Norton: Riding back from the brink

Not for the first time Norton faces an uncertain future after a recent financial scandal. But as a history littered with racing triumphs and comebacks proves, motorcycling’s coolest brand has a habit of surviving. Mat Oxley reports

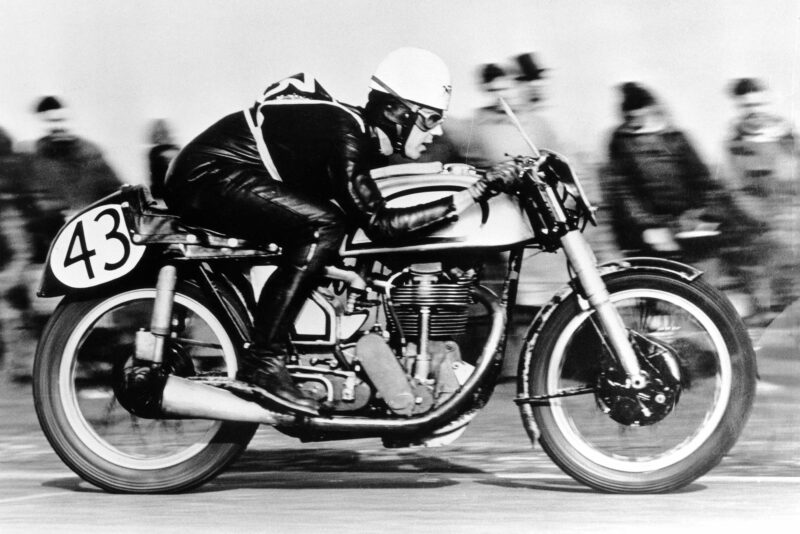

Freddie Frith sets off in the 1937 Senior TT, which he won with the first recorded 90mph lap

Britain ruled the world of motorcycling for much of the 20th century. AJS, BSA, Matchless, New Imperial, Panther, Royal Enfield, Sunbeam, Triumph, Velocette, Vincent-HRD and many other British marques were the envy of the world. But one name always stood out: Norton.

There was a simple reason for Norton’s prominence: the Birmingham brand went racing from the very beginning and never really stopped. As one rival manufacturer said, “the market always follows the chequered flag”.

James Lansdowne Norton’s embryonic enterprise won the twin-cylinder class at the inaugural 1907 Isle of Man TT, dominated grand prix and TT racing from the 1920s to the outbreak of World War II, won several world championships in the 1950s, took its last grand prix victory in 1969 and its final TT successes in 1973 and ’92. Even in the company’s most recent and troubling guise, Norton continued to go racing.

Through all these ups and downs, Norton enjoyed its greatest days either side of WWII. During this period, the company’s stark and hugely effective single-cylinder racers were the dominant force wherever they went, from British short circuits to the Isle of Man and over the English Channel to the Continental Circus.

The overhead-cam single was designed by Walter Moore, who joined Norton in 1924 intending to return the company to its former glories following a lull in results. Moore was pragmatic and hands-on. His first task was to fix a rear-brake problem with the existing Model 18 overhead-valve racer, so he bought a job lot of Ford Model T brake drums and modified them to suit.

Moore wanted to learn how engines behaved during races, so he became a sidecar passenger. Paired with Brooklands regular George Tucker, he won the 1924 three-wheeler TT. The engine that Moore designed – with an iron cylinder and head, overhead cam, bevel-driven valves and Sturmey-Archer three-speed gearbox – won the Senior TT first time out in 1927.

Two years later, Moore’s engine, which was fast but noisy (riders called it the ‘clanker’) and prone to overheating, was redrawn to great effect. Between 1931-69 Norton 500cc and 350cc singles won 28 TTs, 41 world championship grands prix and countless internationals, defeating supercharged BMW twins and four-cylinder Gileras and MV Agustas along the way. That’s four decades at the top – no other machine has dominated the racing consciousness for so long.

Geoff Duke won world championships on Norton singles, Mike Hailwood, Phil Read and Stanley Woods won TTs on the machines, and Achille Varzi, Tazio Nuvolari and Piero Taruffi won continental races with them before moving into car racing.

John Surtees and his Norton Manx in 1955. He made his name on this bike and later that year joined MV Agusta

During the interwar years, British brands enjoyed an important development advantage over foreign rivals. Brooklands and the Isle of Man TT course were effectively open-air engine and chassis dynos, allowing British engineers to learn more about going fast than their European rivals.

