreichring may have done little to ignite speculation about a comeback but, when he turned up at Monza a month later, the rumour mill went into immediate overdrive.

“I went to Monza on my own because I wanted to check my feelings,” said Lauda. “I saw [ John] Watson’s crash where the engine came off the car [McLaren-Ford MP4/1] because he hit the wall so hard – and even with an accident as severe as that, I thought: ‘Pah! No problem! The risk element is reduced. I don’t care any more; there’s no more fear.’ So the feelings I had before for racing just came back.”

If astute timing plays an important part in the decision-making process of any driver or team, then Ron Dennis had an abundance of it during the first week of September 1981. Sensing Lauda’s curiosity, Dennis asked if Niki would be interested in driving a McLaren at Donington Park, a track removed from the usual run of testing venues and reasonably hidden from prying eyes. Lauda accepted. Ron’s judgement had been pin-sharp.

The same could not be said for Lauda’s fitness. After just a few laps, he feigned interest in a discussion about set-up on the MP4/1, the period in the pits giving him the chance to literally catch his breath. Lauda may have been surprised, but he was not concerned. Applying his usual pragmatism, Niki reckoned he could, with the help of his fitness guru, Willi Dungl, soon reach the required standard.

When you’ve come back from death’s door after a fiery crash five years before, this would be a matter of routine. As would be answering the same two questions that had dominated his thinking at Monza in September 1976: would he be quick enough and would the desire to compete be as strong as before? The 50 or so laps of Donington told him the answer was yes.

The return to racing with McLaren was announced in December. Lauda’s reasoning, although clear in his mind, was not shared by cynics searching for the motivation driving a scarred warhorse who ought to know better.

It was noted that Lauda had cancelled his order for the DC10 wide-bodied jet (due largely to a change of strategy within Lauda Air to match a shifting airline market). The suggestion that he was short of money was advanced by claims that he had been ordered to pay £130,000 in back taxes. Then word came out that he had been called up by the Austrian army and rejected as medically unfit, which, apparently, begged the question of his fitness to fly. When questioned by Britain’s Sunday Telegraph, Lauda nailed each claim in turn.

“First, the tax,” he said. “In 1974, my lawyers went to the authorities who agreed that my income should be paid into a trust fund in Hong Kong, from which I would draw a monthly allowance. I pay tax on that, and there was absolutely no problem until 1978 when they suddenly decided to recheck everything. They went through all my expenses and said I should travel by boat rather than aeroplane. ‘Listen,’ I said, ‘If I ever go back to racing and I go by boat, the race will be over before I get there.’ Then they asked things like ‘Where were you on August 17, 1975?’ They fought me like hell, and, in the end, I had to pay. I checked it out properly, and they now agree that I can fly wherever I want. The tax people also checked with the army. Although there is national service for people under 35, I think they had forgotten me. Then I had a letter to go for a medical. It took just two minutes. They said I was not fit enough to join because of my burns. I said: ‘Thank God” and left. Next day it was in all the papers, and the civil aviation authority made me have three separate medicals before I could continue with my flying license. I am Austrian, and I like living here, but I don’t see why the government make it so difficult for me. I don’t care how people interpret it [his comeback]. The only motivation is enjoyment.”

Back on the scene: Lauda returns to F1 at Kyalami in 1982, three years after he exited

Gilles Levent/DPPI

But what about his speed? Given his poor level of fitness during the Donington test, Lauda had been reasonably satisfied when comparing lap times with the benchmark set by John Watson in the same car. The real test would start in South Africa – once he had taken care of the contractual and political wrangling. Never one for the loud statement, Lauda played himself in gently and finished a respectable fourth at Kyalami. He might have gone one better at the next race in Brazil had he not been nerfed by the Williams of Carlos Reutemann. By round three in California, he was back on song – in and out of the car.

Setting the fastest time at the end of the first day’s practice meant he was duty-bound to face the media, which was not a matter of routine at races outside North America.

With much to discuss with his engineer about the McLaren MP4/1B, Niki was not best pleased to discover that the press room at Long Beach was in a convention centre, some distance from the pits. Surprise, followed swiftly by bemusement and annoyance among the local correspondents, can be imagined as Lauda marched in, stepped up to the microphone and said: “Tyres good. Engine good. Car good. Goodbye.” Then he nodded and walked off. Amid anguish among American writers with little knowledge of F1 and large notebooks to fill, their European counterparts could only smile and quietly shake their heads. Welcome back Niki Lauda.

Niki eased back into F1, impressing with fourth in ’82 Dutch GP, holding off turbo power rivals

Paul-Henri Cahier/Getty Images

His familiar ways would continue on the track. Applying a combination of speed and experience, Lauda ran third in the opening stages of the grand prix, keeping a watching brief behind the leading Alfa Romeo of Andrea de Cesaris and René Arnoux’s Renault. Just as he was thinking about trying to unsettle the Frenchman, Lauda noticed Bruno Giacomelli dodging around in his mirrors as they charged down the back straight. When Lauda craftily left the door open on the approach to the hairpin, the over-excited Giacomelli accepted the invitation – and tanked his Alfa into Arnoux as they reached the braking area. Lauda’s thoughts were never recorded, but they can be easily imagined as he gratefully accepted second place.

Over the space of the next nine laps, Lauda whittled down de Cesaris’s five-second lead and seized his moment when the Alfa got caught behind a backmarker.