Bikes were developed at Brooklands, raced at the TT and then transformed into production models. Norton was so aware of the importance of Brooklands that it established a race shop at the track, 125 miles from the factory in Bracebridge Street, Birmingham.

Hiring the best riders was also important, and their services weren’t always acquired through conventional means. In 1923, Norton team manager Don ‘Wizard’ O’Donovan was on the lookout for a new rider. He found him while driving to the shops in Weybridge, just down the road from Brooklands.

As O’Donovan turned a corner in his Morris Cowley, he came face to face with a wild young motorcyclist, slewing his Douglas motorcycle across the road, with a package of meat strapped to its rear. After a few enquiries he hired the butcher’s boy, Bert Denly, who went on to take countless race victories and records for Norton.

During the 1930s, Norton came to utterly dominate the Isle of Man TT. But by the outbreak of war, there was little doubt that the single’s day was over: BMW’s supercharged boxer twin had won the 1939 Senior TT, and Gilera’s supercharged straight-four won the ’39 500cc European Championship.

Coincidentally the devastation of WWII delayed the demise of Norton’s naturally aspirated single. Grand prix rules were rewritten to adapt to the circumstances of a peaceful, but shattered, Europe. Supercharging was outlawed, and machines were required to use low-grade pool petrol. Both these changes hurt the European manufacturers more than Norton.

No one was happy about detuning their engines for the 72-octane fuel, including Norton team manager and chief development engineer Joe Craig. But Craig was able to manage the situation better than his rivals.

While Gilera grappled with its straight- four, now without blower, Craig concentrated on eking more and more power out of his ancient but well-established engine.

“With over 30 years of experience, Joe’s practical knowledge gave him the ability to read combustion chamber colours to the nth-degree,” recalled Norton factory rider Rod Coleman. “Consequently, his engines always ran at absolute maximum compression ratio, fed with the leanest mixture. This enabled Norton to keep ahead of the multi-cylinder opposition for much longer than should have been possible.

“Plus, of course, the very simple design, which allowed the cam box and cylinder head to be removed, and the combustion chamber studied by the side of the road. Sometimes during practice, the Norton team located itself around the back of the circuit, where a mechanic would remove the cylinder head, Craig would inspect it, then ask the mechanic to add or remove a cylinder base shim. The fours required workshop facilities to do this, so they were run well on the conservative side of compression ratio because the fuel octane supplied at each circuit varied so much.”

Craig, who rode for Norton in the 1920s and masterminded its successes from the ’30s to the ’50s, was a gruff, no-nonsense character from Ballymena in Northern Ireland.

“Joe knew exactly what he wanted,” said Tim Hunt, who did the Junior/Senior TT double for Norton in 1931. “I remember him complaining to the Lucas rep about their magnetos. He said there were three good things about Lucas magnetos: the box they came in, the paper the package was wrapped in, and the string it was tied with.”

Although Craig’s speciality was painstaking trial-and-error development rather than design, he always made use of the latest thinking to keep Norton competitive. He gradually widened the bore and shortened the stroke of the 500 and 350 to use larger valves and more revs. He also developed a DOHC head, filled valves with metallic sodium for improved cooling and replaced internal flywheels with external flywheels to reduce oil drag and save weight.

However, logical and patient engine development wouldn’t keep Gilera at bay forever. What Craig needed was a scientist. He found him in Leo Kuzmicki, a Polish engineer with a keen understanding of flame propagation in combustion chambers.

Kuzmicki endured a traumatic war. After joining the Polish Air Force, he was captured by the Russians and spent several years in an NKVD labour camp in Uzbekistan. Kuzmicki would later make his way to Britain via Bombay. He spent the final years of the war fettling Hurricane fighters and Sterling, Wellington and Lancaster bombers. After joining Norton in 1949 – the inaugural year of the world championships – he worked his magic on the 500 and 350, increasing horsepower by 30 per cent.

Two years later Craig, Kuzmicki and two other forces of nature took Norton to the pinnacle of the sport: the 500cc world title.

At the end of 1949, Norton had signed 26-year-old rider Geoff Duke. The Lancashire youngster’s skills were already supreme, so he should have won the 500cc riders’ world title at his first attempt the following summer. Only two tyre failures, at Spa-Francorchamps and Assen, stopped him.

Duke gives the Kuzmicki/ McCandless 500 its debut at Blandford in the spring of 1950

In 1951, Norton did beat Gilera’s mighty four, thanks to Duke’s talent, Craig and Kuzmicki’s brilliance and the genius of Rex McCandless, another racer turned engineer from Northern Ireland. In the ’40s, McCandless developed the first fully- sprung motorcycle chassis. He tried to sell his idea to Triumph, but while wining and dining a Triumph executive he was told the company couldn’t possibly use a “foreign” invention in its motorcycles, so McCandless upended the table in the executive’s face. Next, he went knocking at Norton’s door.

Duke tried McCandless’s chassis and announced that it “set an entirely new standard in road-holding”. He was right. The all-welded frame with telescopic forks and twin hydraulic shock absorbers became the basis for motorcycle chassis design for the next three decades.

The 1951 grand prix season featured the struggle between Norton and Gilera, which was very lopsided. The British single made 40 horsepower, 25 per cent less than the Italian four. Duke remembers Gilera’s Umberto Masetti having so much power to spare that he could “pull alongside, sitting upright, while I almost had my head under the handlebars”.

On the other hand, Norton’s new chassis allowed Duke to keep his chin on the fuel tank and the throttle against the stop, whereas Masetti had to roll the throttle to maintain control of his bucking machine.

Britain’s greatest racing marque claimed motorcycling’s greatest prize thanks in part to the input of three ‘foreigners’: Craig, Kuzmicki and McCandless. This was nothing new. When Norton won the twin-cylinder class at the 1907 TT, it used a French Peugeot engine, but James Lansdowne Norton erased the FP logo (for Frères Peugeot) from the crankcases to disguise its origins.

Norton’s 1951 successes, the riders and constructors titles in the 500cc and 350cc world titles, were at the same time the company’s finest hour and the beginning of the end. Everyone knew that Norton’s reign would cease as soon as Gilera created its own McCandless-type chassis.

A unique photo: Joe Craig, MD Gilbert Smith, 1952 Senior TT winner Reg Armstrong, engine tuner Leo Kuzmicki and chassis designer Rex McCandless

Norton managing director Gilbert Smith knew he needed a four, so he entrusted car company BRM with design and development. Duke was hugely keen on the new engine because by 1952 Gilera had indeed equipped its 500 four with a fully-sprung chassis, which forced the reigning champion to take ever- greater risks to stay in the hunt.

At the end of 1952, Smith asked his star rider to extend his contract, but Duke said he would only stay if he could race the BRM four. “Gilbert admitted there was no possibility of the four being ready to race in 1953,” Duke wrote in his autobiography In Pursuit of Perfection. “I also told him that my desperate attempts to beat the Gilera fours were partly responsible for several crashes I’d had. Smith refused to accept this and suggested that my problem stemmed more from having attended too many dinners and dances.”

Norton’s reign as a grand prix great was over. Duke went off in a huff to ride for Gilera, Norton didn’t have the budget to develop the BRM engine, Gilera assumed domination of the world championship and finally Norton withdrew its factory team at the end of 1954. That wasn’t quite the end of Norton as a grand prix force, of a kind.

The company continued to sell its 350cc and 500cc Manx privateer machines, which remained the backbone of world championship grids into the 1960s. For example, 55 of the 81 starters in the 1960 Senior TT rode Manx 500s, and 57 of the 97 starters in that year’s Junior TT rode Manx 350s. The standard stable for a Continental Circus rider was a 500, and 350 Manx bought each spring from Bracebridge Street, for £350 apiece. An extra £5 bought blueprinting and a bench test.

The aim of these privateers wasn’t so much to conquer the world, but rather to earn a crust by working their way around Europe, competing at grands prix and non-championship events, surviving on the meagre start and prize money.

Norton’s final GP victory went to British privateer Godfrey Nash at the season-ending 1969 Adriatic GP in Yugoslavia, where the dominant MV Agusta factory was a no-show, having already secured the world title.

Norton did win one more world crown, or at least part of a Norton engine did. In the early ’50s, British businessman Tony Vandervell vowed to beat Ferrari and Maserati in Formula 1, so he hired Kuzmicki to develop a straight-four engine for his Vanwall car, using four over-bored Norton top ends attached to a Rolls-Royce B40 crankcase, more usually found in Daimler Ferret armoured cars. The 2489cc Vanwall won its first F1 race in 1957, with Stirling Moss driving. The next summer Moss missed out on the drivers’ title by one point to Ferrari’s Mike Hawthorn, but Vanwall won the constructors’ title over Ferrari.