Niki Lauda was leading a grand prix for the first time since the British Grand Prix at Brands Hatch four years before, and he would remain unchallenged for the remaining 60 laps.

The media could easily understand the significance of a remarkable achievement in only the third race of a comeback, Lauda receiving a standing ovation as he returned to the convention centre two days after his first visit. He stayed longer this time. Without waiting to be introduced by the loquacious host commentator, Lauda ambled up to the bank of microphones, and in between gnawing at an apple, barked: “Any questions?” He fielded a number with his familiar, precise answers. When asked which of his 18 grand prix wins he savoured the most, he replied that the last one is always the best. At which point, he nodded crisply once more, called a halt and sauntered off.

Lauda of old: Niki rolled back the years by dominating the ’82 British GP by over 25sec

Adrian Murrell/Getty Images

If he had just savoured a high point of his profession, Lauda was about to be reminded of its terrible flip side at the very next race. During the final moments of qualifying for the Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder, a misunderstanding with Jochen Mass meant Gilles Villeneuve clipped the slow-moving March and somersaulted off the road. The Ferrari driver died in hospital that night.

In common with many inside and outside F1, Lauda had grown to like and admire Villeneuve. Upset by the loss of the French- Canadian, Lauda laid the blame at Mass’s door in such a direct manner that there was talk of Niki being disciplined by FISA, the governing body uncomfortable with Lauda’s direct words. An official enquiry would later attribute the cause solely to Villeneuve’s error and state: “no blame is attached to Jochen Mass”. Such an unequivocal statement angered Lauda even more, and that sense of outrage continued a month later when Alan Henry, F1 editor at Motoring News, introduced me to Lauda in-between practice sessions for the Detroit Grand Prix.

“I was touched by Villeneuve’s accident like never before; that’s a fact,” said Lauda. “I think he was the best driver of his day, taking every factor into account. I don’t want to go into any more details [of the accident] because I’ve done that once. No, it’s not a question of reminding me how dangerous this business can be; not at all. It’s just a question of how the best guy in the business comes to get killed in a stupid accident. These are the facts that worry me and get me very upset.

“I never thought that coming back might be the worst thing I could do,” said Lauda. “You can sit at home and say you want to come back, but then you have to make a major decision about whether you are able to do this mentally. Physically, it’s no problem because you just run and train; that’s the easiest thing you can do. You look at the watch and run for 10 minutes, then 20 minutes or two hours, or whatever, and then you’re fit. But mentally, you can’t train yourself because this is something that changes every day. The rain comes down, you feel miserable. The sun shines, you feel happy. Mentally, it’s been a much bigger fight for me than physically. Things change every day, and you have to adapt yourself differently to the job.”

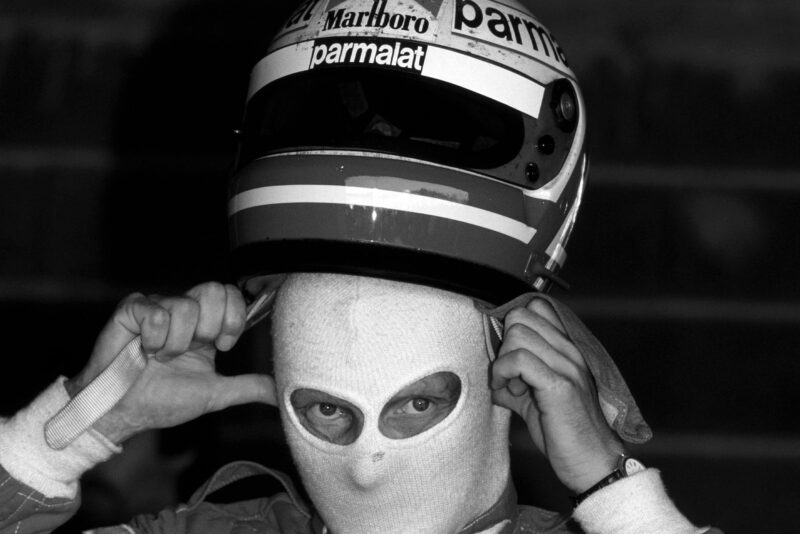

Lauda prepares for the 1982 Swiss Grand Prix

Jean-Yves Ruszniewski/TempSport/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Lauda had turned 33 the previous February, putting him among the oldest drivers on the grid.

“It’s been much more difficult for me than some of these younger guys,” said Lauda. “When you’re 18 and you race for 10 years, you are single-minded, and your brain only works for motor racing because you haven’t done anything differently. Being away from motor racing, spending two years flying aeroplanes or doing other things, you suddenly get a completely different view about everything; you get a wider view.

“So, you come back into motor racing, and you’re up against the other f***ers who are single-minded. They don’t know anything else, and it’s easier for them in a way. On the other hand, I think it’s a big advantage not to be so single-minded because you get a bigger view. I think if you can get your aggression back – the killer instinct, if you like – then this, with a wider view, I think makes you a better driver. I don’t know what the others think: I can only judge myself on my own capabilities.”

Those capabilities were more than enough to put Lauda in the running for the title at the end of 1982 and then securing it by half a point two years later.

As sporting comebacks go, it remains one of the most outstanding, arguably beaten only by his extraordinary display of courage and determination six weeks after the Nürburgring incineration (or ‘The Grill Room’ as he referred to it with typical insouciance).

The underlying tenet throughout is that this extraordinary man genuinely did not see any of it as being out of the ordinary.