From the 1950s, Norton’s fortunes were dictated by the ructions that tore through much of British industry. The struggling brand was sold to Associated Motor Cycles in 1952, and when AMC collapsed in 1966, it was sold to Manganese Bronze Holdings, run by former racing driver Dennis Poore.

In 1970, Poore sent Norton racing again, with a Formula 750 machine powered by a twin-cylinder Commando road-bike engine and bankrolled by Imperial Tobacco.

The key player in the first John Player Norton project was brilliant rider/engineer Peter Williams, son of AJS engineer Jack Williams. He would build a stainless-steel monocoque for the F750 machine, which he rode to victory in the 1973 F750 TT, breaking the outright Isle of Man lap record.

Poore’s plans for Norton centred around an all-new water-cooled Cosworth engine, basically two cylinders off a DFV F1 unit, which would power Norton’s F750 machine and a range of sports bikes. But the engine was too big and too heavy for motorcycles and ran poorly.

At the same time things went from bad to worse for the business. Mounting losses, labour problems and a new generation of high-performance superbikes from Japan finished the company off in 1976.

For a while, at least. Poore and a skeleton staff continued working on a new rotary engine, designed to power motorcycles, drones and boats. However, Poore fell terminally ill with cancer, and Manganese Bronze sold the company in 1987. South African-born financier Philippe Le Roux, who was keen on the Norton name and the rotary project, then became the new owner.

When development engineer Brian Crighton convinced Le Roux that the twin- rotor unit would make a great racing engine, he was allowed to create a race bike, working evenings in the kitchen of the factory caretaker’s house. The rotary quickly became a huge force in racing, encouraging Imperial Tobacco to open its chequebook once again.

Brian Crighton working on his rotary racer in the kitchen of the factory caretaker’s house

By 1989, Crighton had transformed the 92-horsepower road engine into a howling 148bhp race engine that won the 1989 British TT F1 title. British fans flocked to the circuits to watch the all-British RCW588 – painted in the iconic black-and-gold JPS colours – defeat Japan’s best superbikes.

In 1992, the rotary scored its greatest success when Steve Hislop won the Senior TT. This was a historic achievement against enormous odds. Team manager Barry Symmons was not only running a race team, he also had to deal with bailiffs who were sneaking into the race shop to settle debts, which were once again piling up. “One day we arrived to find a bailiff’s truck loading up all of the mechanics’ toolboxes,” Symmons recalled. “Another time they wandered off with the CNC machine.”

Neither was the rotary an easy machine to run on the racetrack. The engine was fragile, thirsty and produced power in such a way that the chassis struggled to keep up. Hislop, who lost his life in a helicopter crash in 2003, had to wrestle the machine to victory.

“I was riding the bike beyond its limits – I was totally out of control at 180mph,” he wrote in his autobiography Hizzy. “At that speed, instinct takes over, and for the first time in my life, I started thinking that maybe victory wasn’t as important as living. But that soon passed, and I got my head down again.”

In early 1993, the bailiffs closed in for the kill. Norton had once again come to the end of the road.

But not for the last time…

Kenny Dreer’s ownership of Norton

His ownership of Norton lasted little more than a year.

American Kenny Dreer’s stewardship was promising. He designed a new air 961cc Commando, aimed at the growing retro market, but the bike was never made. In 2008 Dreer sold his interest to British businessman Stuart Garner, who developed and produced the 961 at his site at Donington Park.

Garner (right) wanted to go racing, so he signed multiple TT winner Michael Dunlop for the 2009 TT aboard an updated rotary. The NRV588 had so many problems that Dunlop didn’t complete a practice lap.

The rotary was replaced by a new machine powered by a revised Aprilia RSV4 superbike engine, which lapped the TT course at over 130mph, but never challenged for victory. The V4 engine and a new road/race 650cc parallel twin were more recently manufactured by Chinese company Zongshen.

During this period, Garner attracted government interest in his venture, including a £4m grant and the underwriting of a £7.5m bank loan.

However, in January 2020, Norton collapsed into administration, amid accusations of fraud.

Garner is being investigated regarding the misappropriation of £14m invested in three pension funds he had established. More than 200 people are expected to lose their life savings as a result.

In April, Indian firm TVS Motorcycles purchased Norton, which had debts of around £30m, for £16m. TVS produces around three million small- capacity units annually, including BMW-branded motorcycles. Will TVS continue Norton’s racing activities?